Adapted from a theory proposed in Isabelle Graw’s treatise on medium, The Love of Painting (2018), the collective title under which these works are hung misquotes the modernist emergence of the “damaged subject,” as Graw writes, an entity which appears to have lost control of itself, and yet whose aliveness is hinted at through painterly gestures.

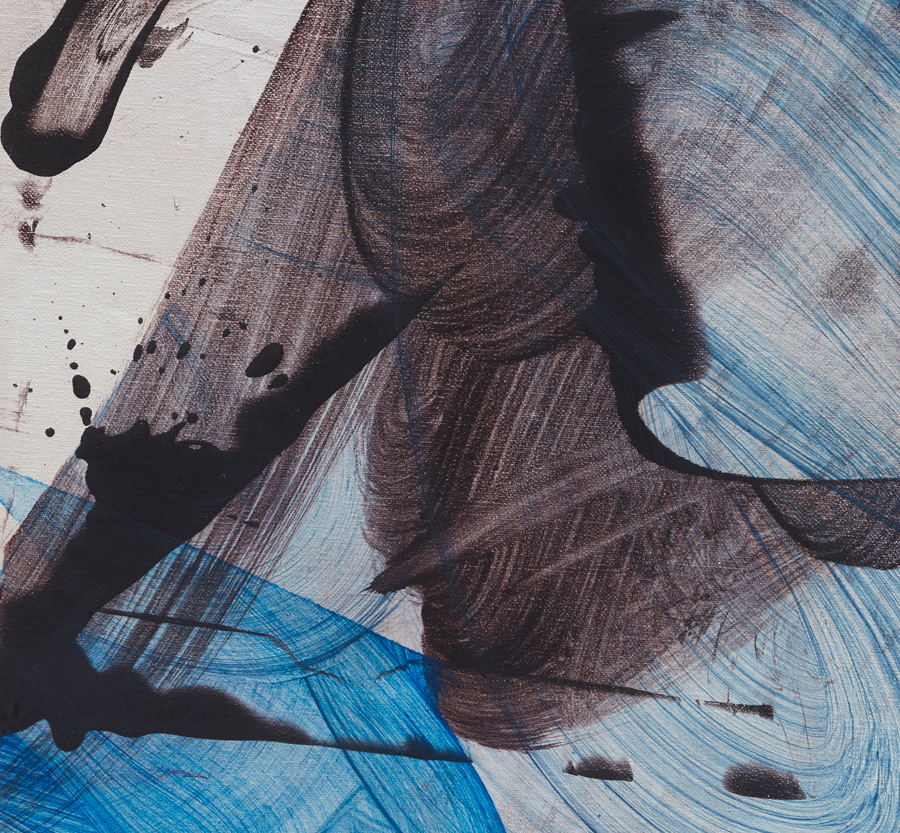

Certainly, Dennison’s well-rehearsed canon of brushstrokes—squeegee tugs, rag smears, palette knife smudges, hog hair daubs, turpentine-wetted washes, wipes, pours, pools, and deletions—is suggestive of her presence, as if it has been imbued into the very fibers of the canvases. But there is a latent tension between the logic through which Dennison applies paint, and the motifs realized by these applications.

Representational subversions abound in this new suite of works, which builds out the artist’s style to embrace more preternatural hues, such as chartreuse, which appears in varyingly transparent licks and splatters in Burnt Out! Green 1, 2, and 3 (all works 2024). The insistence of the vibrant, monochromatic swathes backed onto lightbox-like, neutralizing gesso calls into question what can be visually compelling, what can be beautiful, and what can be considered a “fast image.”

Albeit more muted in palette, Tilted Painting, and the abstraction, No one understands me and no one understand my art, further invoke the “fast image” as one equally related to the rate of its production, as well as how quickly it can be consumed by the eye. Also relevant is the speed at which said eye can (fail to) recognize the patterns, quotations, and excerpts alluded to in these works, putting forward the notion of painterly gestures as potential readymades.

The semantics of Dennison’s language of abstraction are directly informed by this multidimensional relationship to fastness. Economies of attention become relevant toward interpreting these paintings which disturb the medium’s art historical conventions. Some through trompe l’oeil effect, seeming as if they have been stretched in improper orientations, spilling and spinning out of the bounds of their canvases and thus disordering visual hierarchies; others appearing as parenthetical attitudes, being assembled of multiple incongruent panels.

This phenomenon is exemplified by the bisecting E-comm paintings, which depict the appropriated silhouettes of ubiquitous fashion garments in thick, swirling impasto against blank, flat backgrounds comparable to the screens we scroll absent-mindedly. Three senses—of the interruption of the gesture of scrolling, of automatic contemplation, and of the further possibility of the digital image as both signifier and readymade—are invoked by these compositions.

The banal effect of these commodities as recognizable is complementary to the impact of viewing the Jacob’s Ladder Flowers paintings—arguably the hallmark of the artist’s recent practice—in which she renders the abstracted anatomy of the eponymous flower. That our evolutionary instinct to recognize flowers because they turn into food extends into an ability to identify commercial objects at a glance is the punchline of Dennison’s understated humor, a comedy revolving around the pleasures of recognition.