Tara Downs is delighted to present Relics from an imaginary friend, Kelly Tissot’s first exhibition at the gallery, and the France-born, Switzerland-based artist’s solo debut in the US. Encompassing large, sculptural, black and white photographic works, and at times site-specific three-dimensional constructions, Tissot (b. 1995) uses the material landscape of one of France's most remote areas as a matrix for visual investigation. Regularly returning to this region in the east of the country where she originates, the artist immerses herself into a subcultural environment in order to capture fragmented signs of life on the margins.

From this peripheral perspective on the rural, Tissot sheds a different light on idyllic representations of the countryside. Cold, imposing, and hieratic, her works depict a world that lies at the opposite end of pastoral stereotypes: life is haunted and damaged; all is ruled by silence and power. Within her photographs, Tissot faces a kind of spectral violence, one of desolation. Her almost clinical approach to these remains of human activities – while humans themselves seem to be absent from the pictures – spurs a form of tactile attraction. Their austere beauty, their sensual attention to surfaces, and the material details which are made so available to the eye, all suggest a form of affection, of being touched by these broken scenes. And, while they are touching us, they also, in return, make us want to touch them, these apparitions, these flickering ghosts.

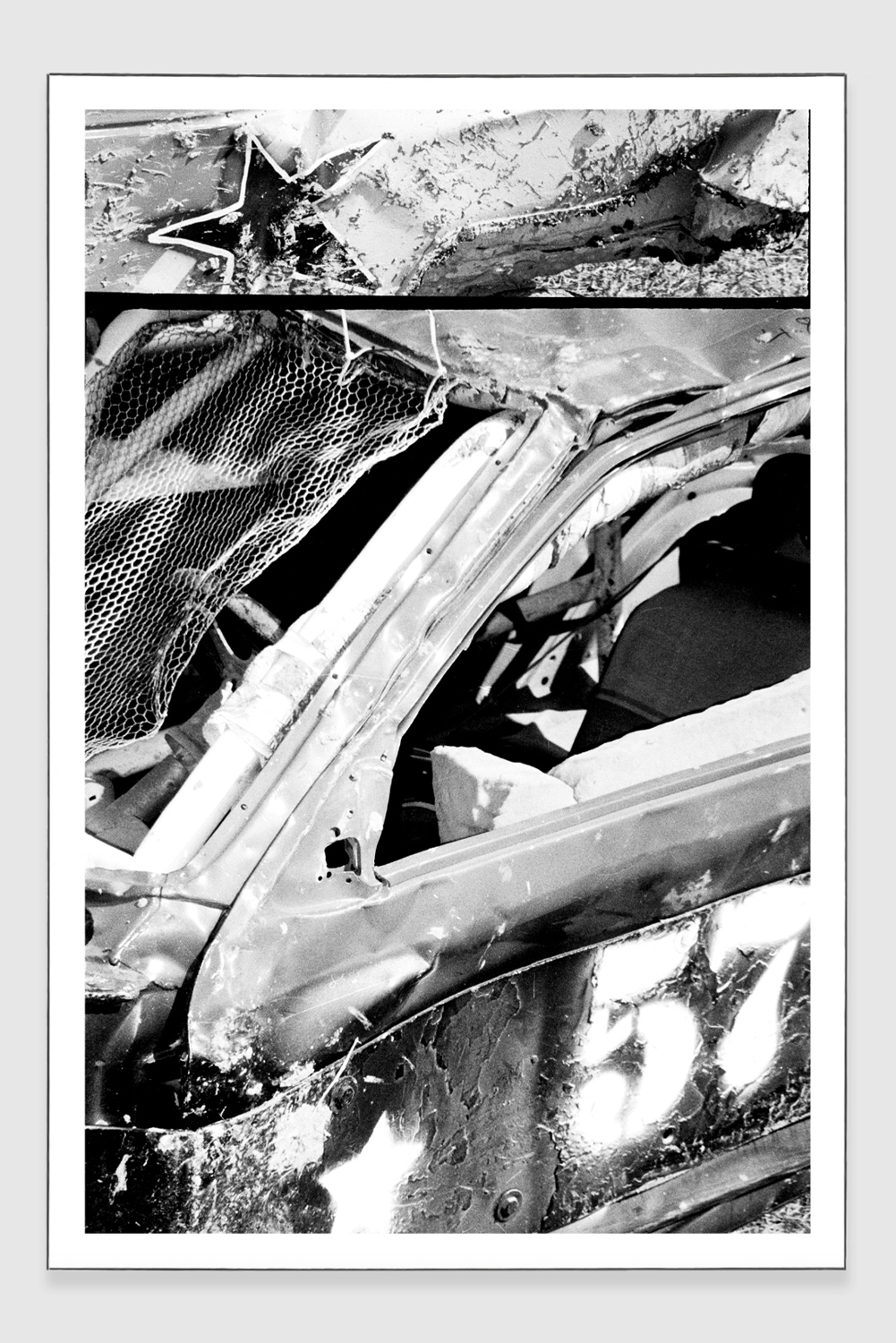

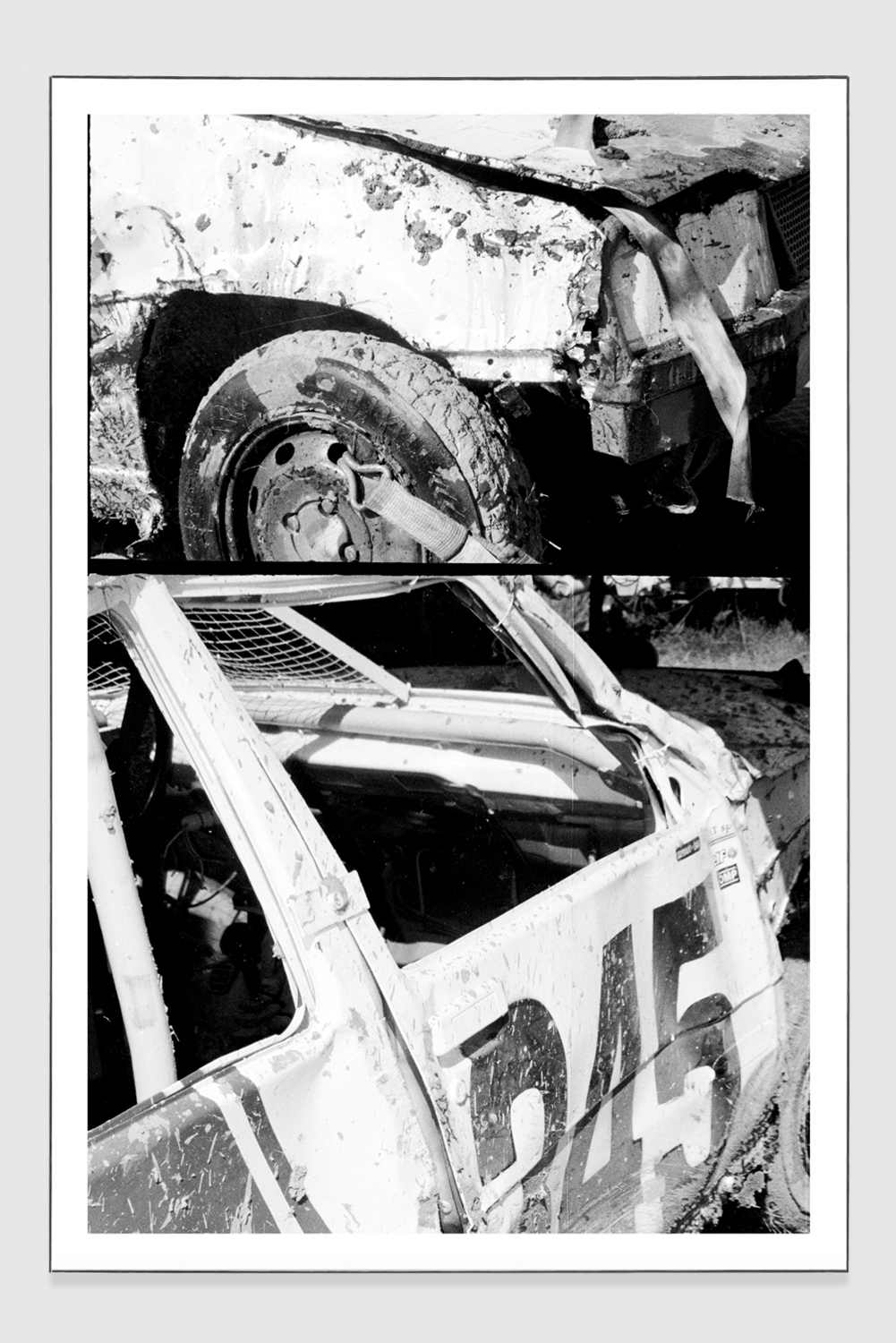

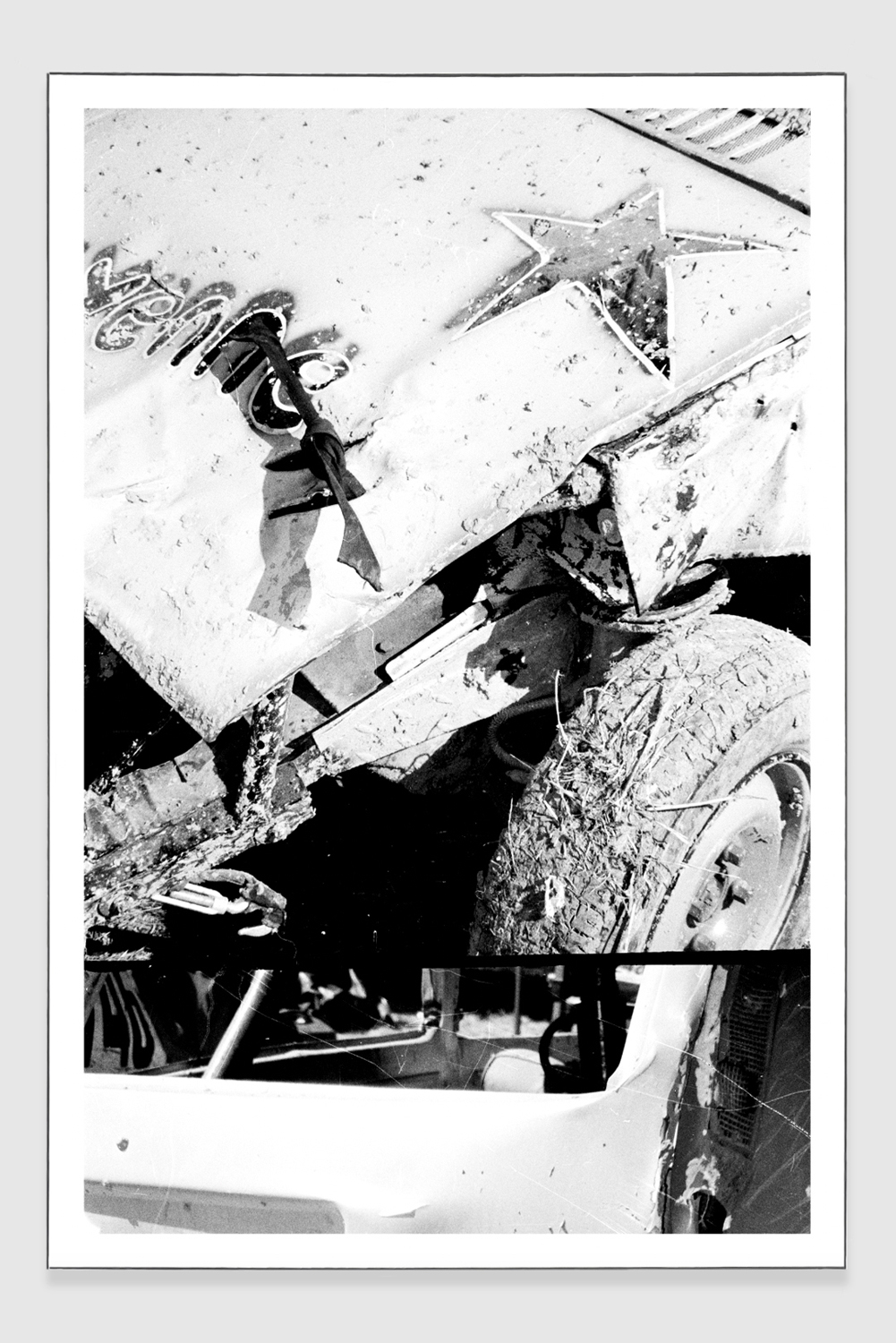

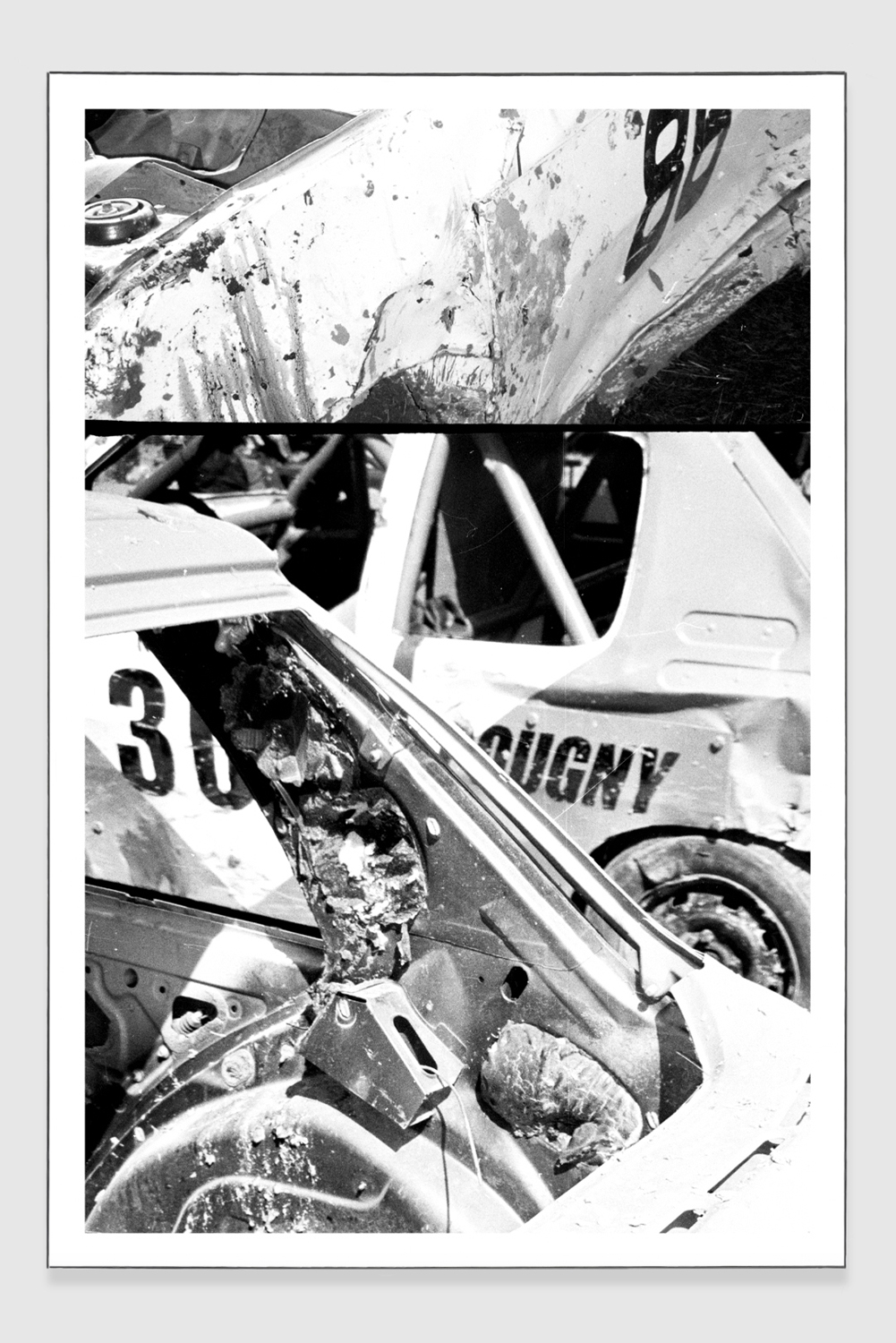

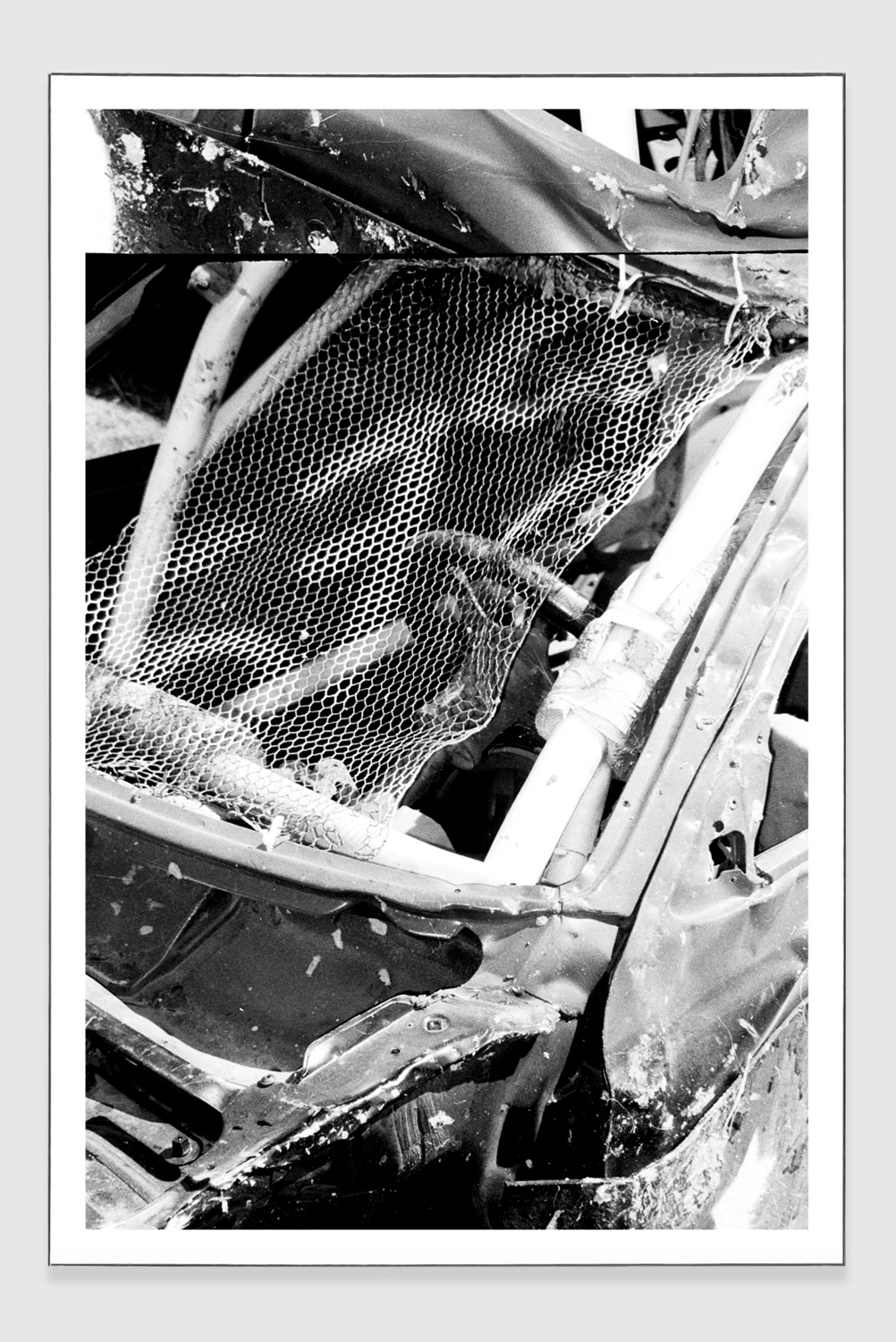

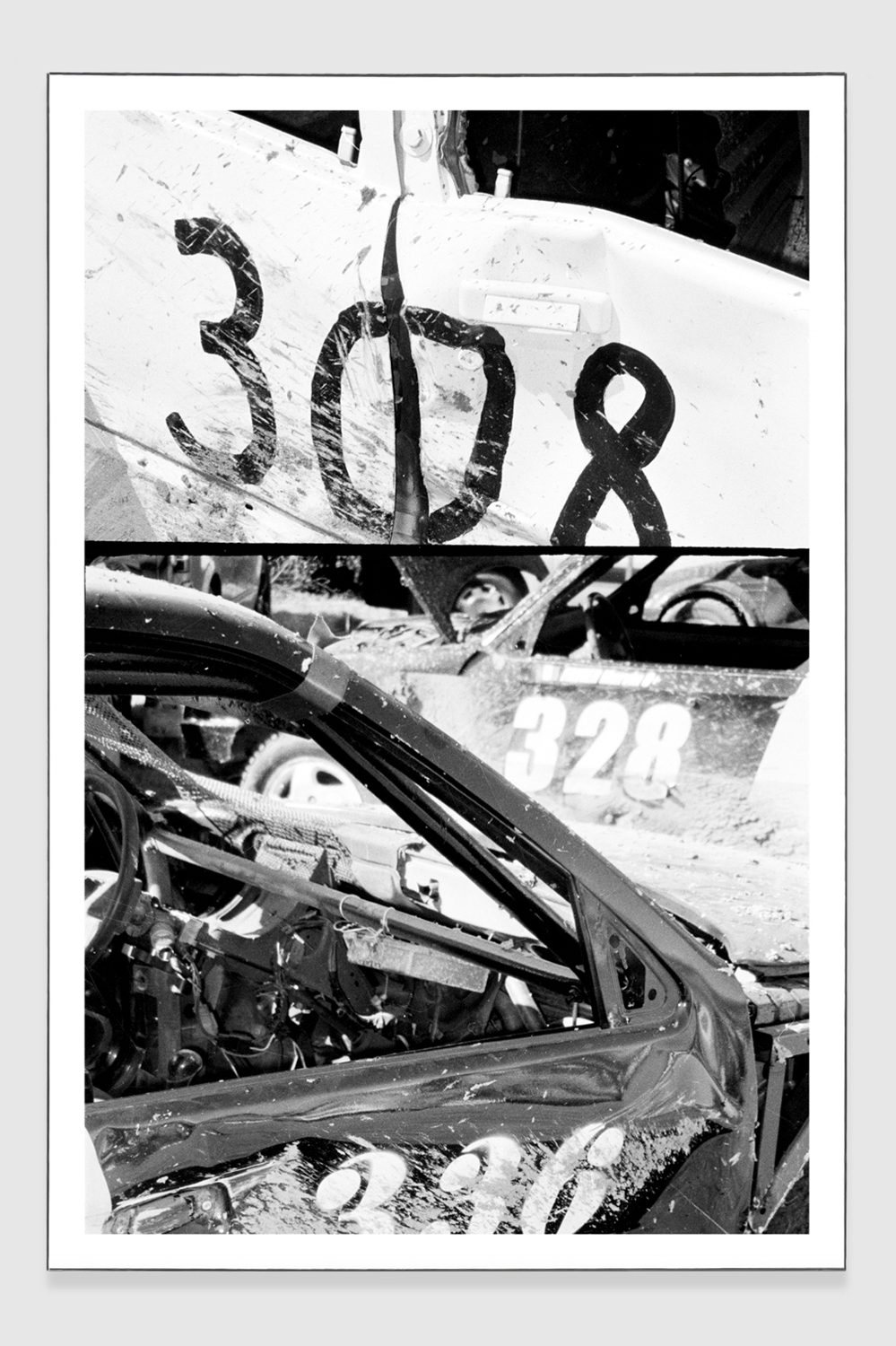

Youth / Bows, bones and ribbons (2024) is Tissot's most recent series of works. It is composed of six large photographic prints on canvas, framed with raw oiled steel. Each work is based on a montage of close-up shots depicting wrecked cars, crumpled metal parts, and destroyed wheels. Shot in black and white, these pictures are a continuation of the artist's longstanding interest in stock car races. Since 2016, she has been documenting an illegal competition that takes place every summer in France, in the same area that has been the focus of previous series. Tissot uses an analog camera, which allows her to focus on and reveal a myriad of sculptural details. The pictures are then digitalized, after which the artist zooms, edits, and mounts the photographs, thus composing these mechanical-archaeological excavations. Glass windows and windshields are removed, cabins are padded, vehicles are reduced to minimal apparatuses made to be crashed. Tissot documents what remains after the race: folded metal sheets, pierced car hoods, all of the wreckage exhibits a series of human destructive production, a kind of negative cooperation between the drivers and their ruined equipment.

The metal relics Tissot depicts are the result of a car contest whose aim is not to be the fastest, but the collective and progressive destruction of all cars involved. Various teams throw their cars onto the track to generate collisions, to execute a series of imposed crash ‘figures’, until the last remaining and functioning machines finish the race — the only rule being not to drive against the flow. The participants begin by preparing their vehicles a year in advance, finding second-hand stock cars that they modify, adding fake engines, tuning their pipes, and painting numbers and names on the vehicles as gestures to family, lovers or friends. The gathering itself looks like an apocalyptic live show, where the sound of screaming engines roars, and the smell of fuel, oil and dust, along with the stress, fright and adrenaline, alters one's perception and turns the automotive sport into a kind of multi-sensorial destructive spectacle.

Looking closely at the artist’s images, one can observe the delicacy of some steel parts that have been stitched, and how others have been strangely replaced or carefully repaired, resulting in the metal looking like bruised and creased skin. Her close-up photographs also function by allowing the viewer to visually scan the blown-up debris. The camera approaches textures and turns around the cars in a sort of cinematic traveling, objectively observing the material layers revealed by the collisions — it smoothly approaches, like an animal smelling something, prey, a menace within the hybrid compositions, the damaged cyborg apparatuses. The artist doesn't photograph the race itself, which we can only imagine. The montage of pictures within the frames plays with cutting and repetition, which induces movement through Tissot's serial documentation and reinforces the mechanical facets of her subject matter. This evokes the circular form of the track and the cyclical component of this annual ritual, of this destroying feast.

The fact that Tissot shows only fragments, cropped shots that immerse the viewer in their scenery and generate many ellipses — camera zooms, cuts in the images, and the black lines that separate them — implies everything that remains outside of the rigid metal frames and invites us to picture the chaos, noise, and feelings of this carnivalesque race. The artist doesn't photograph the event itself but its aftermath, what remains. Additionally, the analog camera allows this particular sense of time because Tissot doesn't totally control what the picture will look like. The ellipses are also places that refer to missing digital pictures between the works, moments when the artist is operating blindly, when it's possible to close one's eyes to picture the experience instead of representing it. Contrary to Andy Warhol's Death & Disaster series, Tissot doesn't propose a distant meditation on death and the fading effect the media has on an image's impact. Instead, her camera brings back these quiet, living dead things; perhaps Ballardian entities, the half-bodies and half-machines of scorched cars with their wounded and sensual metallic beings, whose owners also exhibit after the competitions, displaying them as ready-made sculptures around the racetrack and in their gardens.

The black and white photography creates a certain distance, neutralizing the potential aestheticization of the masculine world of mechanics à la John Chamberlain. The high contrast and the way the images interact in pairs and as a montage suggest they are cosmically drawn to each other's weight within the gallery space, forming a conceptual composition akin to a constellation. Furthermore, stock car races have obscure origins: in the US, they emerged in response to Prohibition in the 1920s, when the production of homebrewed liquor (moonshine) began. Moonshine runners transported their illegal goods at night under the light of the moon in modified cars with powerful engines that outpaced the police. Over time, these runners organized their own racing competitions. While the dramaturgy of these races continuously evolved, organizers eventually discovered that the grand finale—where participants were invited to destroy each other's vehicles—attracted more spectators than the races themselves. This marked the inception of demolition car competitions, which became a distinct practice known for staging "bangers" or "big bangers".

Within the violent, macabre, and frightening atmosphere of these gatherings, perhaps resides a collective method of transfiguring and channeling the powers of the original explosion of particles. What if the relics of the stock car races that Tissot is examining are actually imbued with this primordial energy? A vibration, dangerous yet also a source of creation and transformation. This could be one reason why the artist was initially drawn to these "heavy metal" rituals: they echo the terrestrial manifestation of the destructive force from which we also originate.