A few words about the distinction between the tableau and the picture... The tableau is a form. When it assumes this form, the pictorial work – the picture – affirms its status as an autonomous image. The tableau is moveable. It is not fixed to one single place. It constitutes its own place.

– Jean Francois Chevrier, Inside the View: Tableau and Document, lecture.

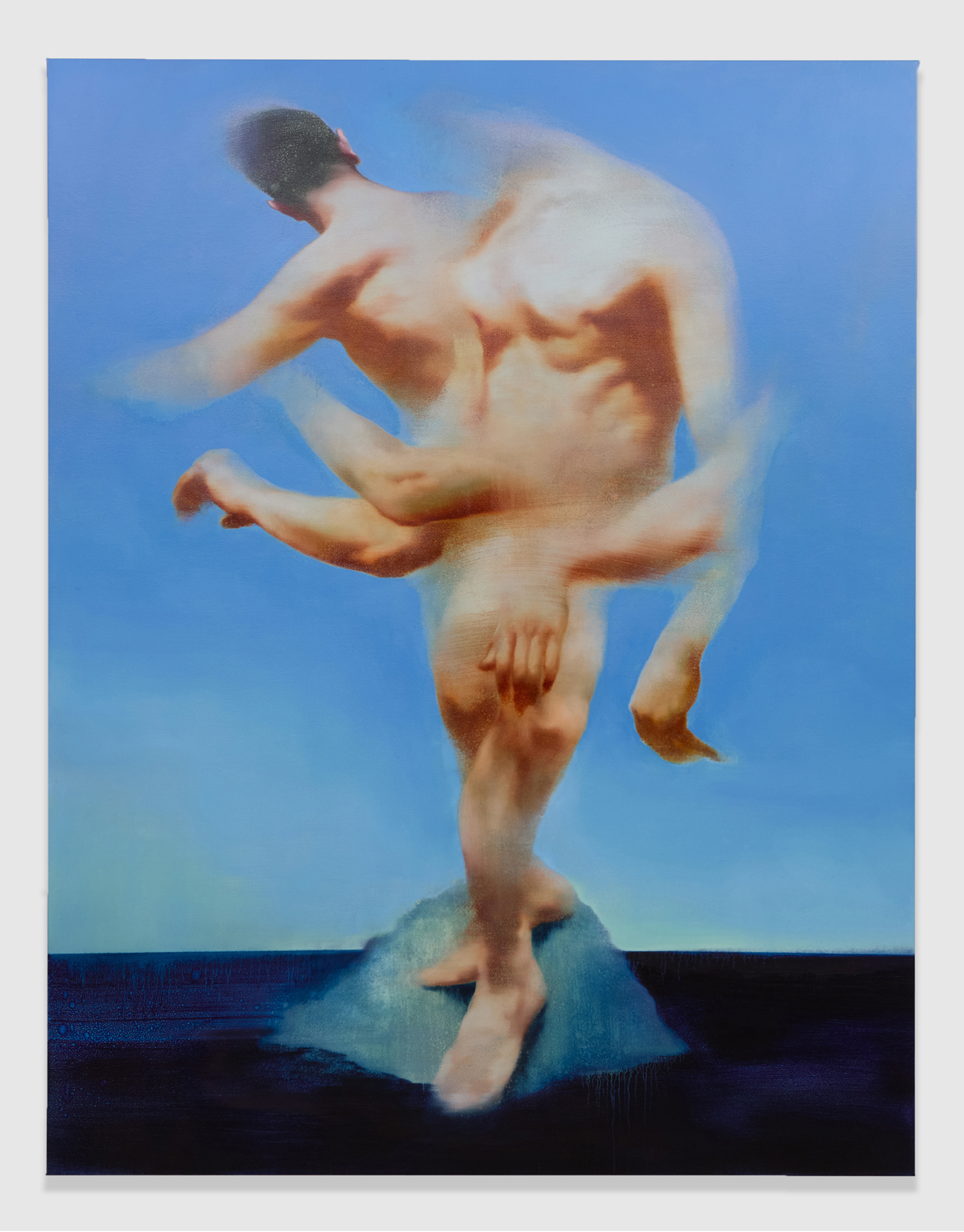

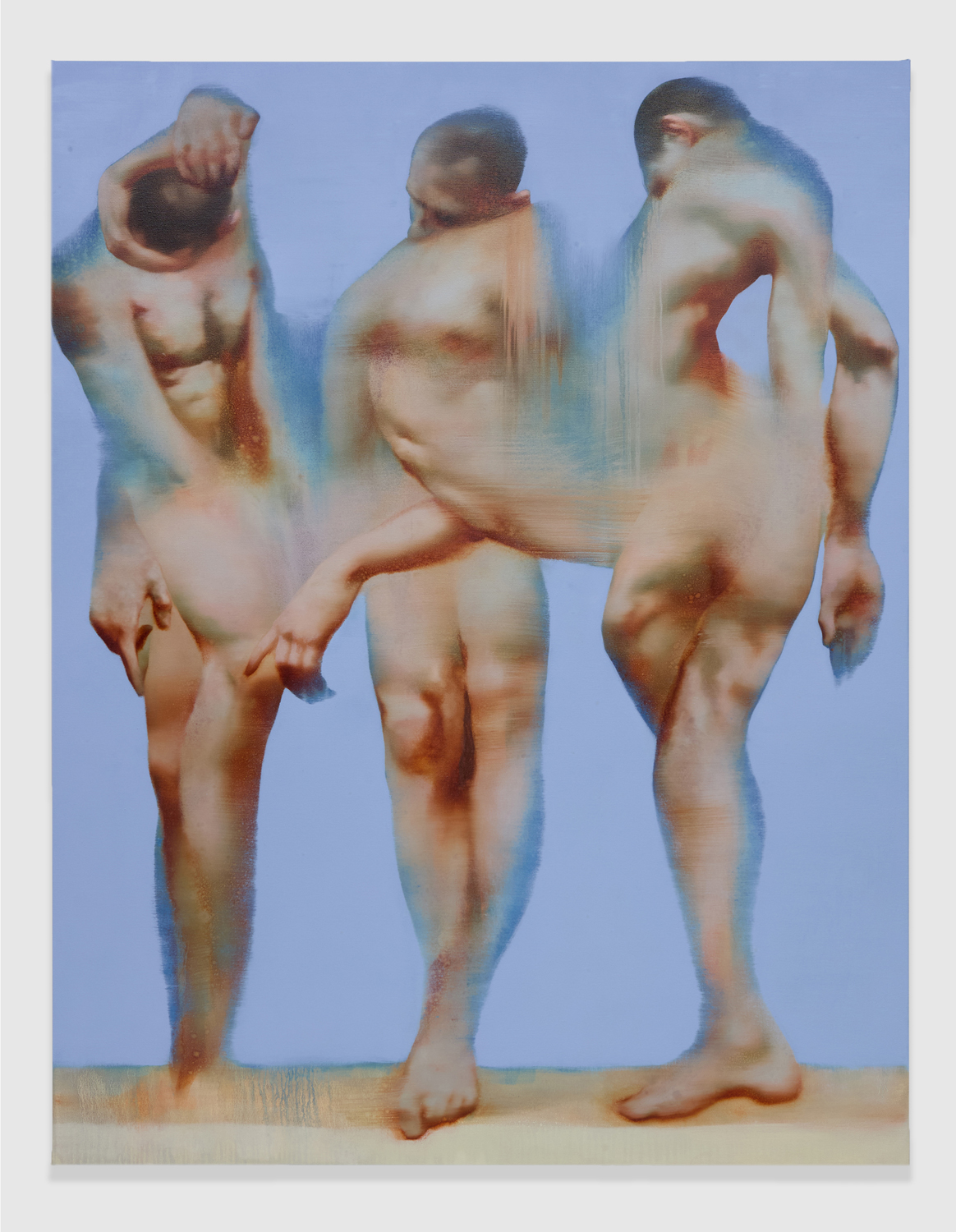

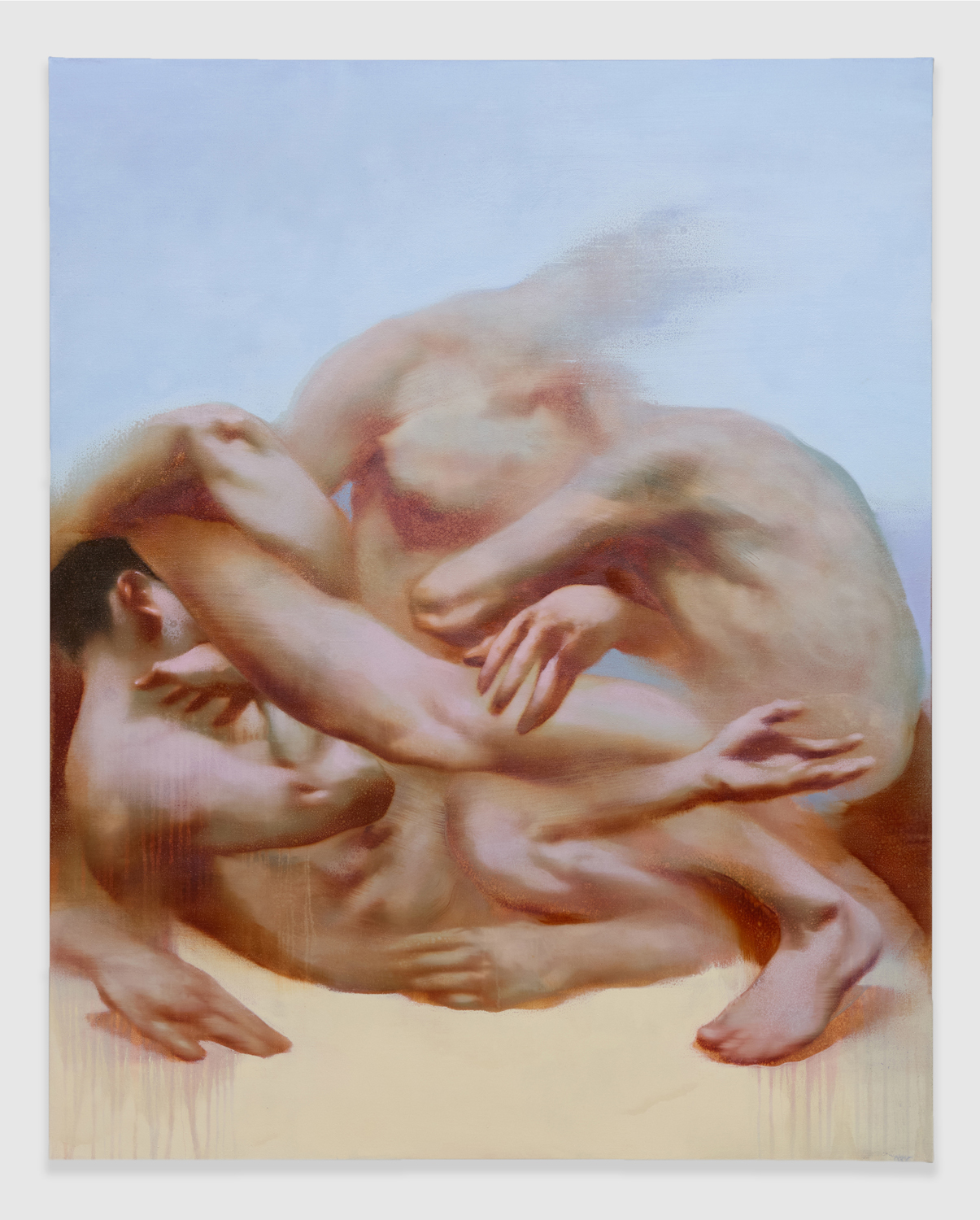

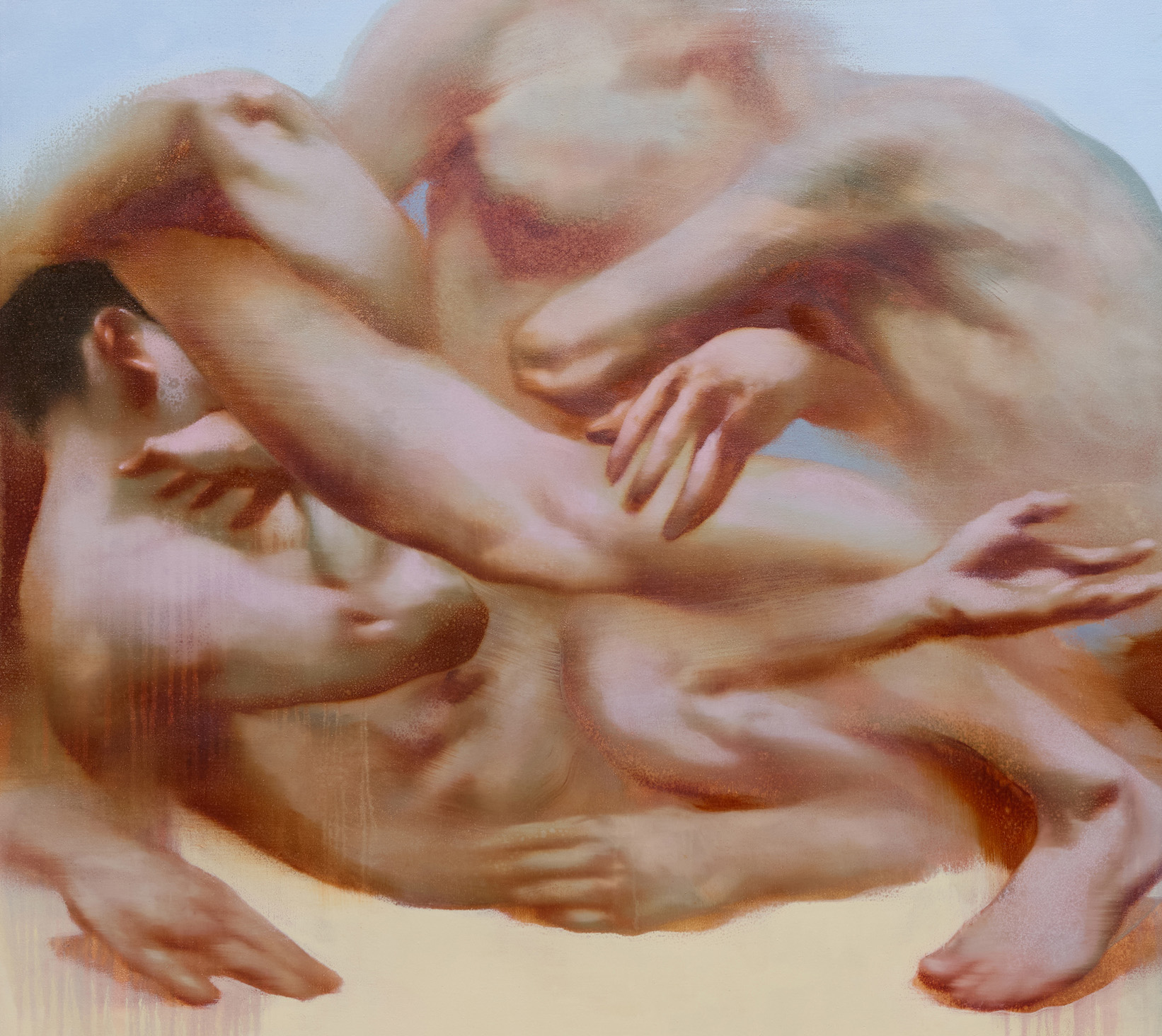

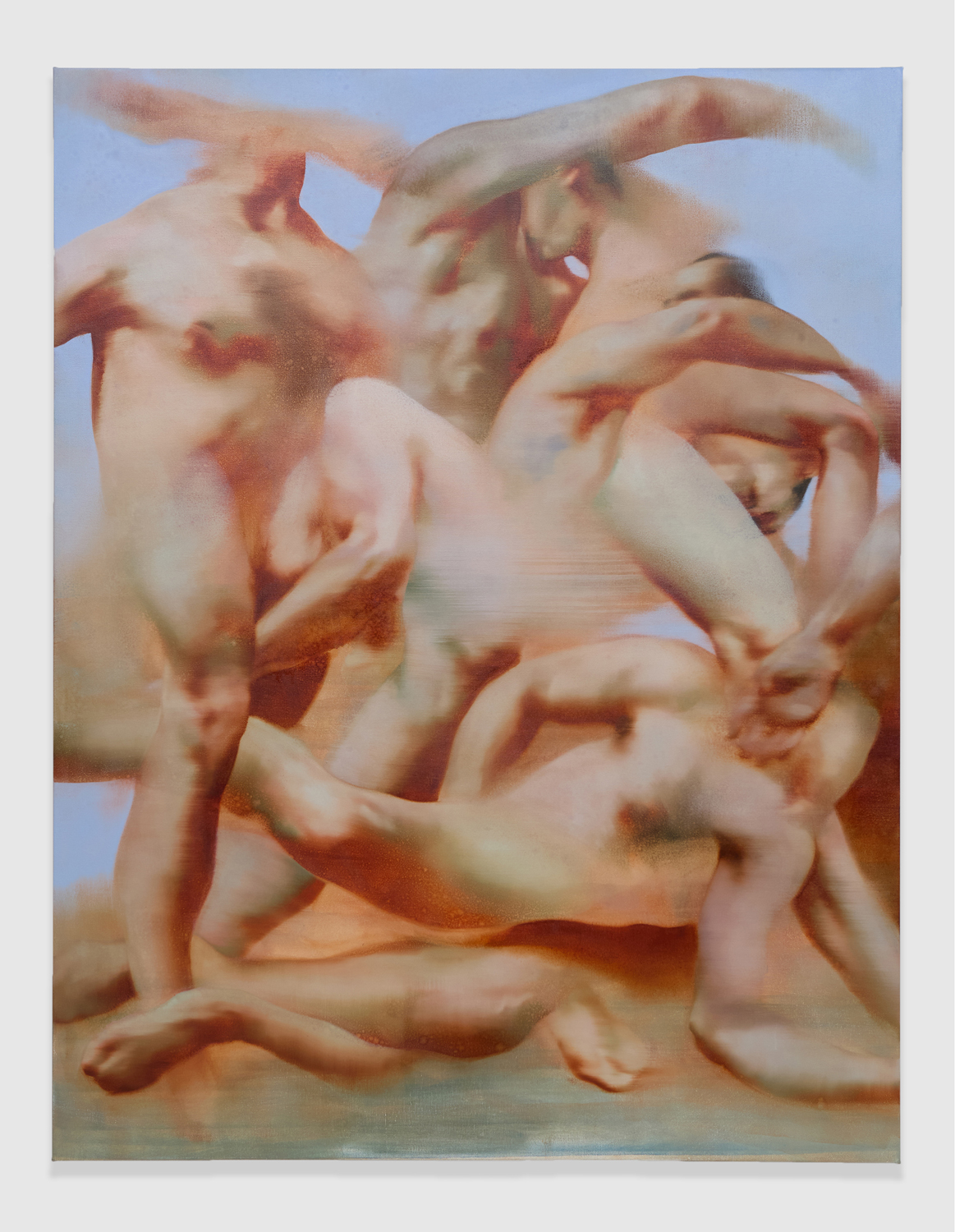

This exhibition both serves as an introduction for US audiences and deepens our understanding of Kostov’s recent paintings in oil, imposing works of energetic composition and virtuosic figuration. The many tangled bodies of these paintings jostle against one another, groping and clutching, and stay suspended in action, as in history painting, but remain autonomous from any tangible narrative, untethered to any grounding element that could lend itself to easy interpretation.

These works initially appear to emerge from an interstitial space between aggression and eroticism, the actual and the virtual, the historical and the present. They seem to draw upon an Old Masters understanding of the body, or suggest the bold palette of Florentine Quattrocento painting, but also might engage in a lineage of existentialist (dis)figuration after Francis Bacon, or more recent conversations surrounding the human figure and generative AI. In Perfect Strangers, 2024, for instance, the perplexing huddle of headless bodies – a menagerie limbs and torsos – is doubled by the vaporous setting, flat compartments of bright blue, dusty pink, or earthy green, all suggestive of a landscape, but one which never quite coheres into a readily legible context.

Yet the paintings on view also explicate a considered relationship to sculpture, one perhaps less apparent in the artist’s earlier oeuvre. Against the brilliantly- colored backdrops of these works, we begin to see the figures in high-relief, and begin to glean more clearly the artist’s process of composition-building. Kostov begins by effacing the canvas with organic blots of paint, formless planes of color that serve as the Rorschach test-like basis through which he builds his doubled- over compositions. It is tempting to ascertain, in this process of accretion, not only a correspondence to additive sculpture, but also a correlation to the procedures of memory. And, indeed, these works refer back to the artist’s personal history – moments and impressions accumulated among Kostov’s native Bulgaria and his home in the United Kingdom, as well as the United States. Yet, more often, they suggest a sort of dream logic rather than a documentary impulse, a reworking of the residue of memory until it no longer bears direct relation to lived experience.

The exhibition title itself, Between the five wells, elucidates this sort of positionality, referencing an actual, physical place meaningful to Kostov, while also evoking the disorienting sense of liminality, the “betweenness,” conjured by the works at hand. The art historian Jean Francois Chevrier’s understanding of the tableau – as a picture that insists upon its own contrivance, its own fabrication – may be pertinent here, to these works that always seem to emerge from a suspended sense of becoming. Or, alternatively, regarding the work of a very different artist, although perhaps a fellow traveler, Ambera Wellman, the curator Nicolas Bourriaud has said that Wellman, “does not represent bodies, but the circumstances of their disappearance into the fluidity of the world.” Against this notion, drawing ourselves somewhat closer, we might say that Kostov’s innumerable bodies perform something else, documenting the ways in which temporally-determined gestures, movements, dispositions engendered by the human form assert themselves visually and, in fact, construct the world.