Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, 人間 Live, 2024. Oil on canvas, 47 1/4 × 94 1/2 in / 120 × 240 cm

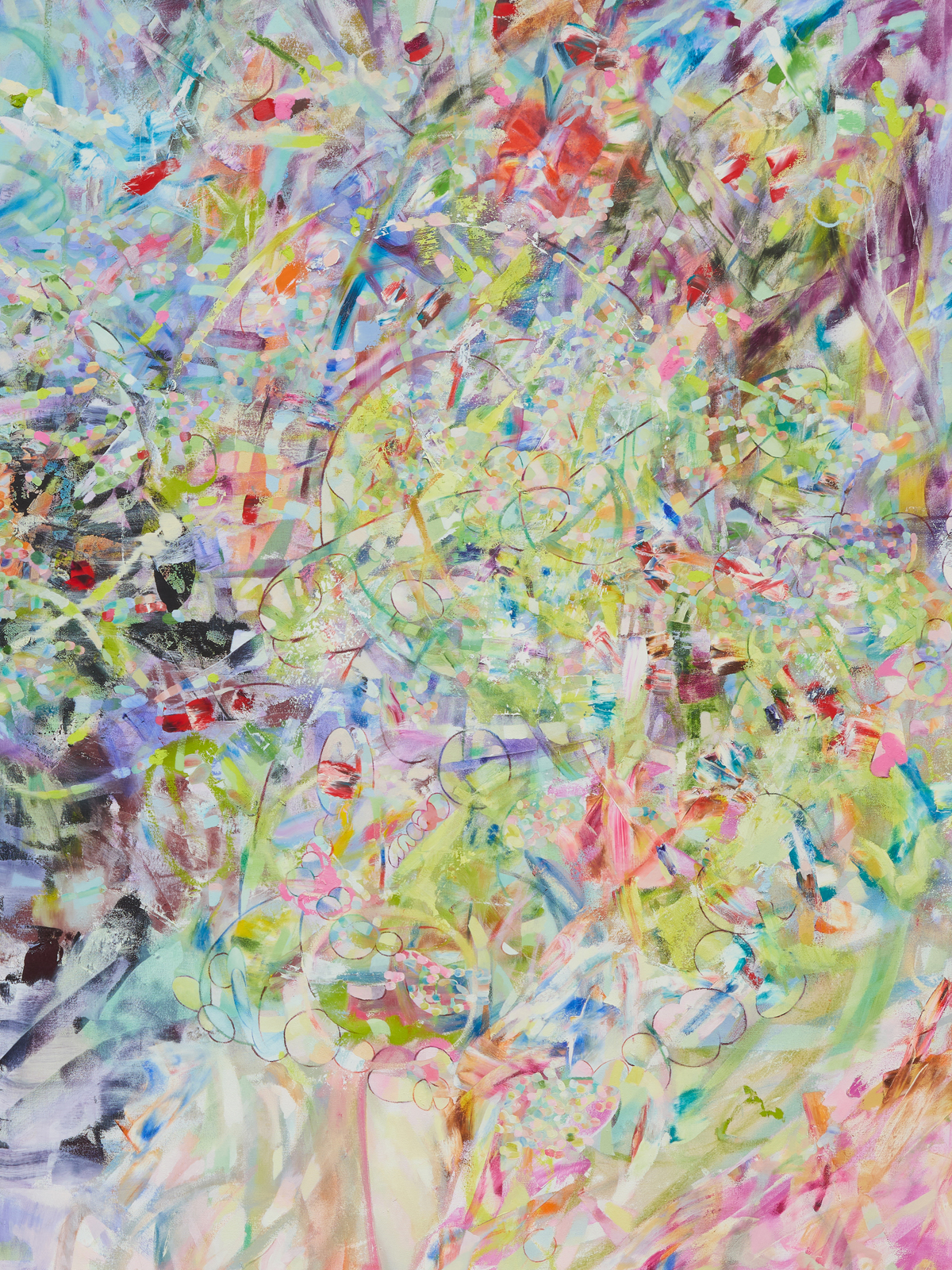

Tsai Yun-Ju, 人間 Live (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 47 1/4 × 94 1/2 in / 120 × 240 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

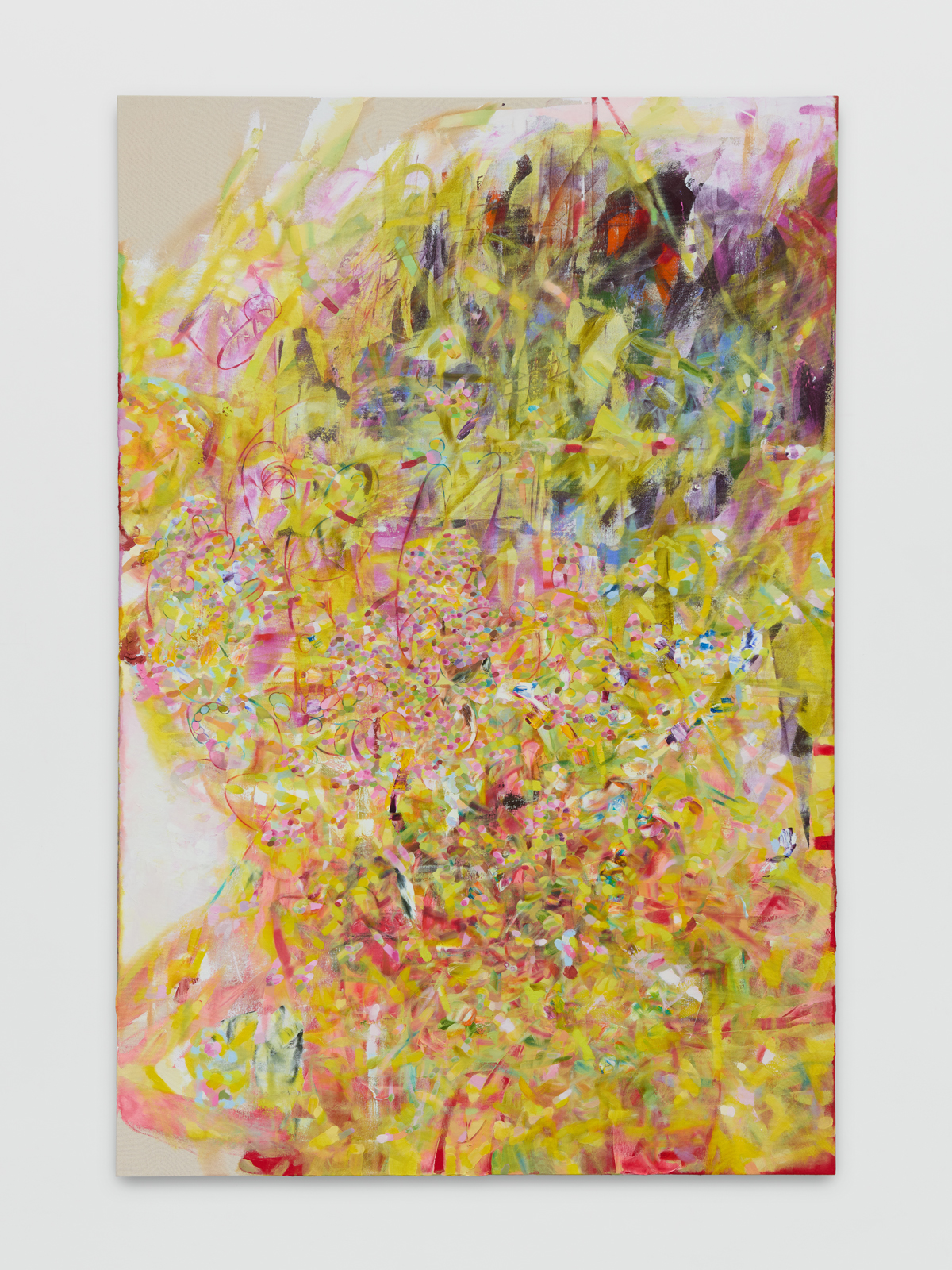

Tsai Yun-Ju, Nautical Promises, 2024. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 47 1/4 in / 200 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, Nautical Promises (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 47 1/4 in / 200 × 120 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 1, 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 1 (detail), 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 2, 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 2 (detail), 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 3, 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 離恨天外 Beyond The Heaven of Parting Sorrow 3 (detail), 2025. Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 × 60 in / 200 × 152.4 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, 天涯共此時 Scythe I, 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/2 in / 180 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 天涯共此時 Scythe I (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/2 in / 180 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 天涯共此時 Scythe II, 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/2 in / 180 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, 天涯共此時 Scythe II (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/2 in / 180 × 120 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, Catalyst, 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 55 in / 180 × 140 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, Catalyst (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 55 in / 180 × 140 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, Comma, 2025. Oil on canvas, 47 1/4 × 47 1/4 in / 120 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, Comma (detail), 2025. Oil on canvas, 47 1/4 × 47 1/4 in / 120 × 120 cm

Installation image from The Sun Never Sets. Tara Downs, New York, 2025.

Tsai Yun-Ju, The Sun Never Sets, 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/4 in / 180 × 120 cm

Tsai Yun-Ju, The Sun Never Sets (detail), 2024. Oil on canvas, 70 3/4 × 47 1/4 in / 180 × 120 cm