Since the 1960s, Roger Winter has charted an idiosyncratic course across the field of painting, generating novel forms of realism. Associated early in his career with Dallas’ vanguardist Oak Lawn painting scene, and, later, with the Penobscot Bay artistic community that also included Alex Katz, Lois Dodd, and Anne Arnold, among others, Winter has long been an established contributor to the history of painting in the second half of the twentieth century. Simultaneously, he has remained an illuminating figure late into his career, producing some of his most perceptive paintings over the past decade, works often oscillating between pictorial representation and geometric abstraction.

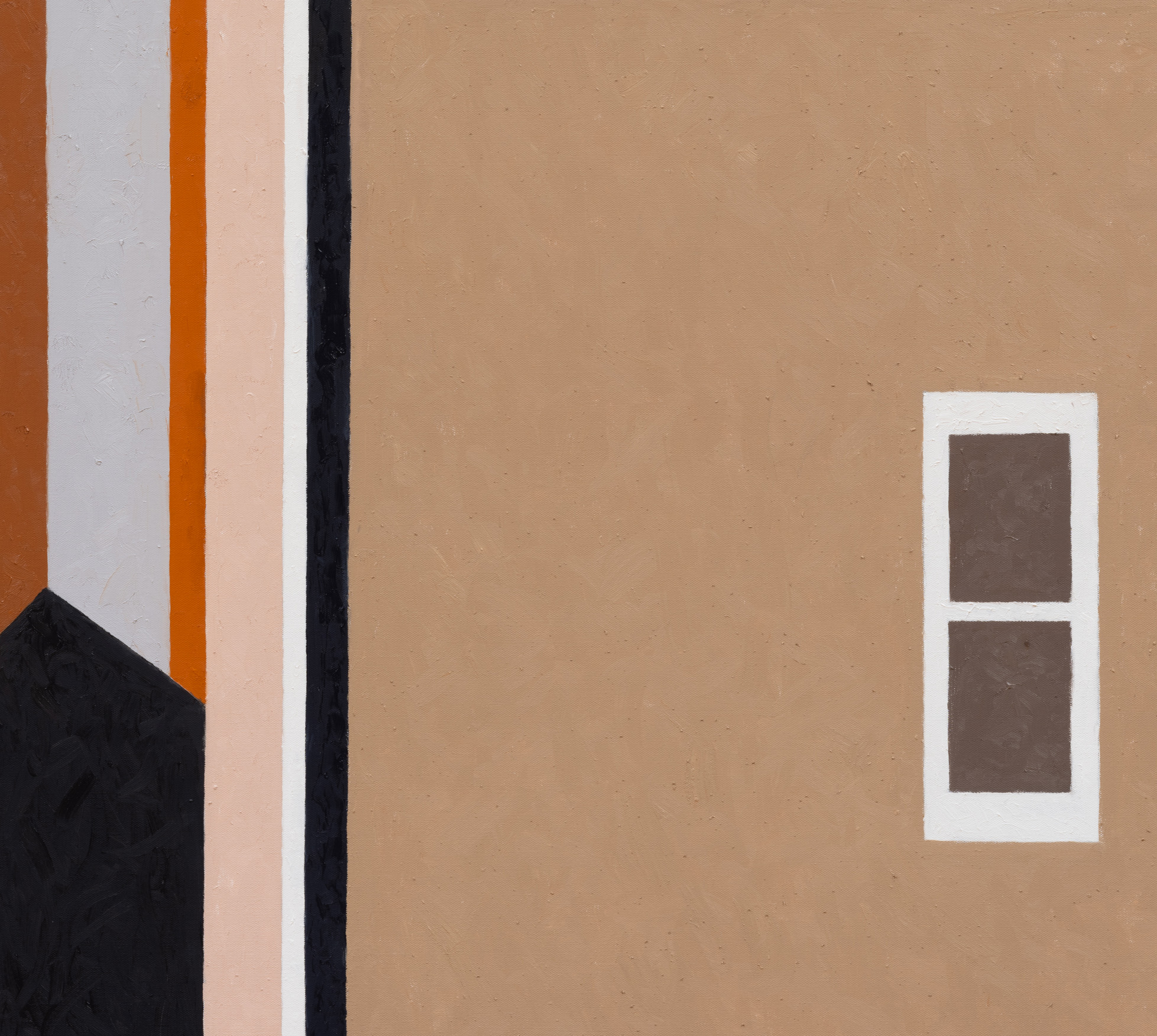

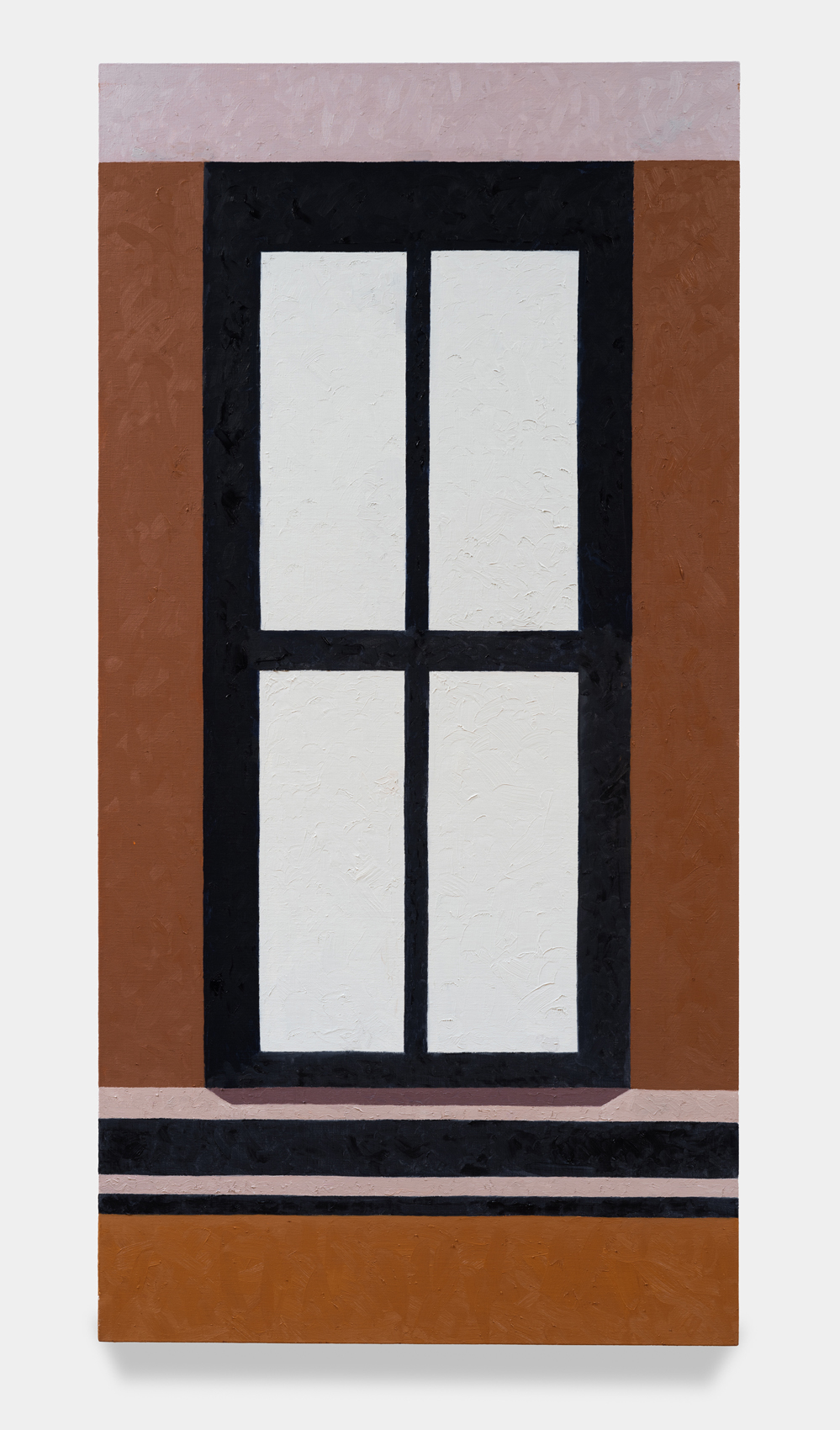

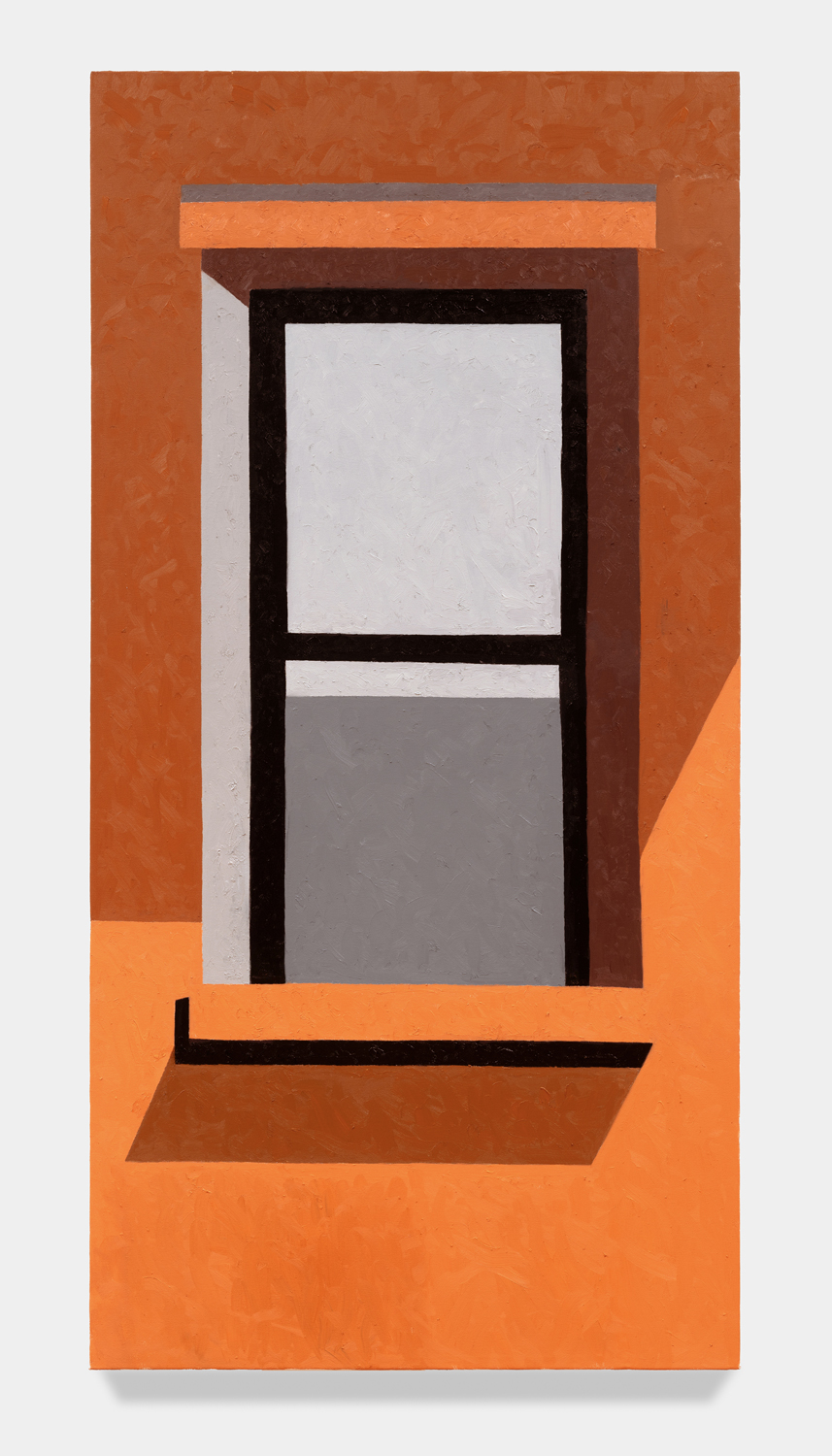

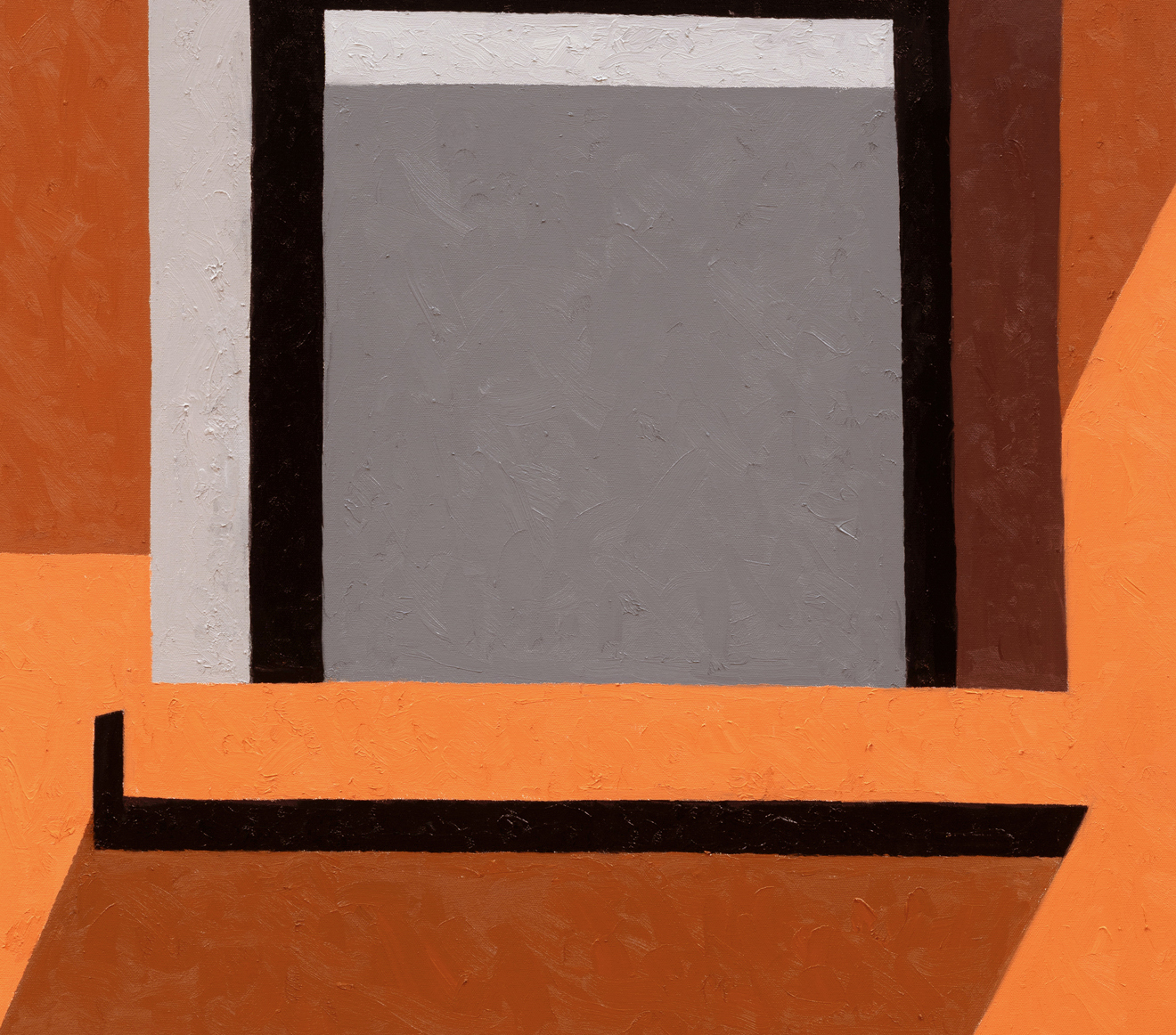

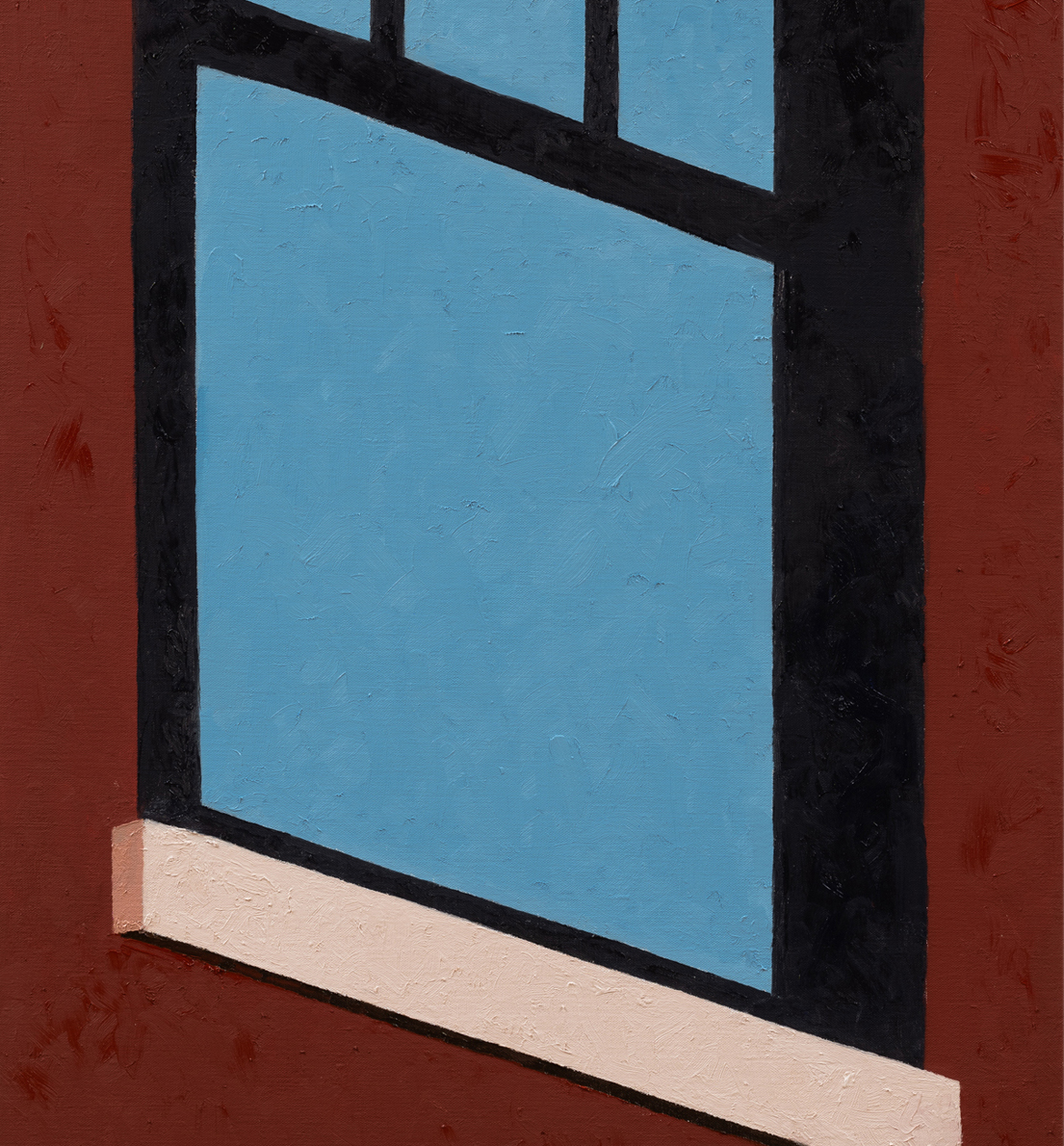

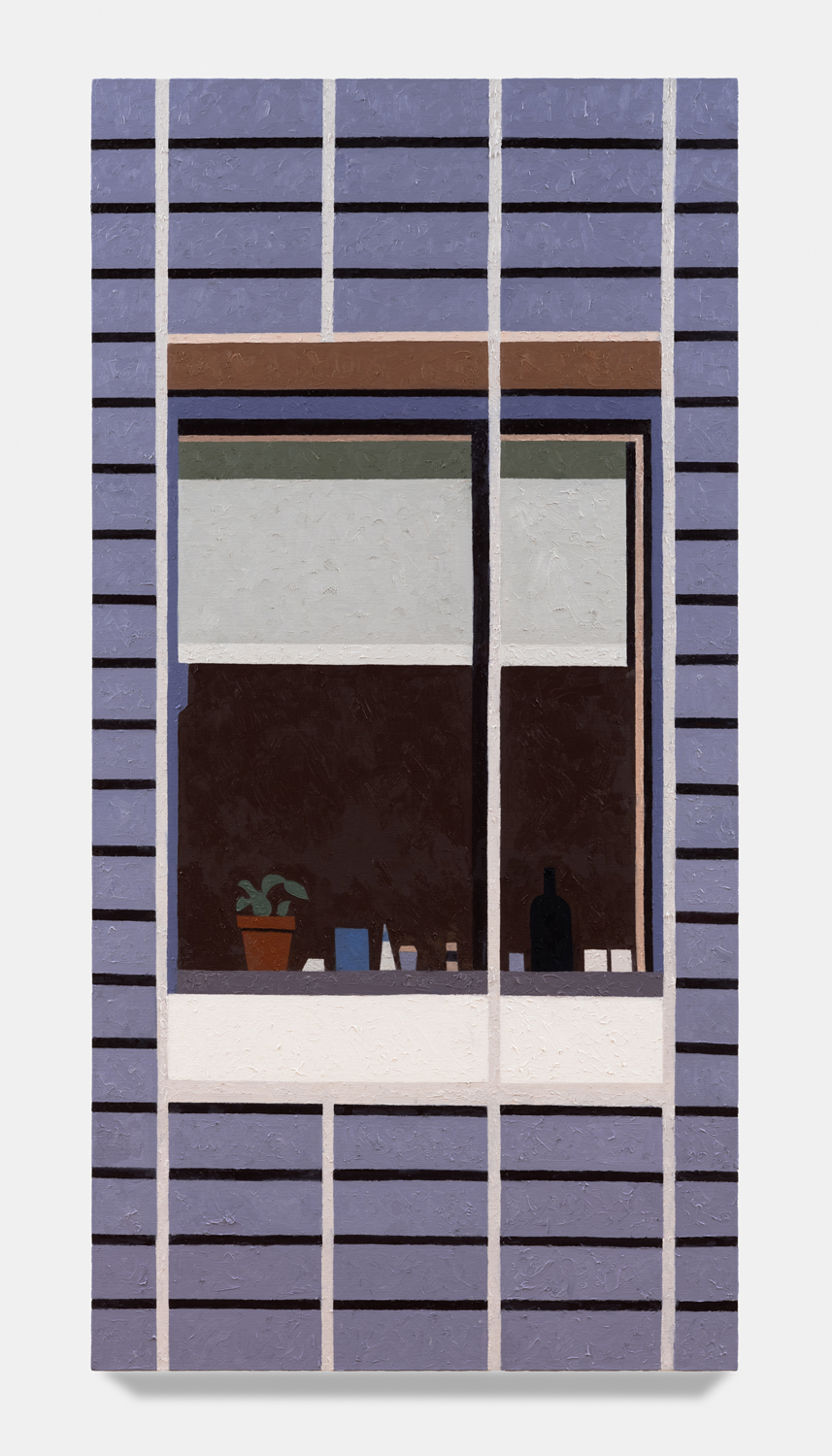

Manhattan Valley, titled after the neighborhood Winter now calls home, centers around a body of work the artist began producing in 2017. Inspired in part by Romare Bearden’s late career propensity for reduction, Winter has cast aside the mimetic virtuosity that often characterized his earlier work in favor of documenting the “cubistic” world we inhabit today, detailing the interactions between architectural space often taken for granted. Windows and walls, oblique angles, odd intersections, instances of incongruity gleaned from the urban landscape. One of the earliest works on view, P.S.93, 2018, elucidates this play of forms, paring an image of a Brooklyn school’s parking lot down to its essential representational components, to broad and dappled planes of color, remarkably brought together in a deceptively simple composition. As Winter’s biographer, the art historian Susie Kalil, has written, such works, seen as abstract patchworks, “are at once in motion and carefully puzzled together, seemingly both topographical and tapestry-like, with the exquisite touch of every painstaking brushstroke.”

This richly textured surface, a product of the stippled brushwork that animates each work, has long been deployed by Winter as a means to undermine the mechanistic impulses performed by painting since Pop art, to insist upon a “painterly realism” even when working in the registers of Photorealism or distancing modes of abstraction. Against the deadpan tonal connotations often engendered by flatness in painting, as in the work of Ed Ruscha, the works on view attest to Winter’s enduring commitment to humanism, the indexical mark of the artist, to storytelling and personal anecdote. Yet in contrast to Winter’s earlier paintings, which have encompassed both portraiture and surreal evocations of subjective significance, the personal here often insinuates itself furtively. In memory of Jean, 2020 for example, dedicated to Winter’s late friend, the poet Jean Valentine, complicating what initially appears to be a partial depiction of an I Heart New York billboard, obstructed, perhaps, by the presence of a high-rise building, rendered in a soft shade of aquamarine. The pictographic heart – a sort of substitute for both New York and Valentine – disrupts the rigid geometry of the composition, bringing it back to the world.

It is often remarked that artists in late career, with prolonged periods of experimentation and exploration behind them, are able to distill their practice to its fundamental concerns, elucidate facets of their oeuvre that have always been there, if only latently, all along. In Manhattan Valley, itself a rather disjunctive phrase, Winter’s affinity toward the landscape of the city crystallizes, comes into view: ever evolving and briskly adapting, it is somewhere new, something else, all the time.