Elizabeth Hohimer’s work always begins in conversation with the land. She approaches her practice with the bold conviction of someone comfortable embracing observable and local phenomena, while working in media steeped in tradition. In her recent suite of weavings and sculptures, she presents a new way of channeling her connection to the desert Southwest, where she is both from and has lived for most of her life. This entails a thoughtful approach to both structure and form, incorporating sensory information through varied materials and processes, such that intention and chance play an equal role. By creating new material narratives, Hohimer explores engagements with the lineage of modernism, counterpointing its formal strategies with a regard for the transcendent—qualities often associated with land art and minimalism—but which converge into a more personal paradigm of place.

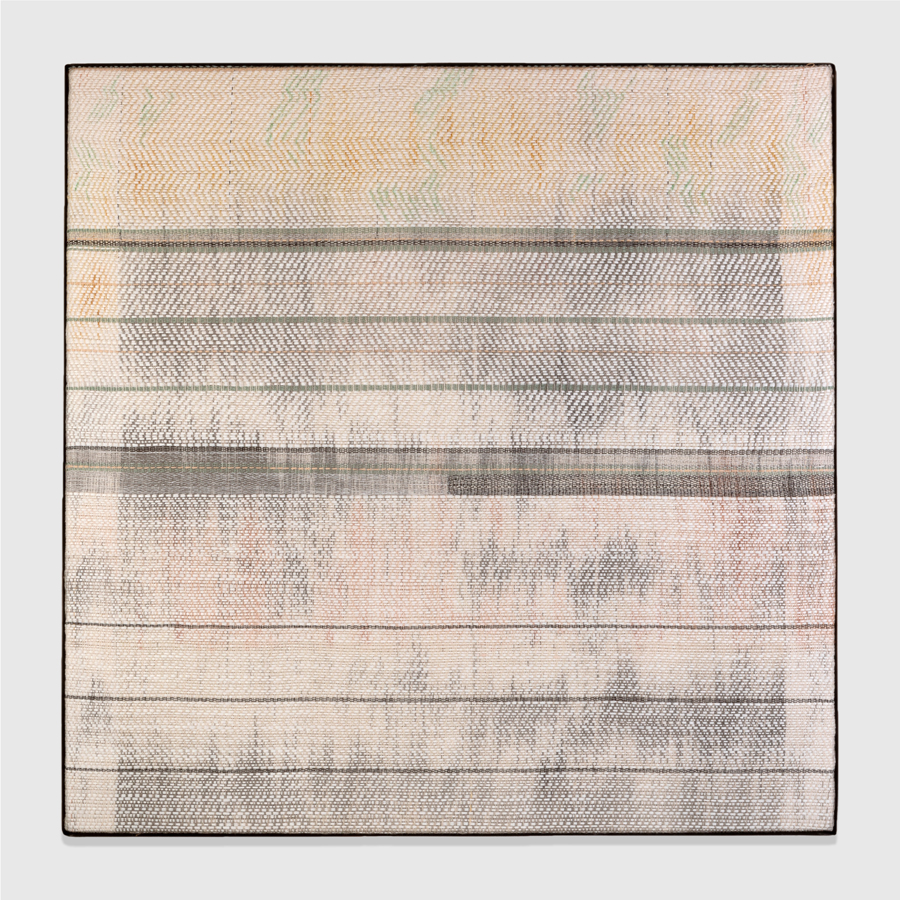

The language built into the process of weaving, the warp and weft as the basis of a fixed formal system, also calls attention to the materiality of the medium, a concept pioneered at the Bauhaus and notably in Anni Albers’ writing. In Albers’ celebrated 1957 essay, “The Pliable Plane,” she writes about the ways textiles imbue our surrounding environment with both spatial and pictorial information and have the potential to partition and thus shape interior spaces in novel ways. In Hohimer’s work, this concept could be applied to a kind of autotelic mapping, where the horizon line serves as a guide for sequences and formal decisions.

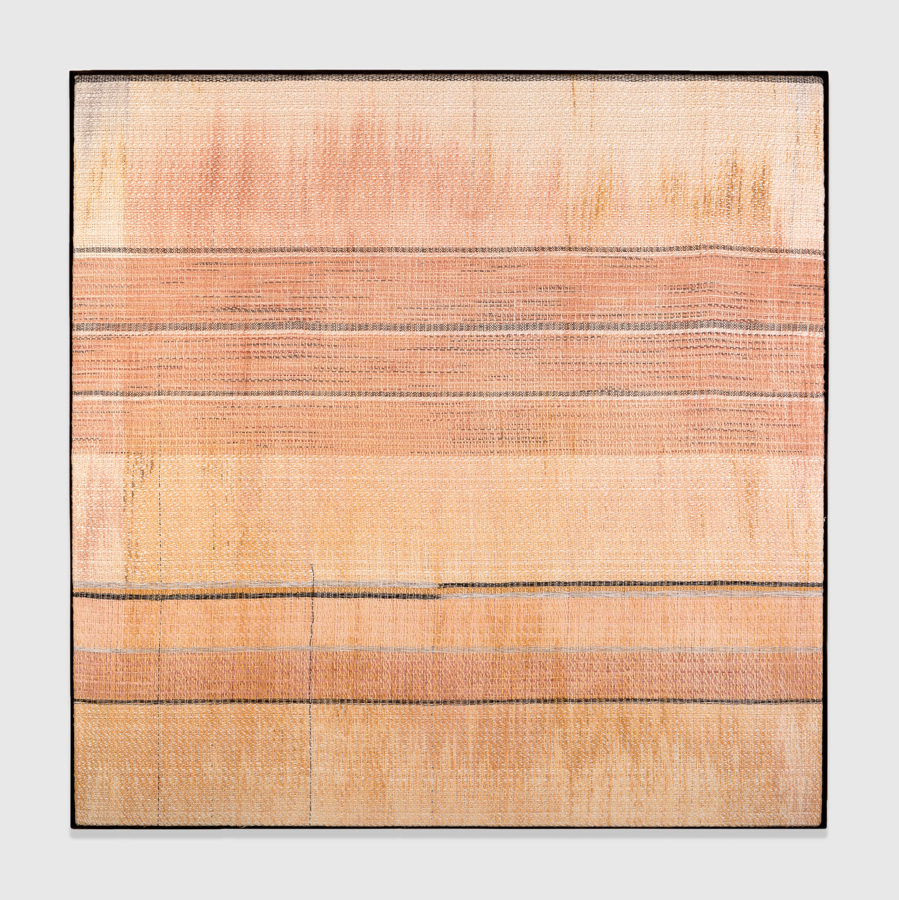

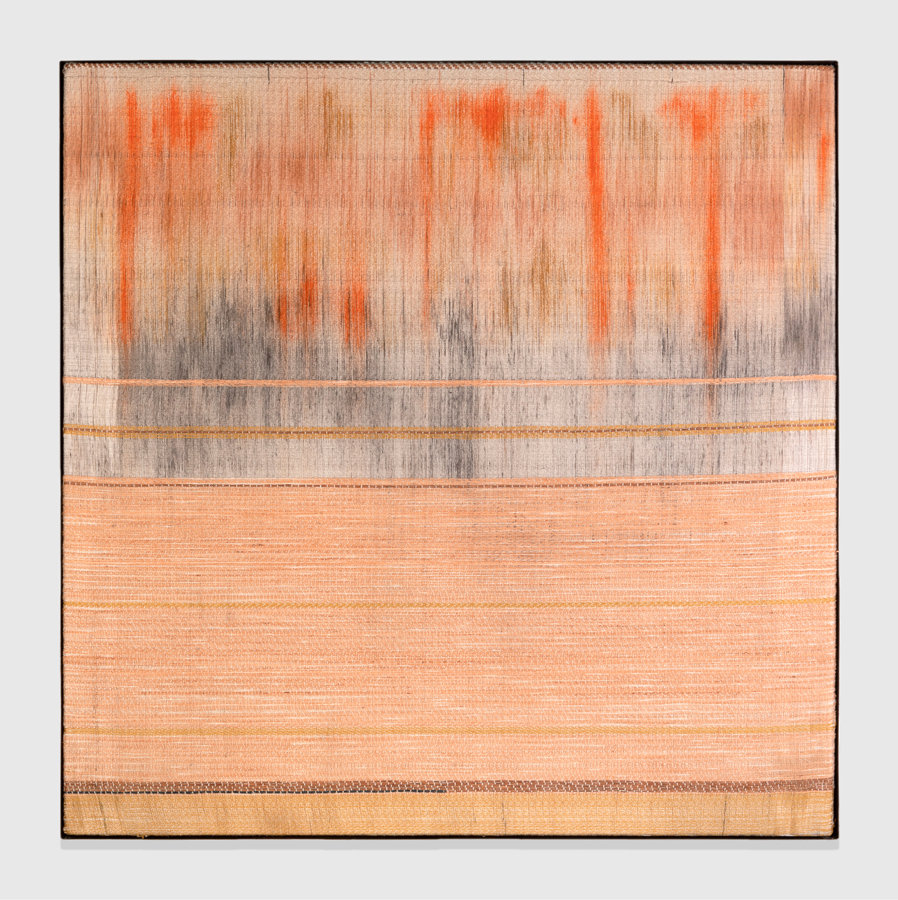

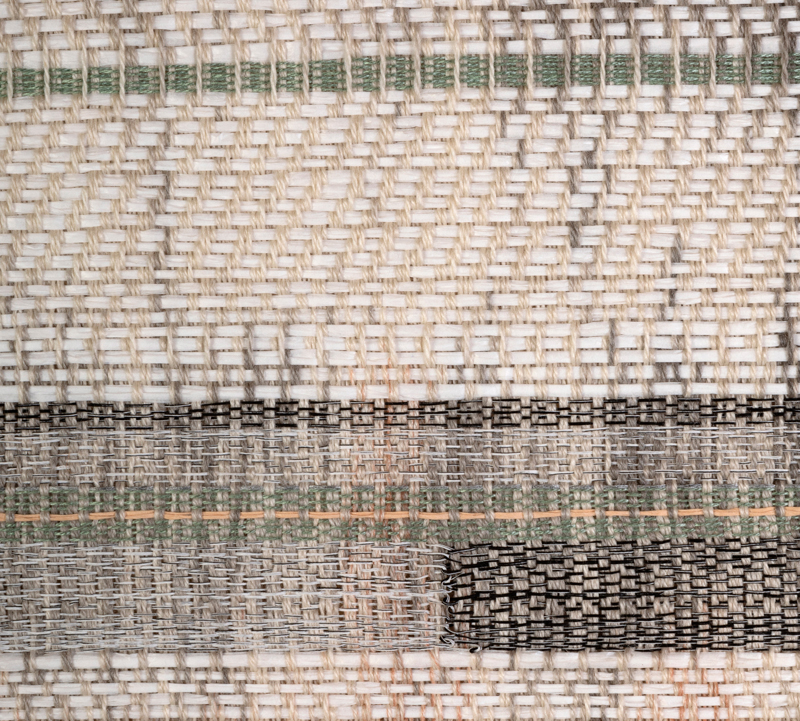

The method by which these works are produced involves the artist entering a nearly hallucinatory state, relinquishing conscious control and allowing memories and emotions to permeate the work. Hohimer winds her warp with thread spun from cotton grown in West Texas and dyed with natural materials, including clay collected from surrounding areas. As she dresses the loom and begins to weave, her hands move in unbroken rhythm. This extended, embodied focus manifests in Color field-like expanses of pigment where closeness and distance blend and the weave’s pattern is imprinted by the land in unpredictable ways. This produces the vertical striations that are most pronounced in works such as Portal to Atonement, and Say Yes To The River, where concentrations of pigment at the top of the compositions seem to portend the swell just before a storm. In other instances, she incorporates pine paper, and sisal or agave fiber, with a specific restraint, embedding the quality of the materials in the overall configuration, while leaving organic signifiers for the viewer to consider.

The desert rewards the economization of energy and movement, and in this stillness, one becomes aware of its subtleties. The vegetation, the weather, and the triumphs of time shaped in rock form a sense of temporality and order. Many elegant surprises complicate the pictorial trope of emptiness and Hohimer is uniquely attuned to this richness. This orientation is given significative function in the vertical columns of agave that compose Totem 3, which the artist describes as a three-dimensional timeline. Approaching the readymade in its rough utilitarian appearance, the bristly strands that hang from this sculpture both repel and attract, an experience that is intensified as one draws closer.

In fact, a repeated motif in Hohimer’s practice is the combination of organic and industrial elements, a common feature of the rural west, a landscape upon which industrial machinery, both new and abandoned, intercuts the vista. Whereas the so-called land artists romanticized the “emptiness” of the west and used the landscape as a framing device for their projected ideas, Hohimer incorporates elements of machinery, raw steel frames and armatures, as framing devices that emphasize an ambiguity of representation and reconcile with the fraught history of redaction inherent to depictions of the West. Hers is a re-structuring of both physical and pictorial space that also meets our perennial desire to find a grounding aesthetics of presence, substance, and authenticity.