Tara Downs is pleased to present Splash, an exhibition of new paintings by the artist Héloïse Chassepot. A skilled artist invested in notions of deskilling, Chassepot here accompanies her durable and incisive notions surrounding the current condition of painting with a number of site-specific interventions, placing her works within a conceptual framework concerned with the subjugation of alterity, with an unspoken opposition to joyful, rapturous, deeply personal forms of making, and the fraught negotiations between so-called high culture and mainstream cultural adaptations of contemporary art.

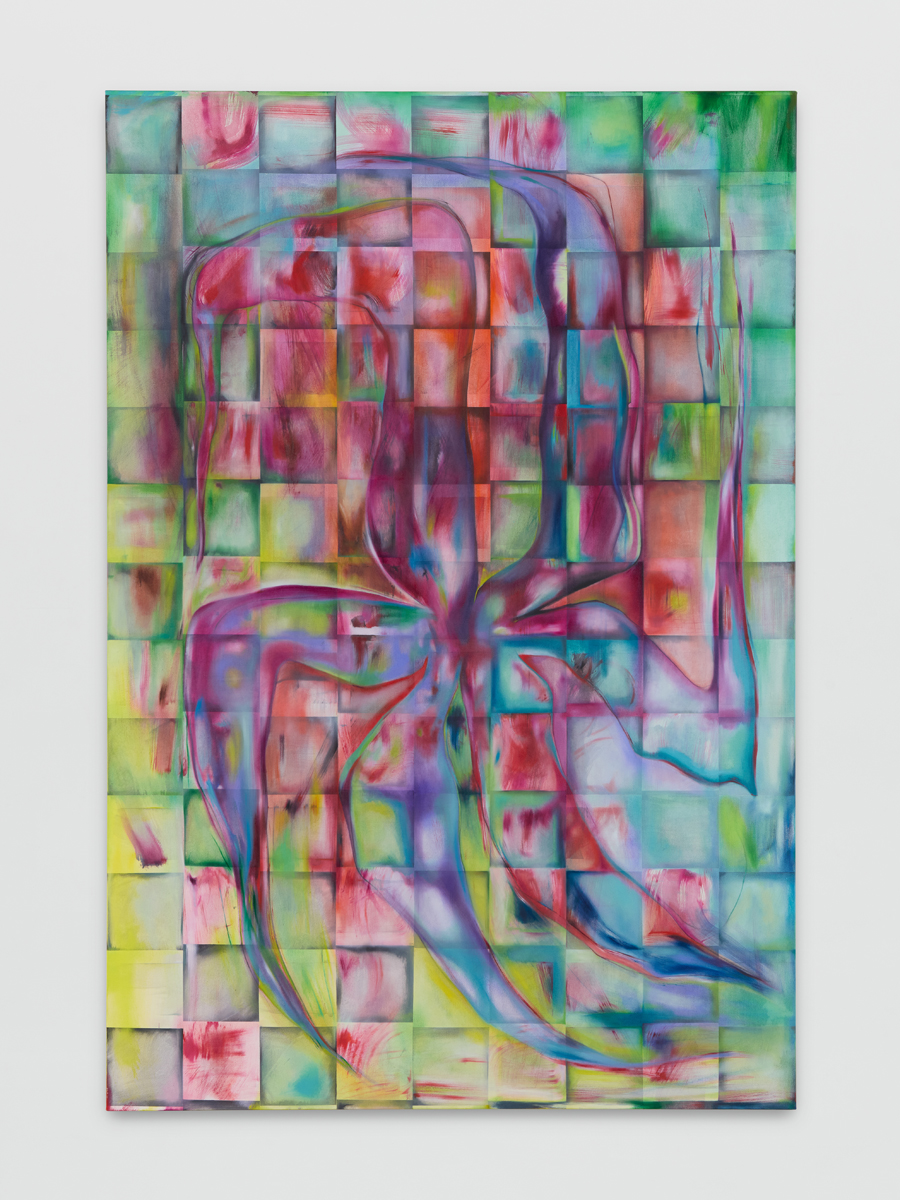

As such, Splash both deepens and broadens Chassepot’s longstanding exploration of the commonalities among lineages of modernist practice, New Age and other outsider aesthetic modes, and painting itself, perceived, in this context, as a commodified form of image exchange. Nearly always grounding her stitched canvases in one deceptively simple depiction – a hallucinogenic flower radiating from the composition’s center – the artist self-consciously capitulates to an overburdened system, one that upholds individuality above all else, while also undermining the logical structure that undergirds its widespread prevalence. Akin to a swirling vortex or a Buddha’s hand, Chassepot’s artistic signature threatens to overtake the canvas and envelope everything surrounding it, playfully mocking painting’s hegemony. Against this particular understanding, however, the distinctive palette of her works – similarly radiant, yes, but also brilliant, almost Day-Glo – may conjure more minor forms of cultural production, such as psychedelic art and, in particular, 90s rave culture (an influence tacitly acknowledged by the work Technoflower, 2024), even as it remains conversant with a much longer history of non-representational color theory, especially redolent of the Fauves’ emphasis on harmony and balance. Likewise, the artist’s development of this organic figure derives from a serious consideration of painting’s operative principles, how seemingly universal symbols may be emptied of meaning through replication, or how Western modernism’s great motifs – whether Monet’s lily pads or Pollock’s splatter – have evolved over time.

That splatter returns in Splash as a cheeky form of self-awareness and cunning acknowledgement of action painting’s legacy – from primal expression of subjectivity to splash wall – as a decorative moment of installation art. Yet although our minds may begin to wander toward one specific trajectory of Pollock’s own signature – the splash of the exhibition’s title, of course – from defining gesture of high Modernism to DIY interior design hack, it’s clear that Chassepot’s treatment of these analogues between contemporary art and various aesthetic forms, whether subcultural or HGTV, is dualistic rather than wholly diachronic. She is less bothered by the degradation of these modes of artistic activity than she is intrigued by the notion that these forms may exist alongside one another. And we may say, further, that the inherent duality of her practice was already anticipated by Roland Barthes’ two-tiered definition of the amateur, as “someone who engages in painting, music, sport, science, without the spirit of mastery or competition,” but also “one who loves and loves again.” In other terms, the Sunday painter, unskilled yet fully dedicated to their own idiosyncratic project, is singularly able to unleash the unbridled passion of their craft, unconcerned by how it might perform or resonate in a broader context. Acting in the role of the Barthes’ amateur, Chassepot opts out of a system that demands easy legibility, throwing a wrench in the machinations of a market that would prefer to view contemporary art as a game of card collecting. Yet while Chassepot’s paintings may question their position within a global network of image exchange, they also enable the artist to return, again and again, to her primary preoccupation – the ecstatic process of pure painting.