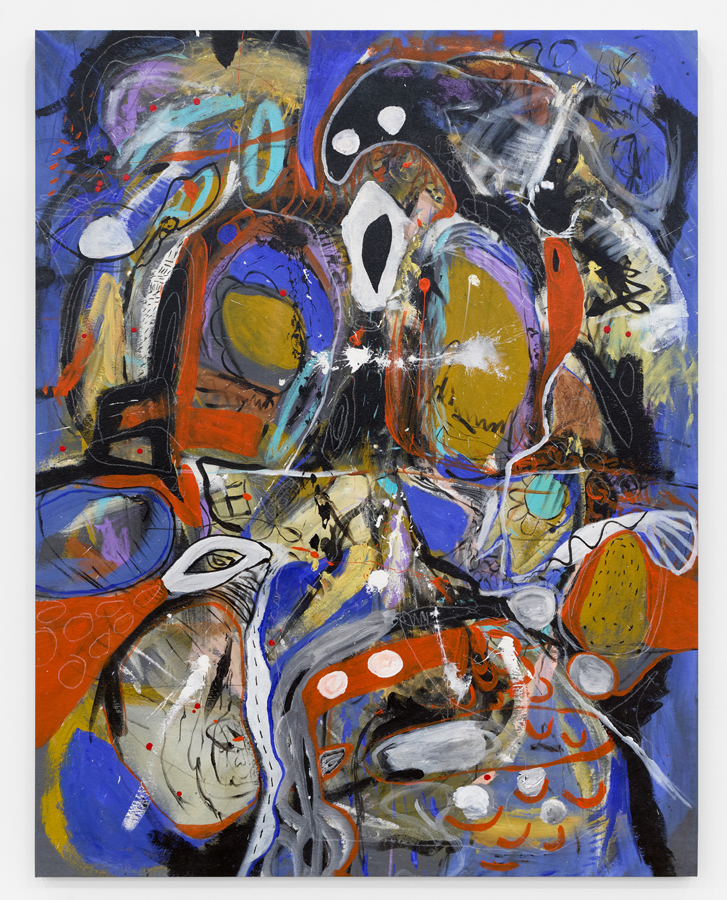

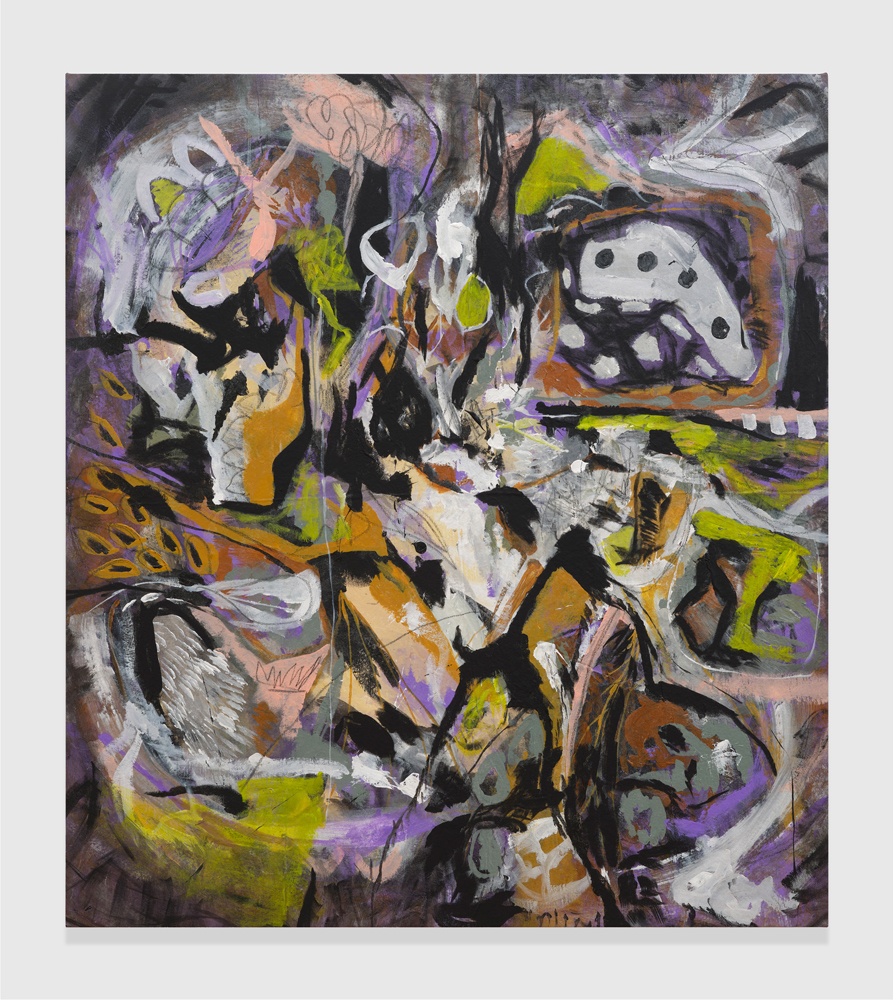

The Year of the Vampire, Nizhonniya Austin’s first solo exhibition with Tara Downs, comprises a suite of large-scale paintings produced over the last year. Drawn as much to representations of the Southwestern landscape as to histories of painterly expressionism, Austin works from a method of free association, producing enigmatic compositions from a dense network of indexical marks, which manifest a nearly map-like rendering of the artist’s interiority, her keen sense of deliberation and intuition. Born in Juneau, Alaska and based in Santa Fe, Austin (Diné and Tlingit) elucidates the potentialities and complexities of working as a Native artist within the global context of the contemporary art world, while Austin’s painting practice operates within a broader framework that also includes performance and professional acting.

Each work on view – maximalist paintings carried out in saturated and often inorganic shades of color, stark blacks, and vibrant blues – chronicles deeply subjective material, inseparable from, but also additive to, the artist’s work in performance. The conspicuous standardization of the canvas – each large and square, measuring 52 × 52 inches – begins to suggest a one-to-one encounter between artist and surface, a sort of diaristic frame in which Austin may evoke, for herself and for us, the affective tenor of internal experience. As paratextual devices, the work titles are always evocative (The Summer I Swam Through the Thicket of Hocus Pocus Phenomenon) and often wryly funny (The goth bad boy supreme), informing our interpretation of the works as outward manifestations of interior recollection. At the same time, Austin’s energetic recontextualization of the non-perspectival landscape remains conversant with contemporary Indigenous artists. Like fellow Diné artist Emmi Whitehorse, for instance, Austin constructs dense, disorienting landscapes, charting manifold associations among a deeply personal lexicon of symbols and gestures. Yet rather than elucidating an imagined or impressionistic sense of cartography, Austin’s paintings instead inscribe her own experience in a longer, more complex history of abstraction.

To note, all of this unfolds within a reexamination of Native art’s historical influence on the history of abstraction, and particularly the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. A revised Triumph of American Painting, after Irving Sandler’s seminal 1970 chronicle of AbEx, must today account for more inherently American forms of making. In her insistence upon the centrality of process to her work – her emphasis upon the essential relationship between artist and surface – Austin recalls, for instance, the influence of Navajo sandpainting on Jackson Pollock’s development of the drip. Yet while such connections never manifest didactically or illustratively in The Year of the Vampire, the paintings on view do begin to suggest an alternative history in which these correspondences were considered seriously and posited as a generative site of inquiry, rather than left to languish in the margins, as footnotes and parenthetical asides. In displacing contemporary art’s obsession with iconicity, by constructing a dialogue between the supposed durability of the painted image and more ephemeral modes of artistic production, Austin evinces how the act of painting itself may become the message.

Rather than ancillary or adjacent to Austin’s studio practice, the artist’s performance work is integral, providing opportunities for Austin to reflect upon and complicate her unique position as an artist. In the recent television show The Curse, a dark satire created by Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie, for instance, Austin portrays Cara Durand, a Native artist living in Española, New Mexico. The arrival of a film crew to shoot an HGTV pilot hosted by a pair of husband-and-wife real estate developers, played by Fielder and Emma Stone, implicates Austin’s Durand more than most. A successful local artist aspiring toward broader recognition, Durand is in a specific bind – involving herself with the production presents a substantial opportunity but also risks giving cover to the show’s cheery gentrification premise, not to mention selling out (or, worse, appearing to sell out) the political dimensions of her artistic practice. As Bruce LaBruce wrote in Artforum, “the character is a complex dialectical portrait of the artist as a young Indigenous woman negotiating all the ethical potholes that contemporary artists are heir to.” Austin’s discomforting portrayal sings in part because of its metatextuality; like her character, Austin, too, is navigating the fraught terrain of appearing as a Native artist on television. And, as the exhibition title might suggest, something of this exploration translates back to The Year of The Vampire.