A return to the “problem of the snail.” In Francesco del Cossa’s painting The Annunciation (1472), the archangel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary in an ornate Renaissance palazzo, a deep and open space that enables Cossa to present an awe-inspiring amount of architectural adornment. The painting is a capriccio, much like Piero della Francesca’s earlier Annunciation (1455), but also an example, contra Piero’s perspectivally accurate depiction, of rendering imaginable an impossible architecture, in this instance, of Mary’s anachronistic abode. It is easy to lose oneself in this maximalist labyrinth, to give oneself over to the presented illusion; only recent attempts to model the space architecturally have confirmed its unattainability. But then, as the late art historian Daniel Arasse confides to us in his incisive study of the painting, Cossa built a tell into his schema, one that slinks along the edge of the canvas, disproportionate to its surroundings, as if, in actuality, resting upon the painting’s frame: a snail. An oddity within annunciation paintings of the Quattrocento, the snail at first seems arbitrary and its presence cannot be deduced through iconographic interpretation alone. “On the edge, at the boundary between its illusory space and the real space,” [1] per Arasse, it is this gastropod – the ostensibly minor, even whimsical, detail – that gives lie to the whole scene.

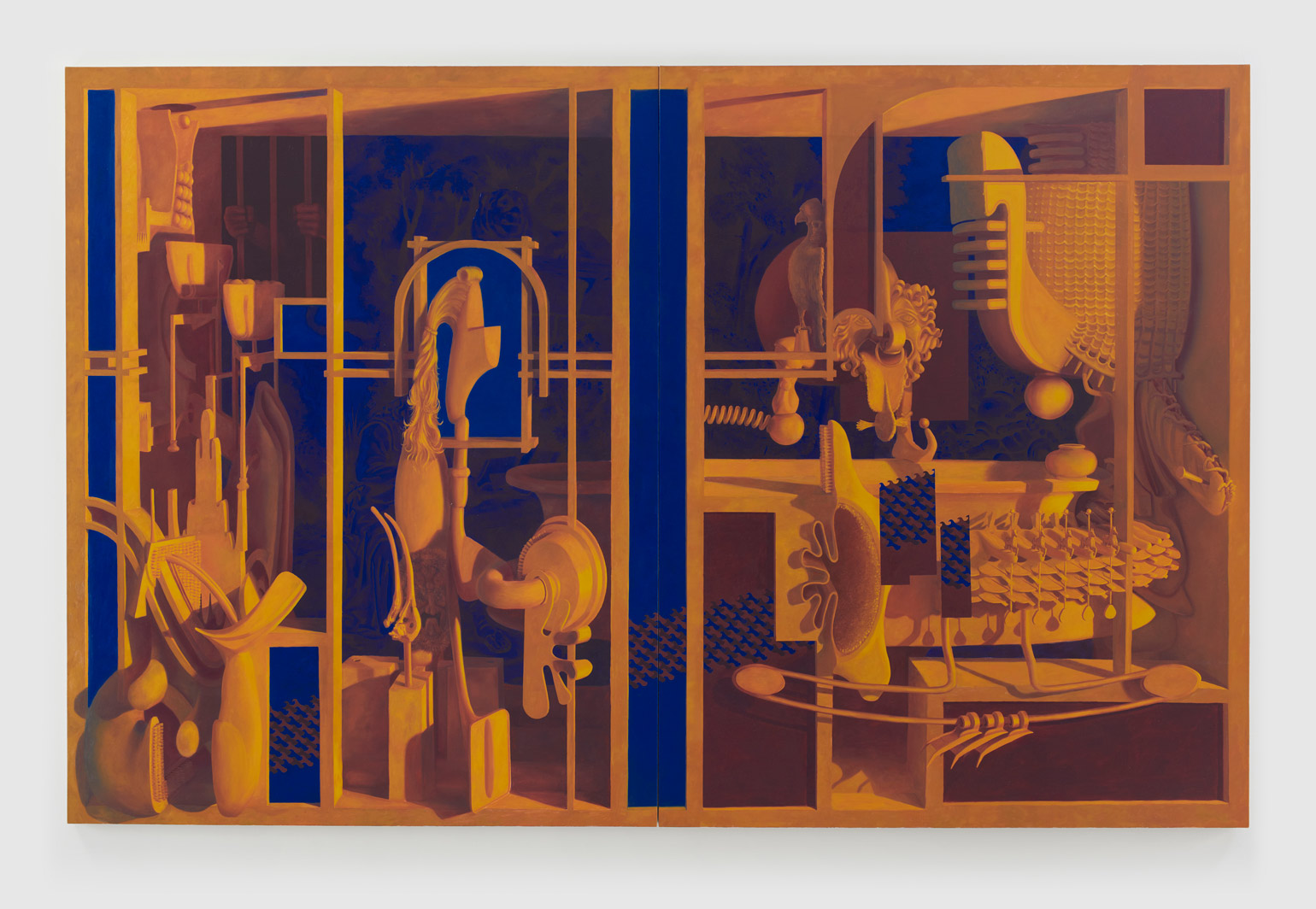

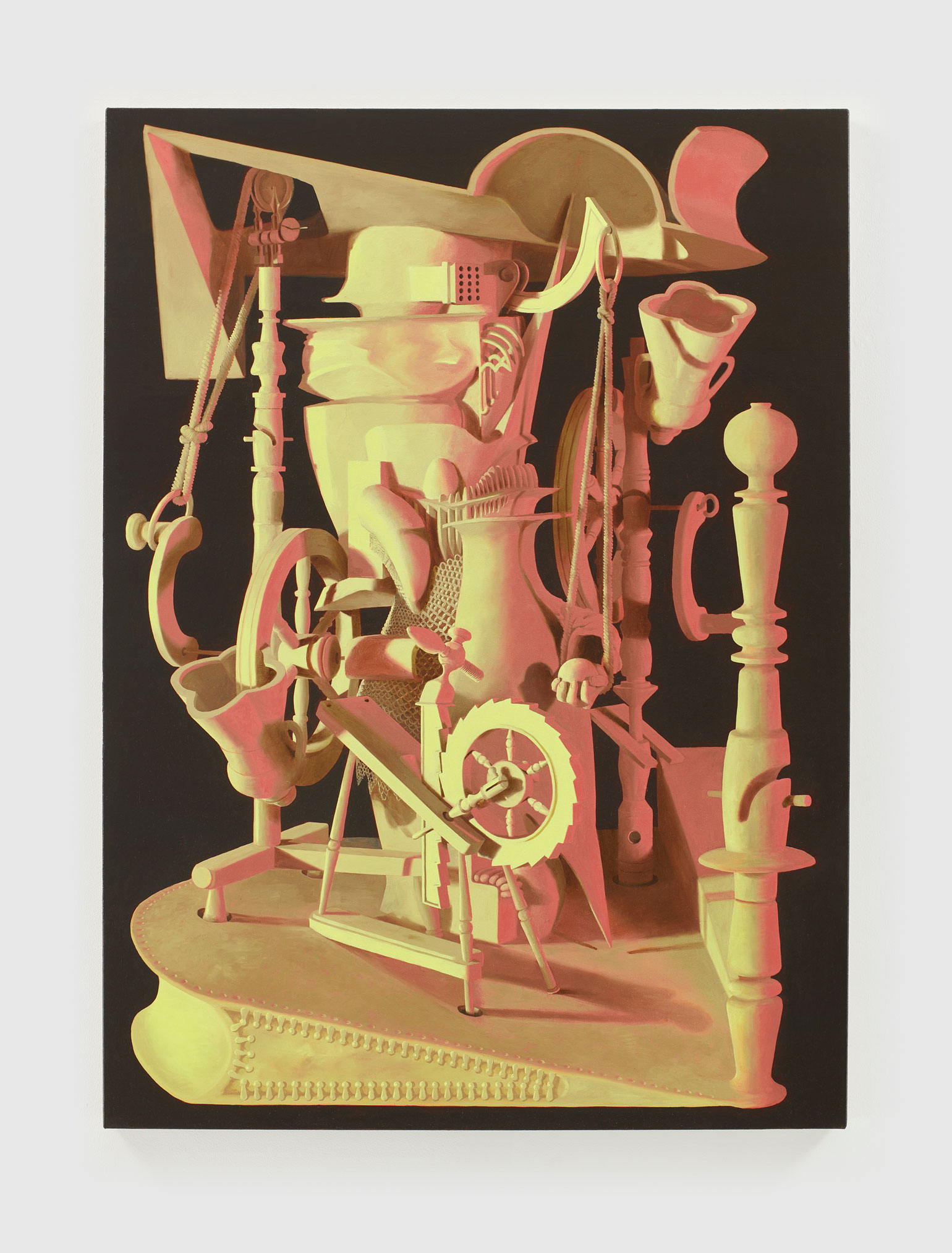

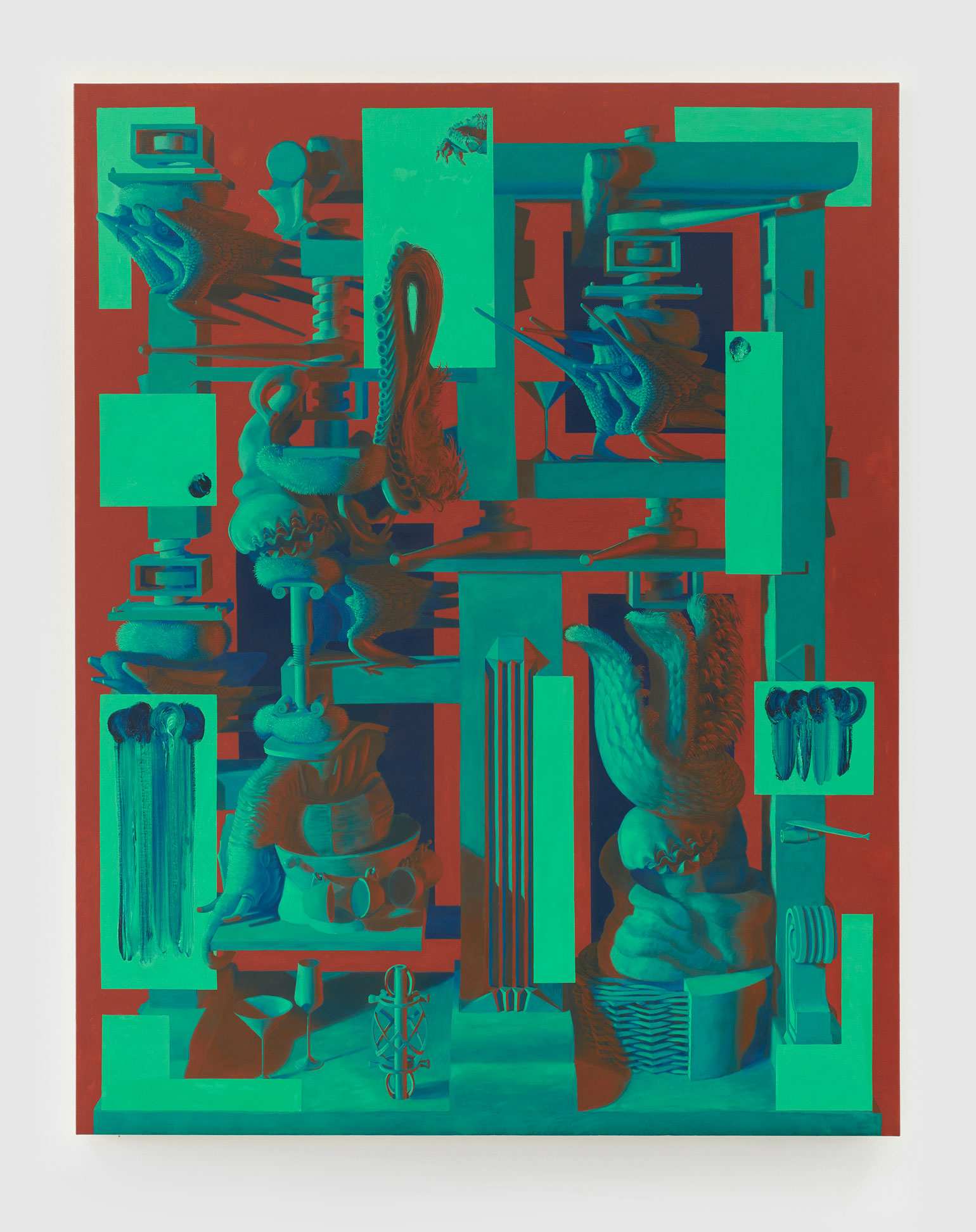

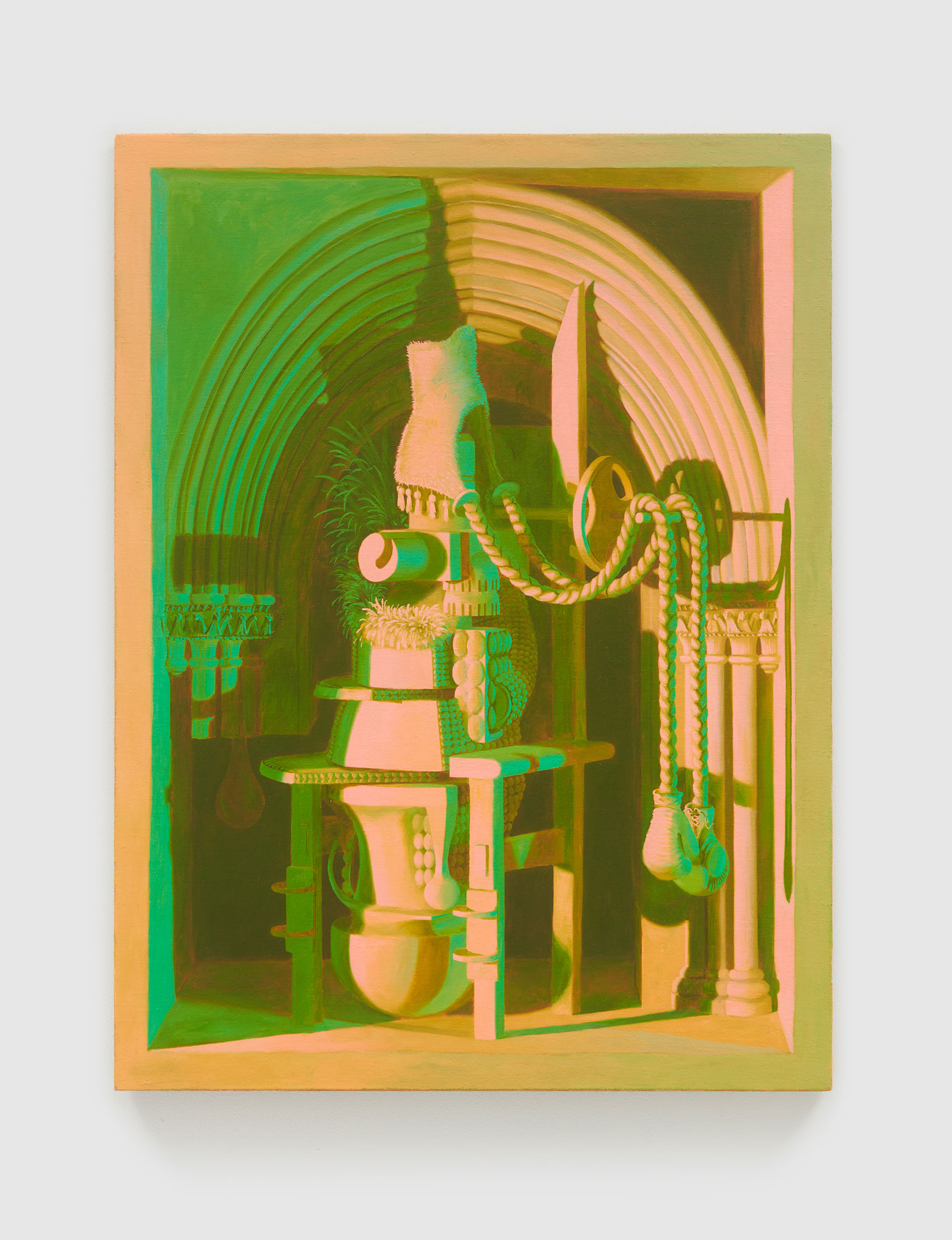

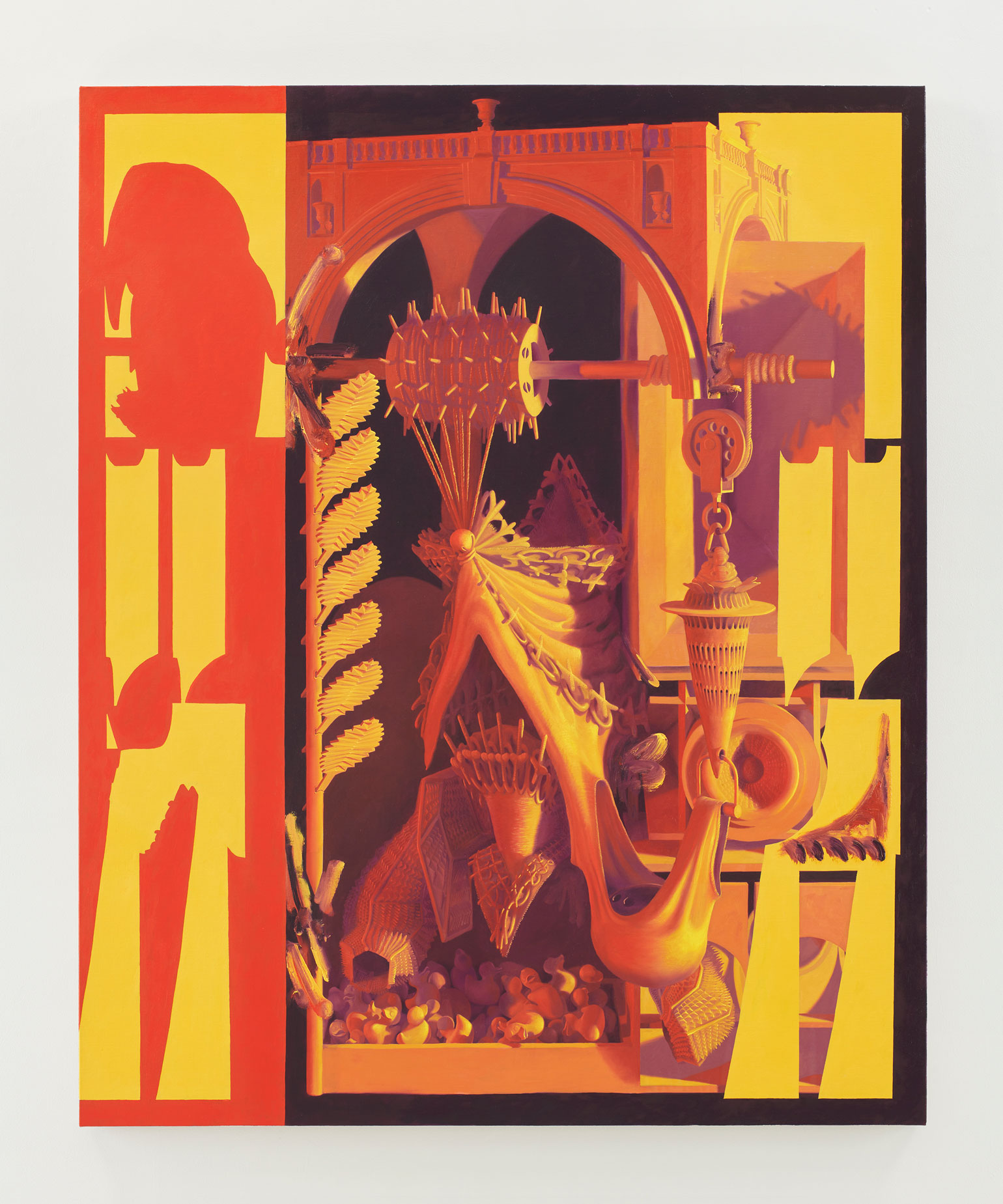

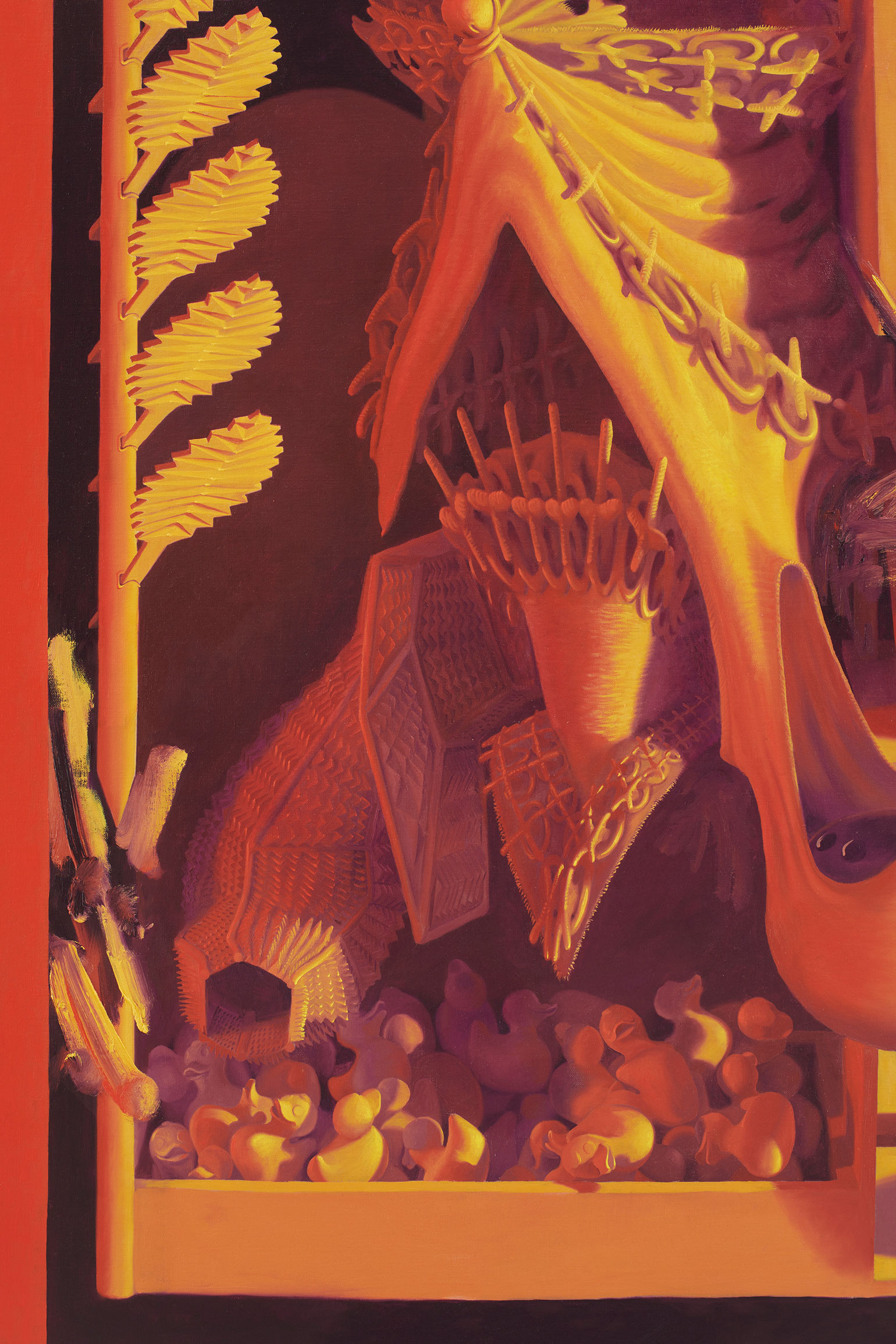

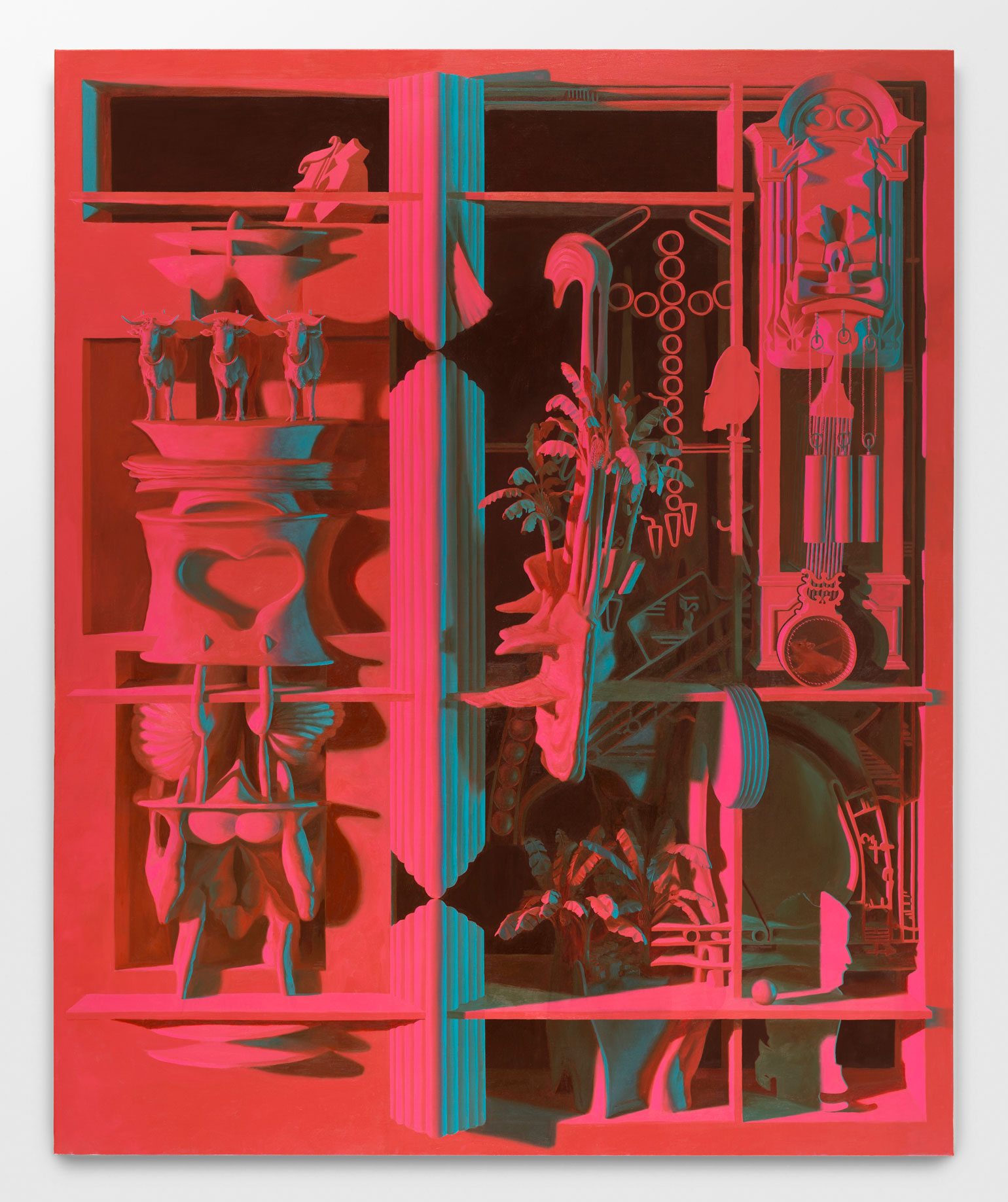

This is precisely the sort of pictorial dilemma – an irresolvable skirmish between perspective and errant detail, between illusion of depth and its deconstruction – one encounters in the densely composed oil paintings of London-based artist Tom Waring, whose new body of works compose Ars Brevis, the artist’s second solo exhibition at Downs & Ross. It is perhaps only within these works, each an elaborate feat of architectural and mechanical configuration, where the closed interior space introduced by Duccio and Giotto may be disrupted by a pile of rubber ducks (Pinquing, 2022), where a hydroelectric dam may simultaneously function as a coat rack (Kloomerhout, 2022), where flat planes of color may provide space for an expressive gesture or, indeed, house a crustacean (Auguerboss, 2021). As this brief inventory may suggest, Waring’s practice not only focuses profoundly on early Renaissance history, but takes a materialist understanding of humanist painting as its raison d'être, pondering how questions of impossibility, both technical and social, drive the establishment of painterly tropes, spanning from the excesses of Mannerism through Futurism’s compounding celebration of auto-destructive speed and draconian social currents. These works read epistemic shifts in visual culture barometrically, as if they were signifiers of political health. As such, many of the works at hand contend, acutely, with the reverberant disasters of British colonialism, signaled not only iconographically, as in the neon-singed banana palms of Duell (2022), but also through their stuttering, still recognizably Anglophonic titles. While grappling with this specific history, these works also seek, more generally, to redress the durative cultural unease surrounding urbanization and industrialization, both processes nearly synonymous with the advancement of modernity. Perhaps it is for these reasons that when more figurative elements emerge in Waring’s paintings, they often suggest either incarceration and subjugation – just look at the hands clasping prison bars amidst the deep-blue chinoiserie of Euedecker (2022), or, just as well, the hooded falcon of the diptych’s second panel, the yoked oxen of Duell (2022), the bird cages of Afashjungdi (2022), and, most indelibly, the impaled toed stiletto of the same work. Waring’s insistence on the latent horrors of Western visual signifiers, particularly those bound to technological development, is underscored throughout these works by the consistent appearance of the gargoyle, a grotesque commonplace of the Gothic period. This grimacing creature functioned simultaneously as an ornament and drainage feature, yet is here put to other uses, as in Euedecker (2022), where the glowering creature crowns a children’s carousel.

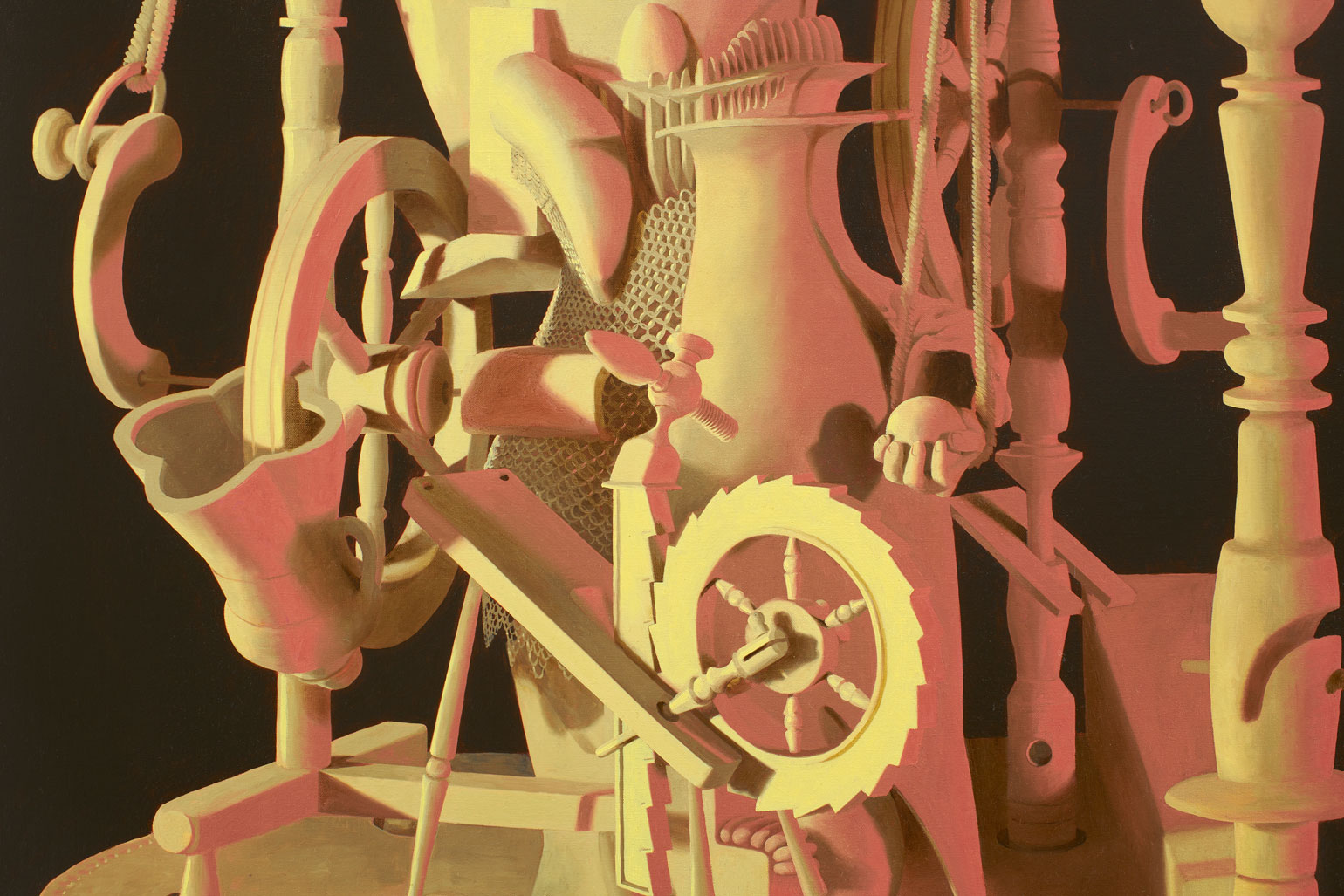

Ars Brevis further elucidates Waring’s enduring engagement with the writings of 13th-century philosopher Ramon Llull, drawing its title from the abridged version of Llull’s iterative masterwork, Ars Magnus. Llull, whose aesthetic arcana and exophilic philosophy coincide with the birth of artistic humanism, and who is increasingly regarded as a forefather of computational theory, fittingly serves as a lodestar for the new works on view. In this context, Ars refers not to art in the current sense, but rather technical skill, a winking nod toward Waring’s deployment of grisaille, the Old Masters technique of underpainting, which accounts for the sense of depth characteristic of the artist’s work. This old technique is compromised by the artist’s approach to color coordinated bidirectional lighting, a setup often associated with synthetic and screenic sources, and particularly images produced via 3D rendering software. Against those allusions, Waring’s works are predominantly born from an automatist approach to composition building, taking into account certain 20th century artistic movements like Surrealism and CoBrA, while unexpectedly, astonishingly departing from them in one important regard: the cogs and gears, synthetic fauna and organic flora, architectural elements both classical and contemporary that appear before us are all convincingly rendered sans studio models or preparatory sketches. Reverting to the exhibition title once more, yet another valency surfaces, this time on the edge of irony: a truncation, and accordingly an inversion, of Hippocrates' first aphorism: “ars longa, vita brevis.”

[1] Arasse, Daniel. “The Snail’s Gaze: The Annunciation, Francesco del Cossa.” In Take a Closer Look, 17–38. Princeton University Press, 2013.