Every waking moment, earth is inundated by an inconceivable supply of solar radiation. We cope with this immense surplus of energy by terraforming agricultural landscapes, routing giant textile mills, and powering an industrial churn of globalized consumer goods; efforts, all of which, may never fulfill the great economic supply chain the sun provides. Despite this overabundance, a growing consensus of public research studies signal inflation as our top concern, trumping crime, climate change and immigration. As a near universal devaluation of fiat currencies bleeds everyday savings, doubts of labor-time and our ledgers of holdings are evermore exacerbated. Questions of wealth, its future deferment, and ancestral stores of value continue to reorient our thinking, behaviors, and even lifespans. How then do we store the sun?

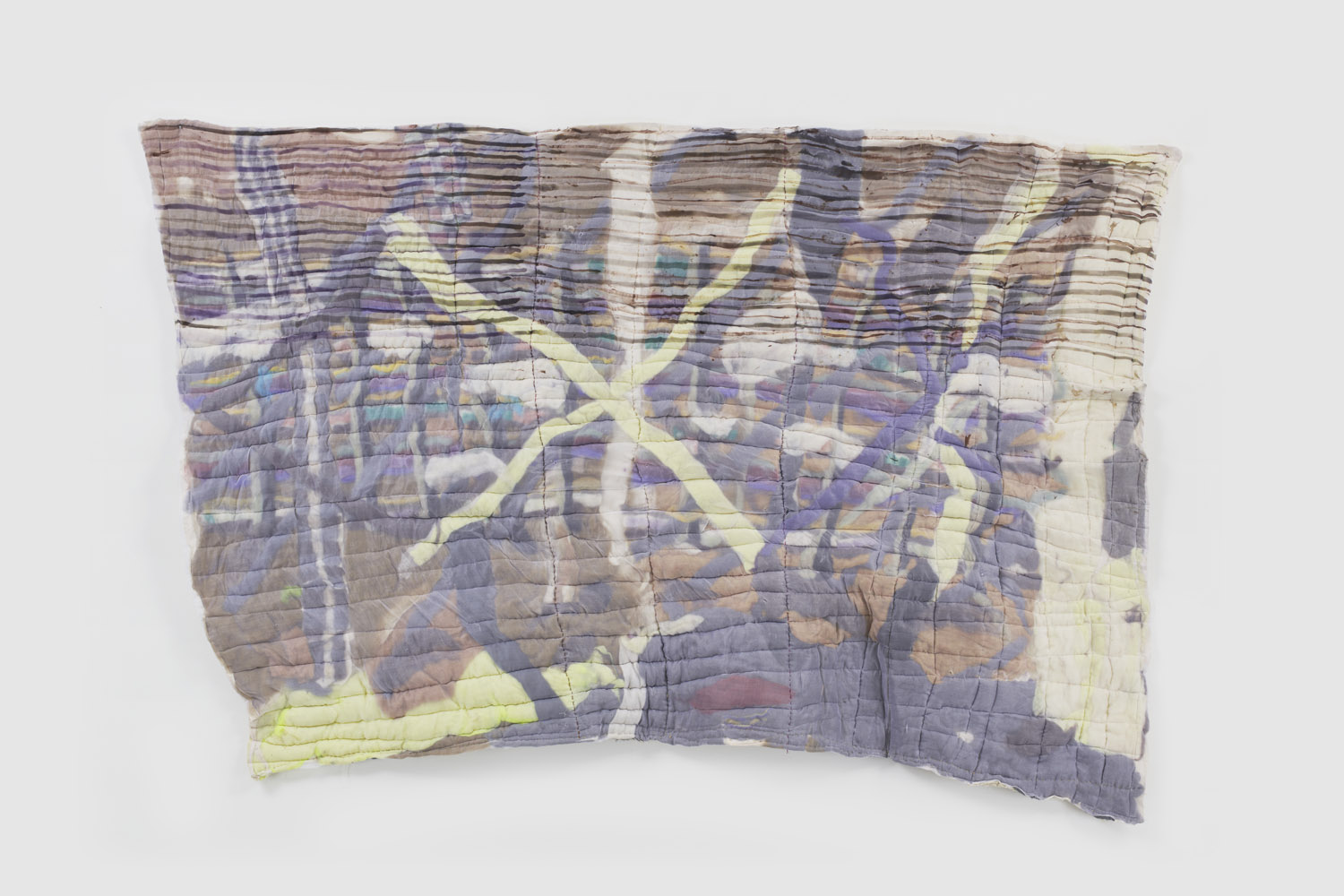

The typically immaterial processes undergirding these anxieties—global flows of capital, transfers of wealth and commodity supply chains—find form in On Grist and Sunstroke, an exhibition of new works of domiciliary orientation by New York-based artist Justin Chance and Paris-based artist Kim Farkas. Here, Farkas presents five suspended biomorphic sculptures, lamps lambent with the diffuse glow of fluorescent lights. Embedded within these liquiform encasings are miniaturized plastic facsimiles of consumer items and edibles that are the objects of broad ritual use among an international Asian diaspora, counting among these a Bruce Lee statuary and fiat currencies. At once artifactual and architectural, the works’ tubular and lambent silhouettes echo the financialized origins of an evolving Singaporean nocturnal cityscape – a hub of shifting domestic habitudes. Meanwhile, Chance’s three human-sized quilted works concentrate the diurnal process of hand felting, physically instantiating the conditions of labor-time through the slow enmeshment of wool fibers. Imbuing the warp and weft of craft histories of the American South, the wet and needle felted fabrics express densely-detailed abstractions of color. Both practices reflect and manifest unique ancestral notions of the potlach, as spiritual provisions to defer wealth for a future time, and the contingencies of nascent formats resident in the shade of domestic habitude.

Kim Farkas, who is a Paris-based artist of Parenaken descent, creates sculptural forms that address the material lives of diasporic communities and the industrialization of ancient rites and heritages. A graduate of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Farkas began his sculptural practice moulding heads in polished resin, germinating his futurist explorations of augmented humanity. Since, Farkas’ future-oriented objects have merged 3D printing techniques with found consumer items, braiding together anachronistic elements. Evoking both organic epiphytic silhouettes and futuristic biomorphic limbs, these corporeal abstractions address the Art Nouveau medium of lithophanes while gesturing towards millennia-long histories of totemic effigies. Constructed from semi-translucent painted resin, the objects project a toxic delicacy. Digested and folded within these forms are vestiges of consumer and ceremonial items: mahjong tiles, reiki stones and joss papers depicting watches, electronics, and banknotes intended to be burned as offerings for ancestors—at once a poetic signifier of capital’s flow into unseen realms and an acknowledged deferral of material security for immigrant communities.

Farkas’ sculptures invite nuanced discovery and introspection, suggesting how the production of Southeast Asian economic goods reflect both specific identities and religious practices as they do an industrialized global supply chain, gesturing – broadly – to a composite humanity enveloped in machinic revolution, and – specifically – to the proliferation of what the artist labels as a coordinated “Chinatown aesthetics.” In this sense, Farkas skillfully foregrounds both his cultural heritage and Parisian artistic context into critical constellation.

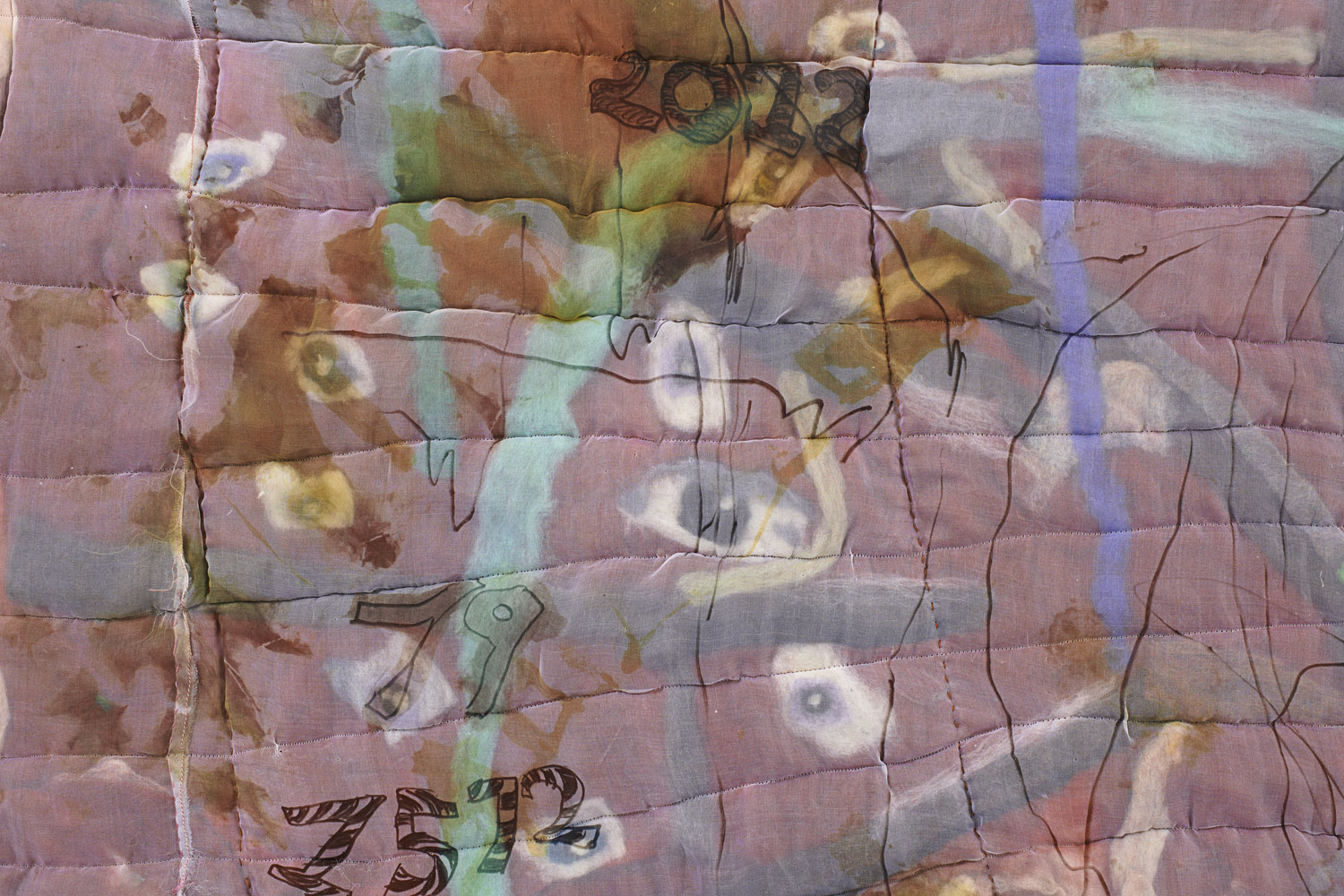

Closer to home, quilt-making responds to domestic forms of familial bequeathment, gesturing to the transfer of spiritual wealth. The works that comprise Justin Chance’s multivalent sculptural practice almost always seem impossible to reverse engineer, regardless of whether the objects in question appear as material studies—unfurling garlands of shag, delicately rendered fragments of lace, “flooded basement papier-mâché,” pre-owned electric fans retrofitted with mossy carpeting, and, particularly, the quilt-like wall works constructed from felted wool encased in silk organza for which he has become increasingly known. Here, Hamlet (2021-22) exemplifies Chance’s quilted composition, oscillating wildly between playful representation and pure abstraction—alluding to and manifesting processes of cross-pollination, sedimentary formation, and natural erosion. In History (2021-22), seemingly arbitrary dates are scrawled across the organza encasing, appearing as a palimpsest of historical events domesticating time. The depths of Chance’s meticulous engagement with organic matter—silk, wool, cotton, tobacco and tea leaves, to name a few recurrent choices—similarly soak up the charged material that point to histories of global trade.

“The origin and essence of our wealth are given in the radiation of the sun, which dispenses energy — wealth — without any return. The sun gives without ever receiving.” Writing on the expenditure of excess energy, Georges Bataille equates the sun as the original gift giver. The solar economy, in which all activity on our globe derives, eventually restores all wealth to its original function: “[…] to gift-giving, to squandering without reciprocation,” to the froth and protracted frenzies of luxuries, war, and inflation. The works in this exhibition by Farkas and Chance shore up vestiges of wealth, totems of the perceptual flows that accompany a spiritual harvesting of the sun.