In her landmark study of painting in the 17th century Dutch Republic[i], art historian Svetlana Alpers argued that this was fundamentally an art of description, in contrast to the Italian tendency towards narrative. Dutch artists “present their pictures as describing the world seen rather than as imitations of significant human actions”; in their hands, an emphasis on painting as craft fuses with a broader cultural fascination with the observation of the natural world, aided by advances in the science and technology of optics. To paint the world was to know the world—and also to reflect on the artist’s own role in its framing.

Looking at the work of Stephanie Hier, her engagement with the Dutch tradition is evident, not least on the level of technique: she began studying at a classical painting atelier at a young age, where she learned to build a realist picture in the manner of the Old Masters. The paintings in Part and Parcel likewise display any number of genre scene standards—piled oyster shells, fruit, flowers—whose meticulous rendering might be taken as an implicit riposte to the recent dominance of intentionally deskilled approaches to painting. But Hier is far from a pre-modern throwback: instead, her work considers the place of painting—figurative painting, in particular—in a world defined by the rapid proliferation of digital images circulating at a speed and scale that would have been unimaginable to the likes of Rembrandt and Vermeer.

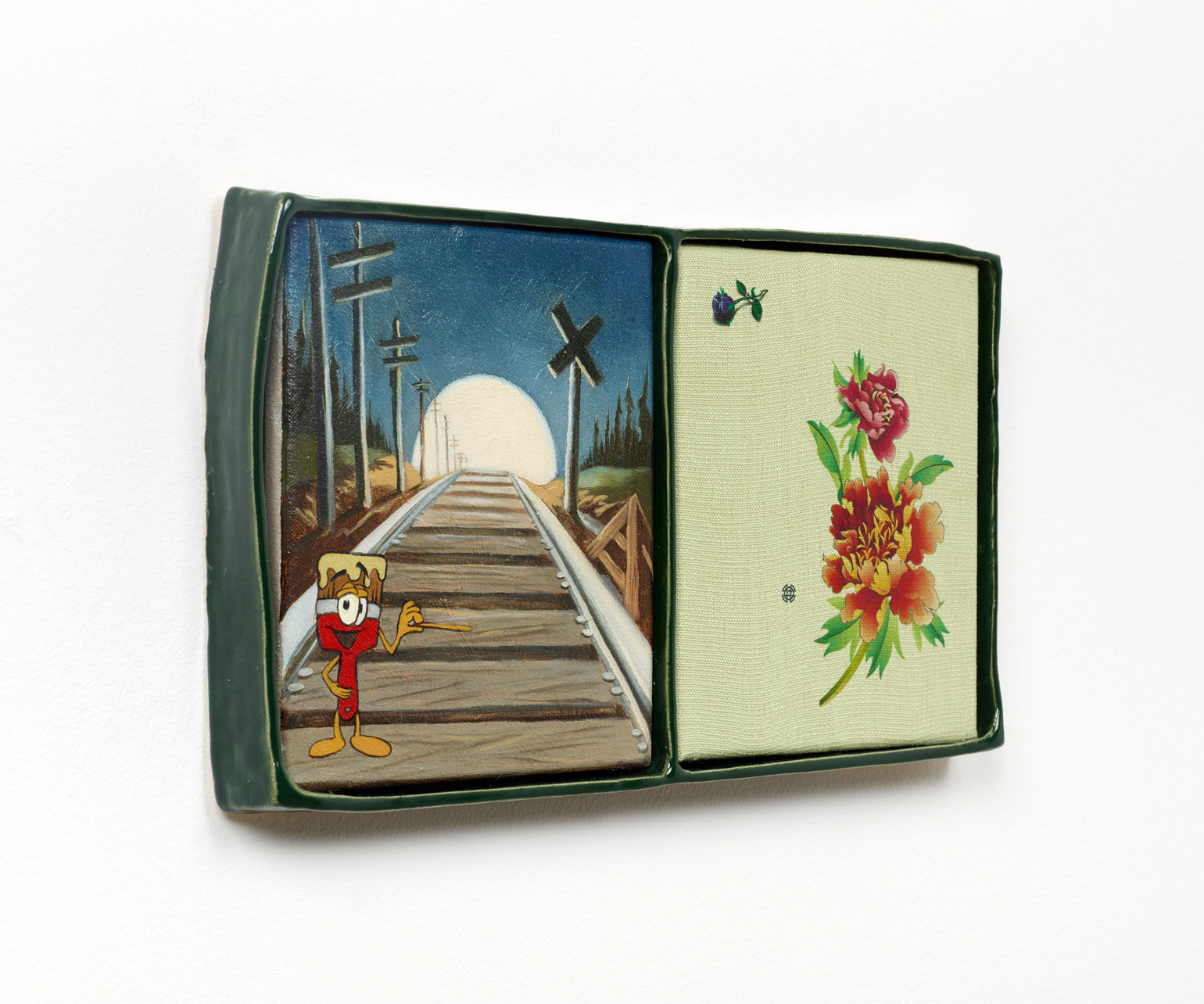

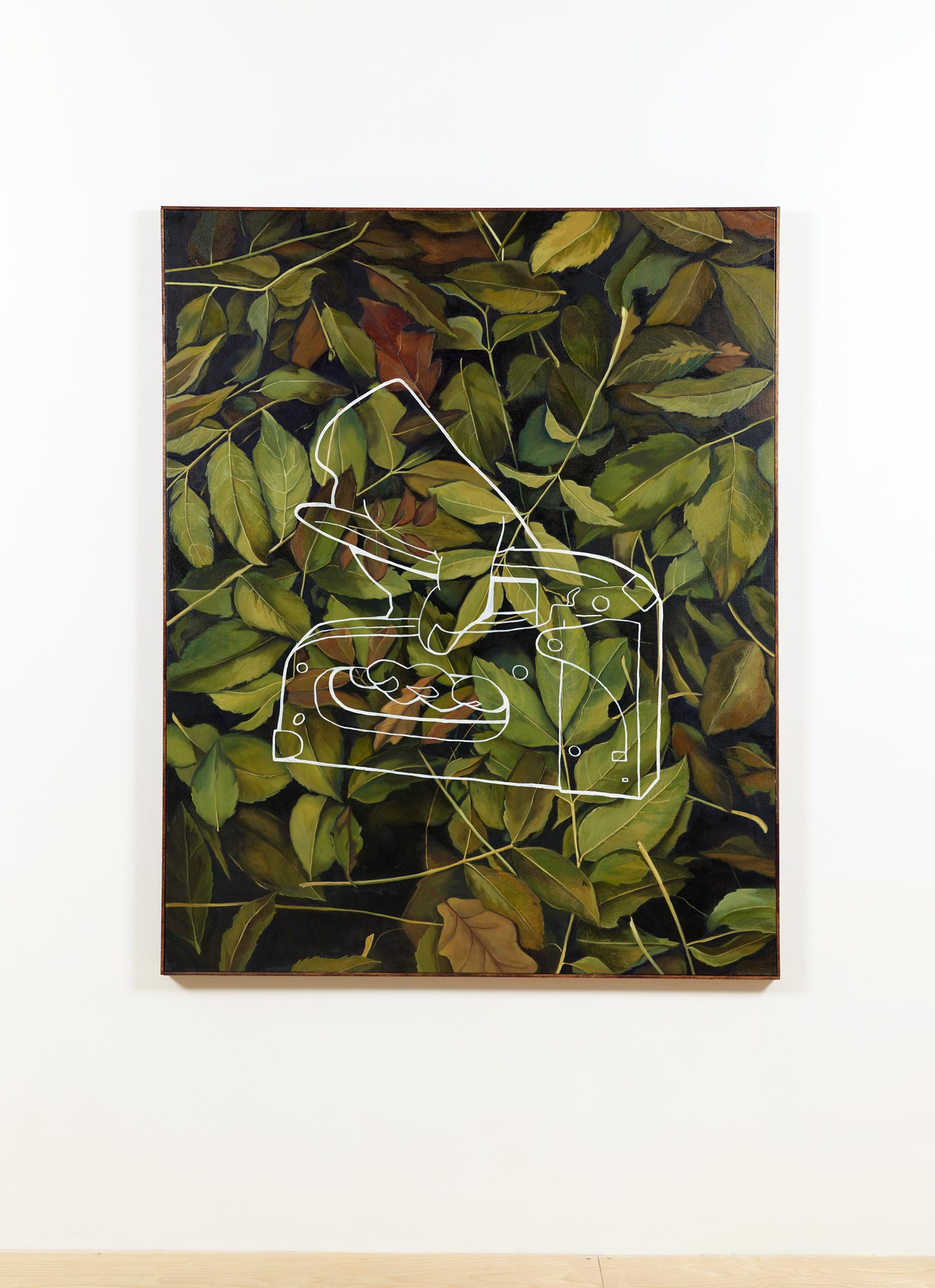

For Hier, the painter is both a maker and a mediator of images. Hence, the works in this exhibition repeatedly return to themes of handcraft and consumption. A pair of large canvases, Hardly Feel Like a Mustard Seed and Light Green Fellow, is emblematic. In the former, the stark black outline of a hand holding a wrench encloses a view of a young woman at the wheel throwing ceramics, a medium that Hier often uses to create sculptural frames for her smaller canvases. The latter painting sets a tabletop still life of overflowing bowls of ripe fruit within the outlines of hands grasping an open book and reading glasses. In employing hands as a literal frame for the painted image, Hier of course plays with the privileged notion of the ‘hand of the artist’ as a metonym for the artist’s unique painterly signature. But she also suggests that the painter’s task is less a matter of depicting the world than framing and reframing it, slowing down the flow of images that surrounds us so that we might engage with them more critically. Hier’s handmade ceramic frames function similarly, emphasizing the extent to which crafting an image and framing it are inextricably linked within her practice.

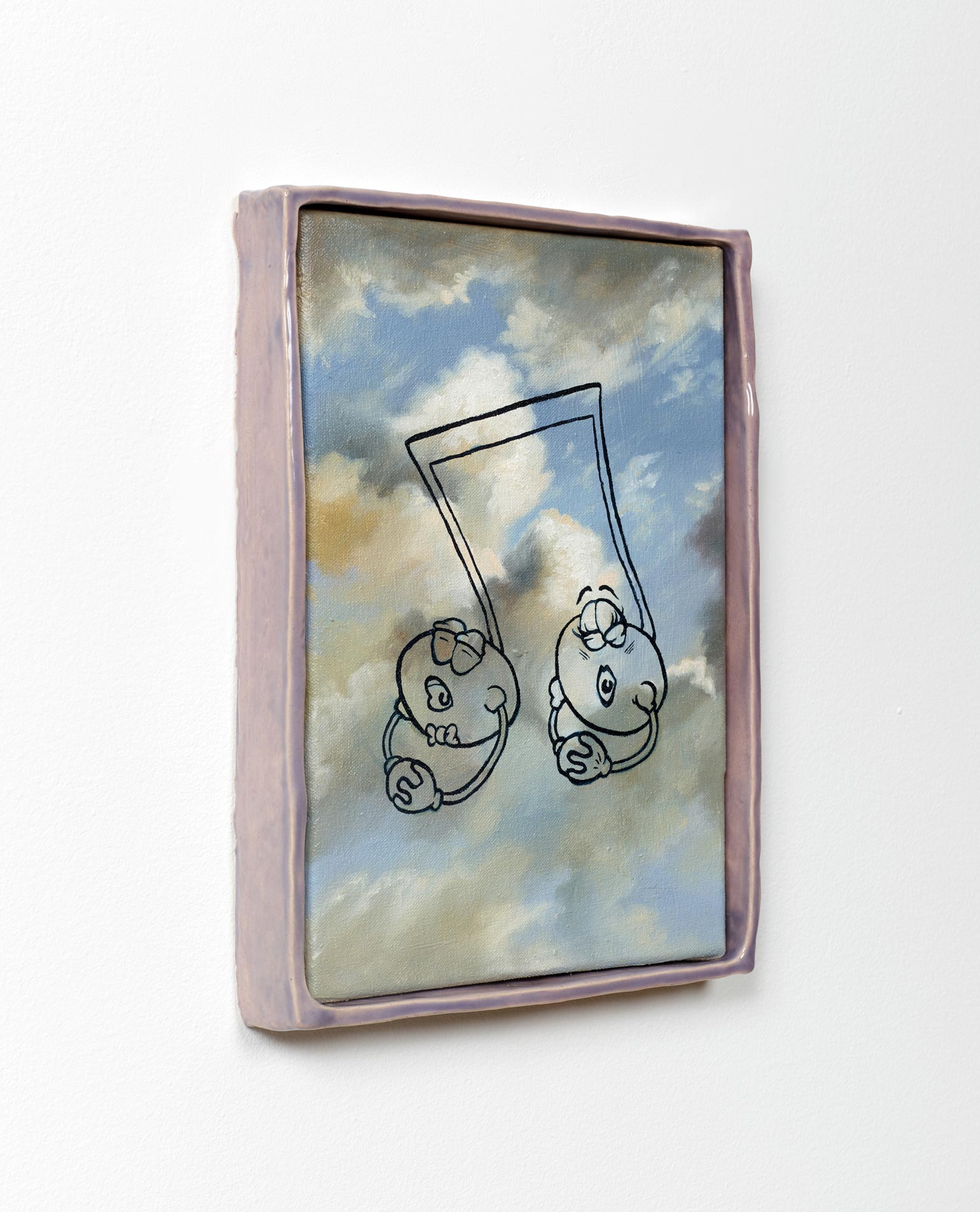

It’s worth noting, though, that the hands framing these paintings aren’t entirely Hier’s own: they are readymade images, taken from the artist Tom Tierney’s extensive catalogue of proto-open-source “ready-to-use” illustrations—the original clip art—which he began publishing in the mid 20th century. Hier’s paintings routinely stage this sort of confrontation between seemingly incongruous representational systems within a single picture; perhaps ironically, it might be described as her artistic signature. Alongside areas of precise painterly realism, Hier often draws on the aesthetics of early cartoon animation, particularly the style of Preston Blair, a Disney animator in the 1930s who went on to author a series of influential how-to books. To this she adds another pseudo-readymade layer in the form of the paintings’ titles, often derived from song lyrics, quotes, and snippets of overheard dialogue. In Bits of Business, a cartoonish outline of a sulking figure with a comically oversized dripping paintbrush is superimposed over a luminous, painstaking rendering of a Eulophia orchid’s drooping buds; in Waltz for a Spaniel, a small, timeless cloud study provides the backdrop for anthropomorphized musical notes, shown clasping their hands together and singing. These juxtapositions are dissonant in technique and tone, but Hier isn’t going for mere shock value; instead, she mines the associative logic of contemporary visual culture, in which the most stylistically heterogeneous images routinely coexist side by side according to the whims of an algorithm.

[i] Alpers, Svetlana. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1983