From our current perspective, Hollywood’s blonde heroines are always coming of age for the wrong reasons. A SoCal sorority sister enrolls in Harvard Law intent on winning back her WASP-y ex-boyfriend; or a showgirl from Little Rock stages a successful revue in Paris while otherwise engaged in a comically pathological pursuit of diamonds; or, maybe, a blindly ambitious news personality attempts to boost her ratings, and, instead, tumbles down the nationally-syndicated rabbit hole. “Wait, am I gonna be the story?,” asks Charlize Theron anxiously, portraying a fellow blonde, former Fox News host Megyn Kelly, early in Jay Roach’s 2019 film Bombshell, a political comedy documenting the proto-#MeToo demise of the cable network’s mastermind Roger Ailes. Set against the backdrop of the 2016 presidential election, the film introduces a Queen of Hearts: then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, who orders Kelly’s decapitation by mean tweet, for Kelly’s crime of confronting Trump with a headline-grabbing account of his own misogyny on live television. Most viewers of Bombshell will arrive to it already knowing what comes next: Fox’s subsequent embrace of Trump and desertion of Kelly, former host Gretchen Carlson’s wrongful termination suit against the network, the seemingly endless, sordid accounts of sexual harassment at Fox that followed, and, in the final act, Kelly’s career-defining patricide of Ailes, her Jabberwock-like mentor. Replacing the real world leads with A-list actors like Theron and Nicole Kidman, the film draws our attention to the uncanny construction of its own image, and, perhaps inadvertently, the plasticity of its main subjects. And, as evinced by the duality of its title, Bombshell shares with Ailes an understanding that his deleterious production of “the story” and his manufacture of the telegenic personality are irretrievably, inextricably connected.

The film is the subject of Jacqueline Fraser’s The Making of Bombshell, 2021, the latest entry in a series of installations, beginning with The Making of La Dolce Vita, 2011, and including recent iterations The Making of Dressed to Kill, 2019, and The Making of Maria by Callas, 2020. Drawing upon the title format of the behind-the-scenes documentary, generally released alongside the film as a sort of fan service or promotional tool, Fraser retains the parallelism of the format, but inversely imagines herself to engage in a process of remaking the source film through a series of collages and assemblages, later installed alongside an unadulterated projection of the film. Like Bombshell, the films Fraser selects almost always seem self-reflexively concerned with their own production, and, for that reason, often revolve around media narratives, be they born from rote genres like the newsroom procedural or the biopic, or, alternatively, the auteurist modalities of Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini. Just as these source films run the gamut from the new wave of yesteryear to the in-flight entertainments of today, the recurrent materials in Fraser’s arsenal may include both designer dresses and dollar-store party supplies, though the artist tends to favor the latter, particularly those that bear a mimetic relationship to signifiers of wealth: the metallic and jewel-toned surfaces of tinsel curtains and sheets of gold foil, for example, or the occasionally convincing imitation, like faux fur and costume jewelry.

Indeed, it is in large part this connection between commonplace costume jewelry and the on-set costume department that animates these works, particularly the suite of assemblages that form outfits without bodies: tops of lace and tulle, dresses cut from Lurex, sequins on sequins, heels fitted with plastic gems and long satin ribbons, unnaturally white wigs. These shimmering looks hang against the wall, slightly above eye-height, as they might in a dressing room, each adorned by a descending column of printed images, one that suggests a sort of film strip unspooled vertically – an association seemingly confirmed by their sequential use of repeating images, torn from fashion magazines like i-D and Vogue Italia. Similarly editorialized images of pin-ups, garments, and interiors predominate a nearby series of collages mounted on embroidered sheer fabrics and corflute. Reminiscent of both teen bedroom design and pitch meeting mood-board, her collages function synecdochally to the installation as a whole, which is to say, less as movie fan-fiction and more as a breadcrumb trail leading us toward the dream factory of Fraser’s own design.

The artist’s Making of Bombshell appears in Legally Blonde, Downs & Ross’ inaugural group exhibition of the year, alongside works by Vikky Alexander, Darja Bajagić, Marie Karlsberg, Catherine Mulligan, and Kayode Ojo. As does Fraser’s installation, the exhibition locates the making, unmaking, and remaking of the commercial image in the broader cultural representation of blondeness , a tradition particularly relevant to cinema at least as early as Jean Harlow’s performance in Platinum Blonde, 1931. Harlow’s weekly application of coloring agents–a noxious mixture of peroxide, ammonia, Clorox, and soap flakes, held in secret measure–to maintain her platinum image may point analogically to a mode of production scrutinized here, as well as to the extremities undergirding the commercial image at large. Yet if many of the works on view appropriate visual matter from elsewhere, they do so following the somersaulting example set by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, the classic noir in which Kim Novak plays the blonde Madeleine, who may be possessed by the spirit of her blonde great-grandmother Carlotta, but instead turns out to be brunette Judy, who is then made again into an ersatz Madeleine, compliments of a new wardrobe and, of course, a bottle of hair dye. Or, perhaps, the aggregation of these works departs from the complex web of associations spun by the deceptively simple phrase “legally blonde,” which the exhibition borrows from the 2001 Reese Witherspoon vehicle: maintaining the jokey, willing conflation of hair tone and visual impairment, the sort that could rob Witherspoon’s Elle Woods of her Porsche Boxster, but also the close proximity between the knowing performance of the “dumb blonde,” and the morally-evasive connotations of the legal term “willful blindness.” Ojo’s new works on view pose a direct response to this film, while simultaneously making wider reference to the artist’s practice, which, like Fraser’s, often takes a film as its initial point of departure. Quite literally in the case of And Scented, 2022, in which the artist presents stacks of his own CV printed on blushy-sheets of printer paper compartmentalized into a series of glass trays, transforming Elle Woods’ pink resume faux pas into an elegant rendition of professional striving. Ojo’s Study for Shattered and Undressed (Hilton), both 2022, extend strategies of readymade assemblage the artist has developed previously, cultivating singular forms from hyper-specific commercial and industrial products, and subjugating them, here, to the logic of Legally Blonde.

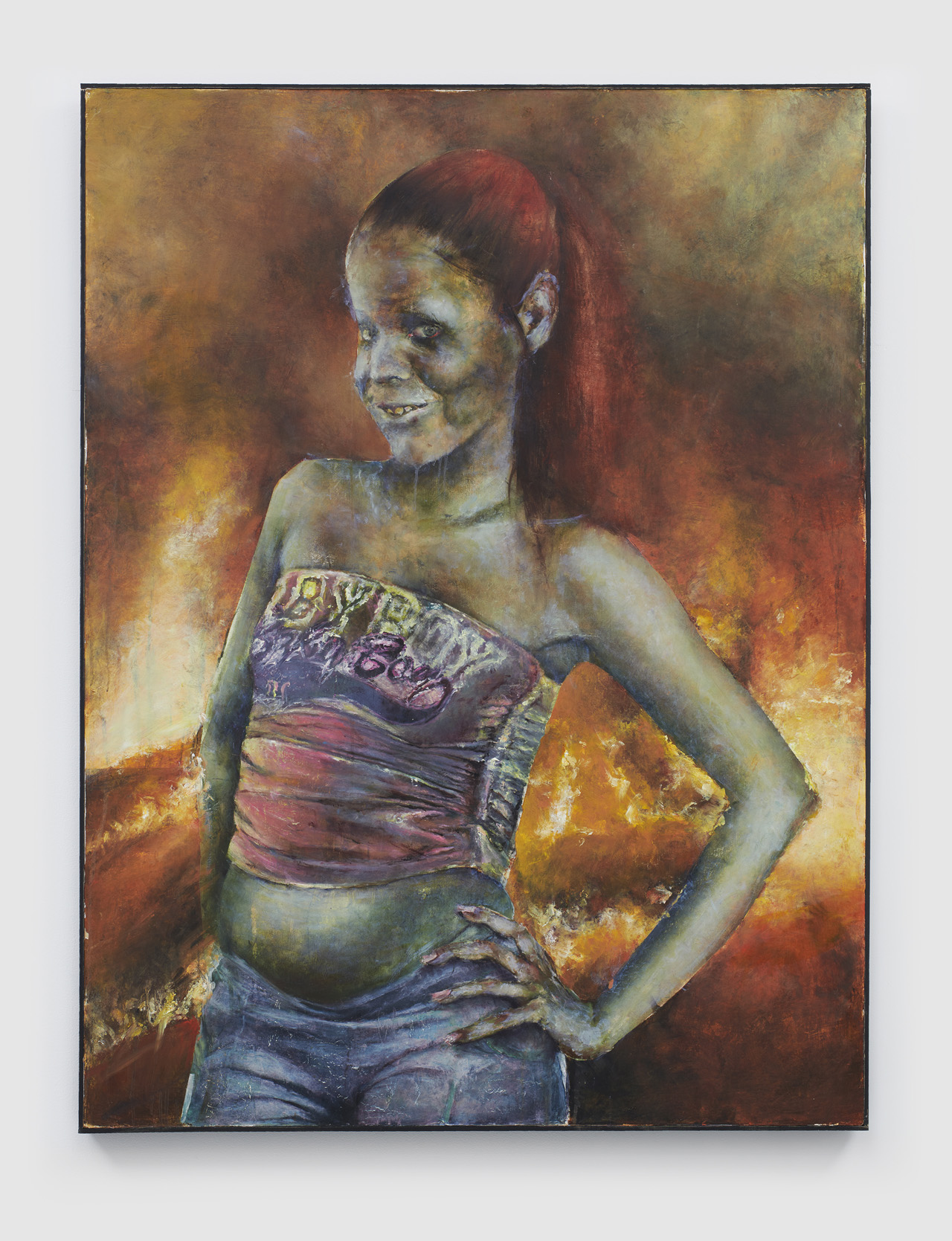

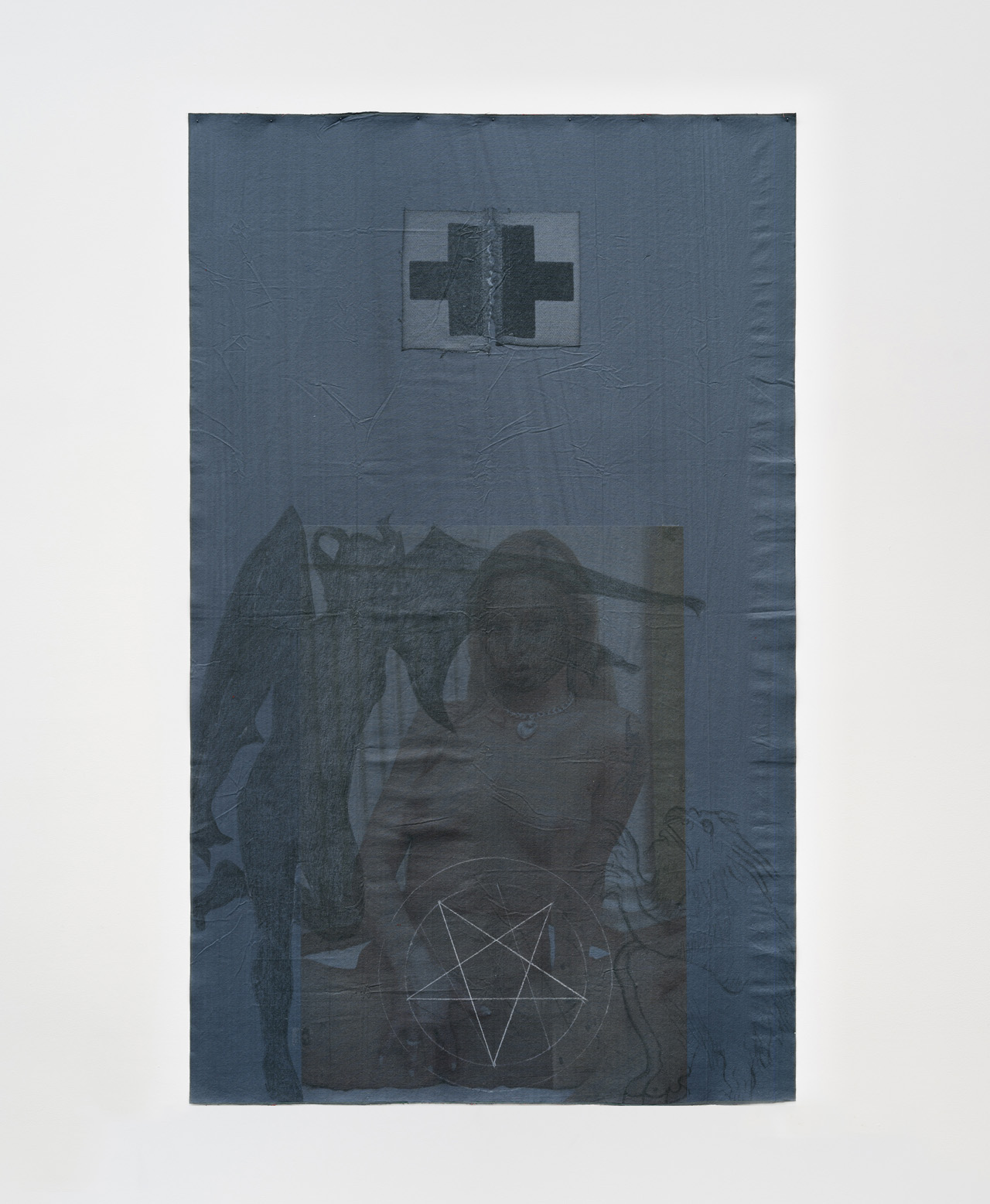

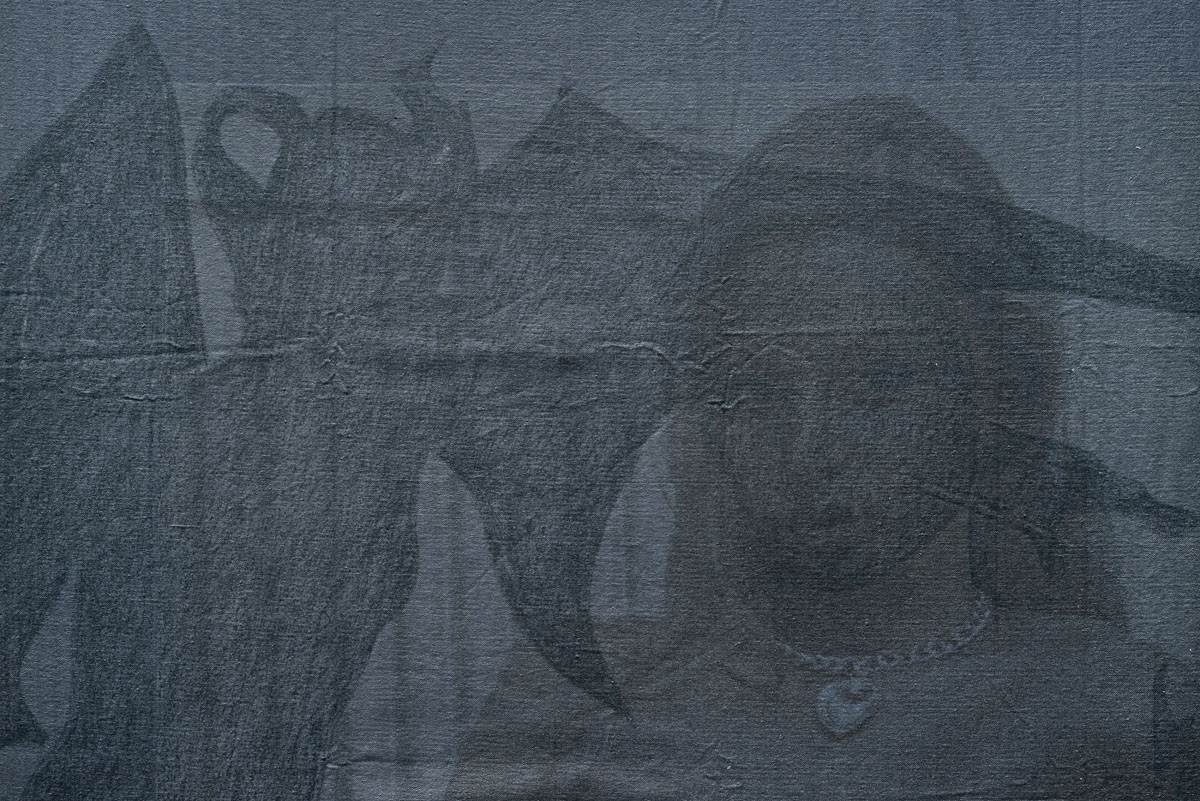

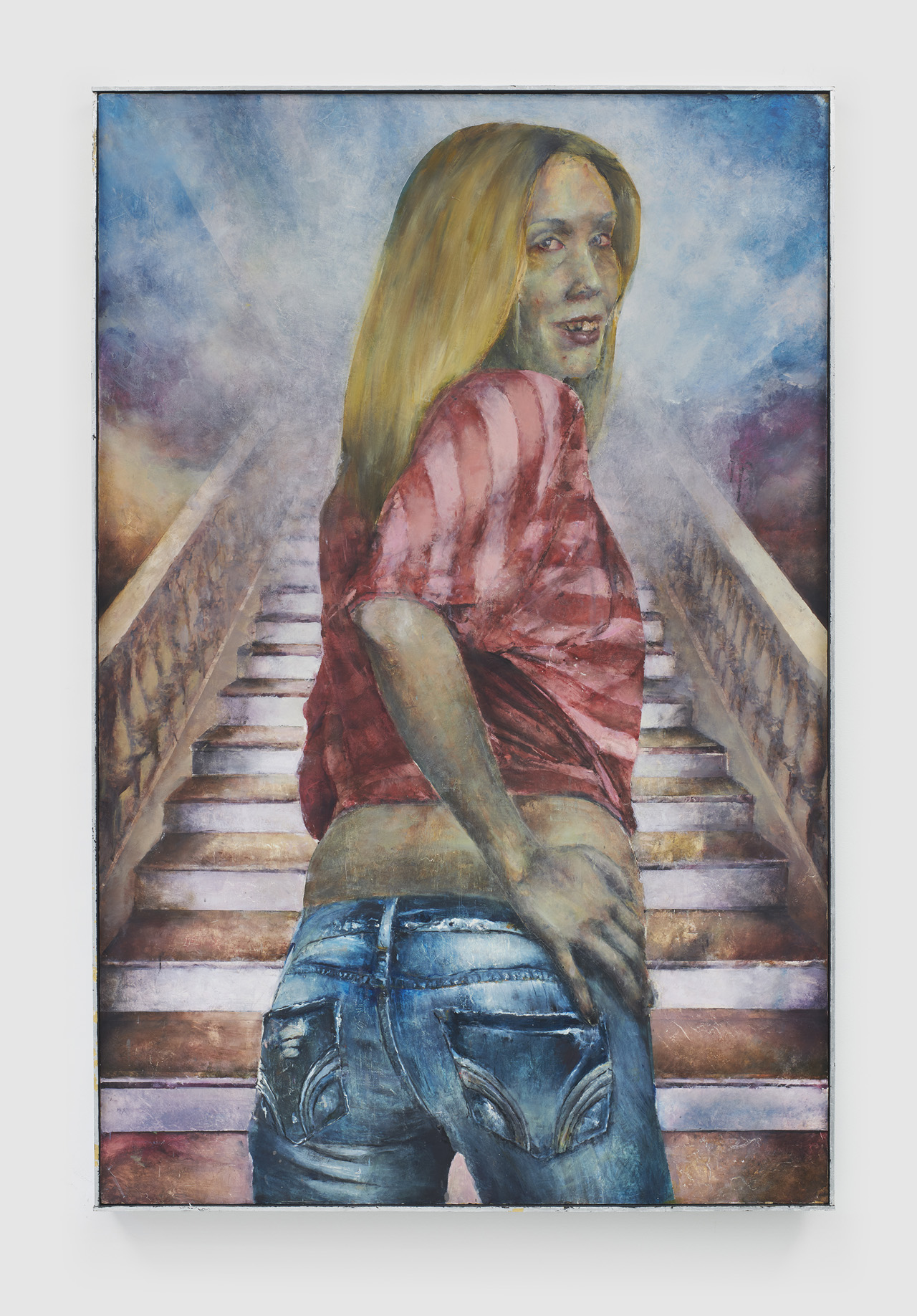

This critical reimagining arrives just as the blonde cipher disappears from the scene, and just as the last scene’s most prominent fixtures, those circa Legally Blonde, undergo a sympathetic narrative revision, one spurred by made-for-streaming docs like Framing Britney Spears, 2021, and This is Paris, 2020. Perhaps that’s why there’s something of The Simple Life in Catherine Mulligan’s tragicomic paintings of the undead – Angel 1, Angel 2, and Devil 1 – all midriff-baring and denim-clad, in the form of low-rise jeans or distressed mini-skirts, recalling in dress and demeanor the early-aughts tabloid reign of Britney and Paris, or, perhaps more precisely, the non-mononymous creatures who slinked through early reality shows like Laguna Beach and The Hills. Darja Bajagić likewise extends this meditation on the relationship between violence and media representation, in a large work on canvas, entitled “Nadryv.” This untranslatable term, integral to Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, suggests that the blonde subject of Bajagić’s piece is experiencing a violent outburst, while alluding on the formal level to a seemingly Fontana-esque tear in the canvas, one which fails to materialize.

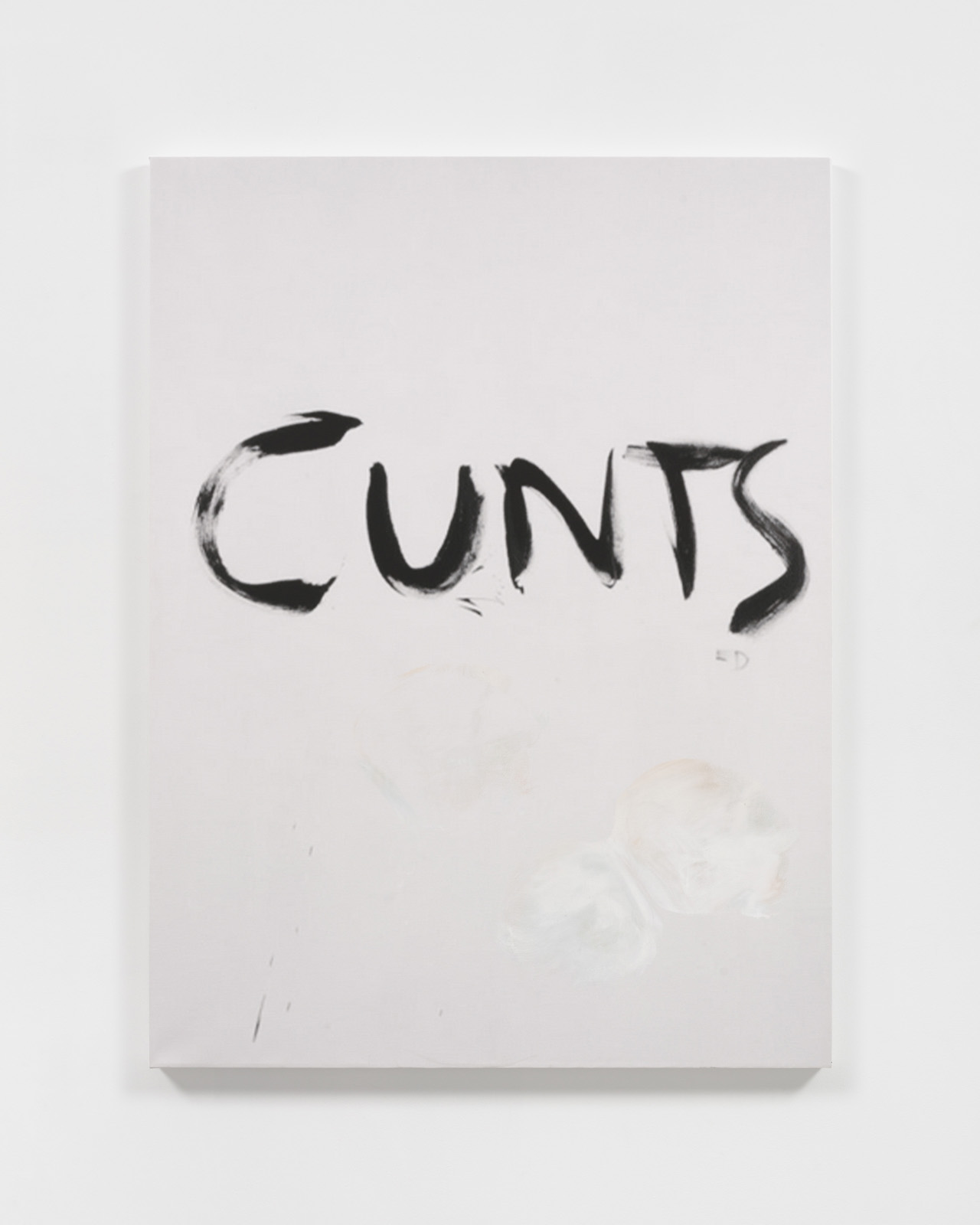

Elsewhere, Marie Karlberg constructs desecrated copies of works by cool male conceptual painters who came to prominence in the late 1990’s, artists like Merlin Carpenter, Günther Förg, Christopher Wool, and Heimo Zobernig. Transforming the painterly surface of the original into a digital image and then printing it back onto canvas, Karlberg allegorically submits her source material to a sort of blonde-ification, while simultaneously restoring her own authorial signature by repetitiously applying her own ass to canvas, covered in gouache. By employing herself in a performance redolent of Yves Klein, Karlberg humorously suggests a psychosexual relationship to this lineage of intellectual bad boys turned art market mainstays, tempered by a self-reflexive knowingness that resonates not only elsewhere in her oeuvre, but also in the dually defiant and aspirational logic at work in the exhibition.

These recent works are complemented by Vikky Alexander’s Portrait of Hugh Hefner, 1984, a triptych of the Playboy founder in absentia, suggesting Hefner may be reconstructed from the reproduction of the visages of some of his best-known subjects. The group portrait at hand deploys Alexander’s signature appropriative method of photographing magazine spreads and subjecting the resulting images to a number of analogue editing processes and installation strategies. In this restaging of images, Alexander reclaims a trajectory set forth by Willem de Kooning’s Marilyn Monroe, 1954, a smiling portrait of Hefner’s initial, unwitting subject, and extended memorably by Andy Warhol’s elegiac Marilyn Diptych, 1962, completed soon after the actor’s infamous suicide. The Monroe of Alexander’s triptych is flanked by a late-career subject of Warhol’s, Blondie’s Debbie Harry, as well as Dorothy Stratten, a young centerfold model murdered by her paranoid, estranged manager-cum-husband, months after she was named Playboy’s 1980 Playmate of the Year. If Harry’s inclusion elicits fondness for the self-possessed iconicity garnered by one former Playboy Bunny, the concurrent evocation of Stratten’s short life serves to implicate Hefner and the relentless machinery of image production the publisher put in place. The gaze that meets us here, from beyond the veil, is one that recapitulates the Marilyn myth at breakneck speed, projecting it back into the present.

Three years after Alexander first created her portrait, the critic Thomas Crow’s extraordinary essay “Saturday Disasters: Trace and Reference in Early Warhol” appeared in the May 1987 issue of Art in America, and earns its longstanding appeal, in part, by assiduously detailing Monroe’s cultural migration from “working-class hero,” to subject of “serious art,” not necessarily a triumphant development. “Any complexity of thought or feeling in Warhol’s numerous images of Monroe may, however, be difficult to discern from our present vantage point,” Crow warns. “Not only does the artist’s own myth stand in the way, but the pictures’ seeming acceptance of the reduction of a woman’s identity to a mass-commodity fetish can make the entire series seem a monument to a benighted past or an unrepentant present.” In Portrait of Hugh Hefner, we find a clever rejoinder to Crow’s concern, leveled from the contemporaneous moment. By positioning Warhol and Hefner’s shared subject between Harry and Stratten, Alexander restores Monroe to the indeterminacy of Warhol’s immediate context: somewhere between the eternal salvation proffered by the mass image and the Saturday Disaster invariably wrought by public life. It is here, between fame and infamy, between rom-com Künstlerroman and pulpy true crime, between self-production and contractual obligation, within the ambivalent space brought forth by Alexander’s Monroe, where the playfully unsettled, and judiciously unsettling, works of Legally Blonde reside.