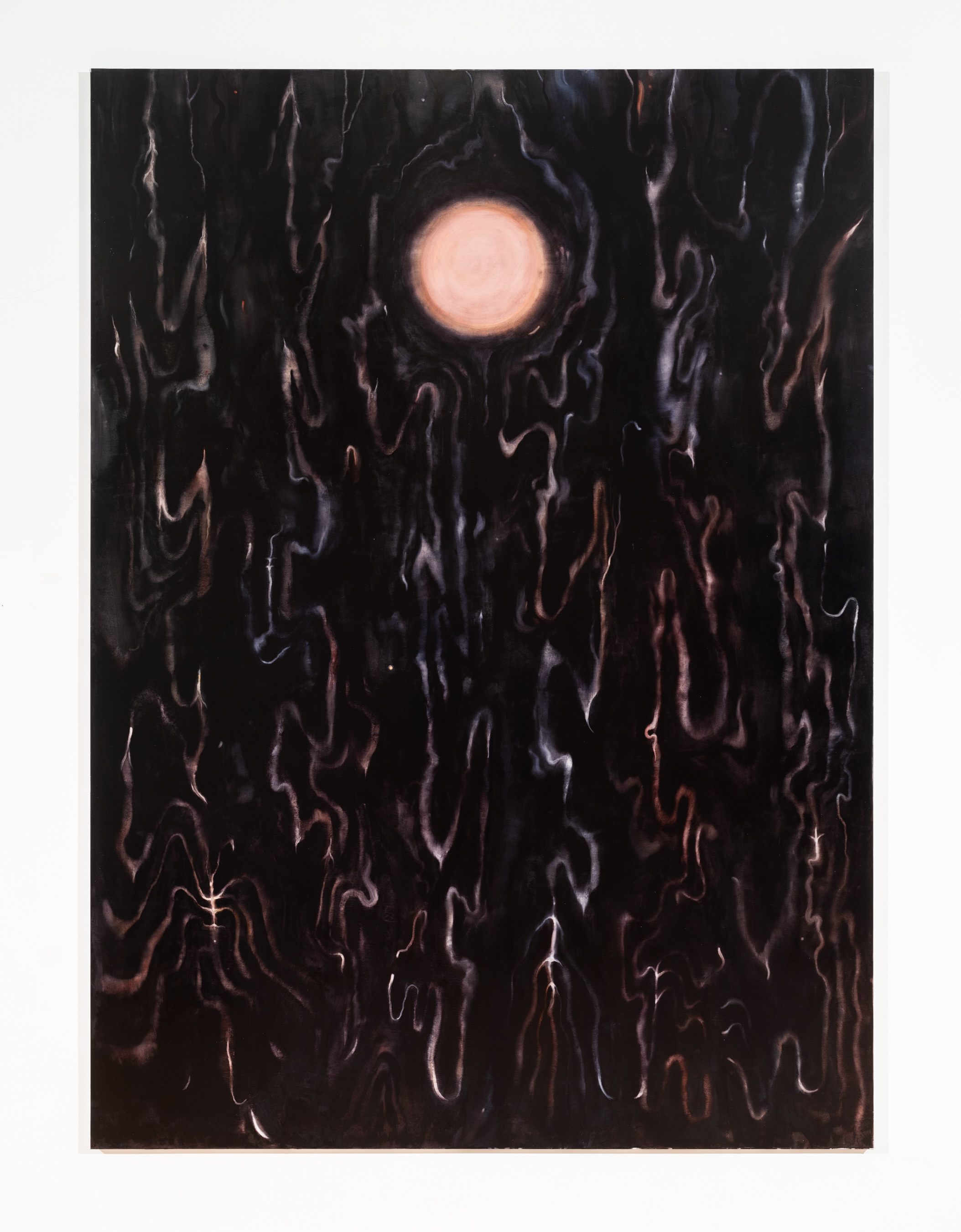

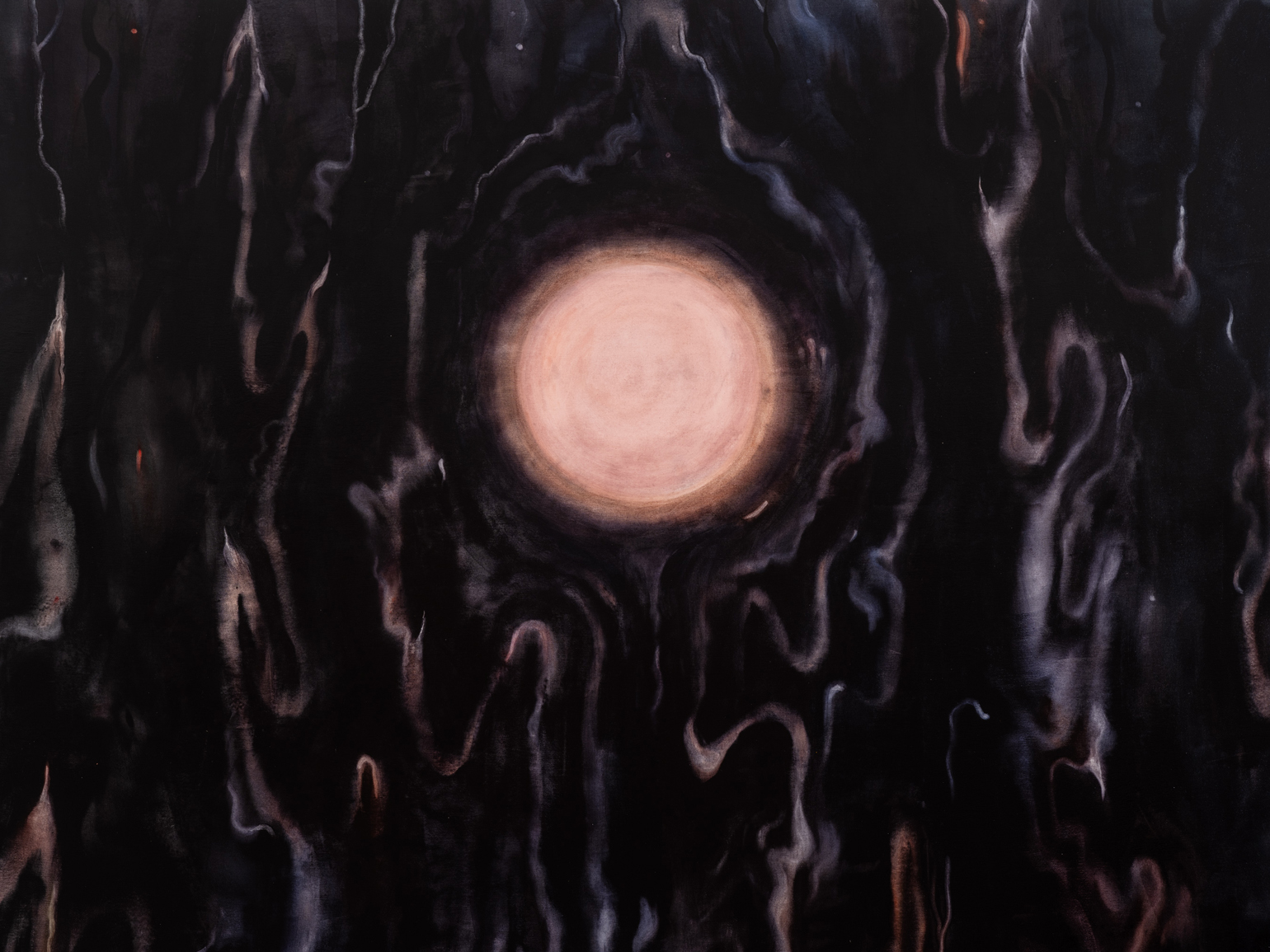

The pitch dark of the painting’s surface, the isolation of the Greek isle upon which the scene is staged, the cluster of elongated trees at the work’s center that, darker still, seem to draw us further into the abyss: taken together these elements form the gestalt of a late nineteenth century painting by the Symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin, Isle of Death, 1880. Occupied by this memorializing commission, the Swiss artist assured his widowed patron that the finished work would be sufficiently transporting. “You will be able to dream yourself into the world of dark shadows,” he promised her. Julia Selin’s first solo exhibition at Tara Downs proffers a similar sensation. The exhibition comprises a suite of four monumental paintings, each much larger than the average human body, and constructs a sort of installation-in-the-round, an encompassing space for contemplation. Drawing on correspondences between the landscape genre and abstraction, paintings such as Sprung out of this world, 2023, tower over us, seemingly ushering us into their depths.

Our relationship to such works as viewers, to their totalizing force, reflects the process by which they were made, the originating haptic encounter between the canvas and the artist herself. Selin covers the canvas in a single layer of dark, nearly black oil paint, a monochromatic coat that slowly reveals modulations in pigment as she works the wet surface with brushes, rubber scrapers, her own hands and fingers. Paint and resin accumulate, ensconcing the artist’s actions as if in amber, and draw attention to the work as a sculptural object in itself. From these simple indexical gestures, Selin conjures both tactile, palpable quality of painting’s earliest origins and the Romantic vestiges of Symbolist painting, evoking a sense of sublimity through the most economical of means.

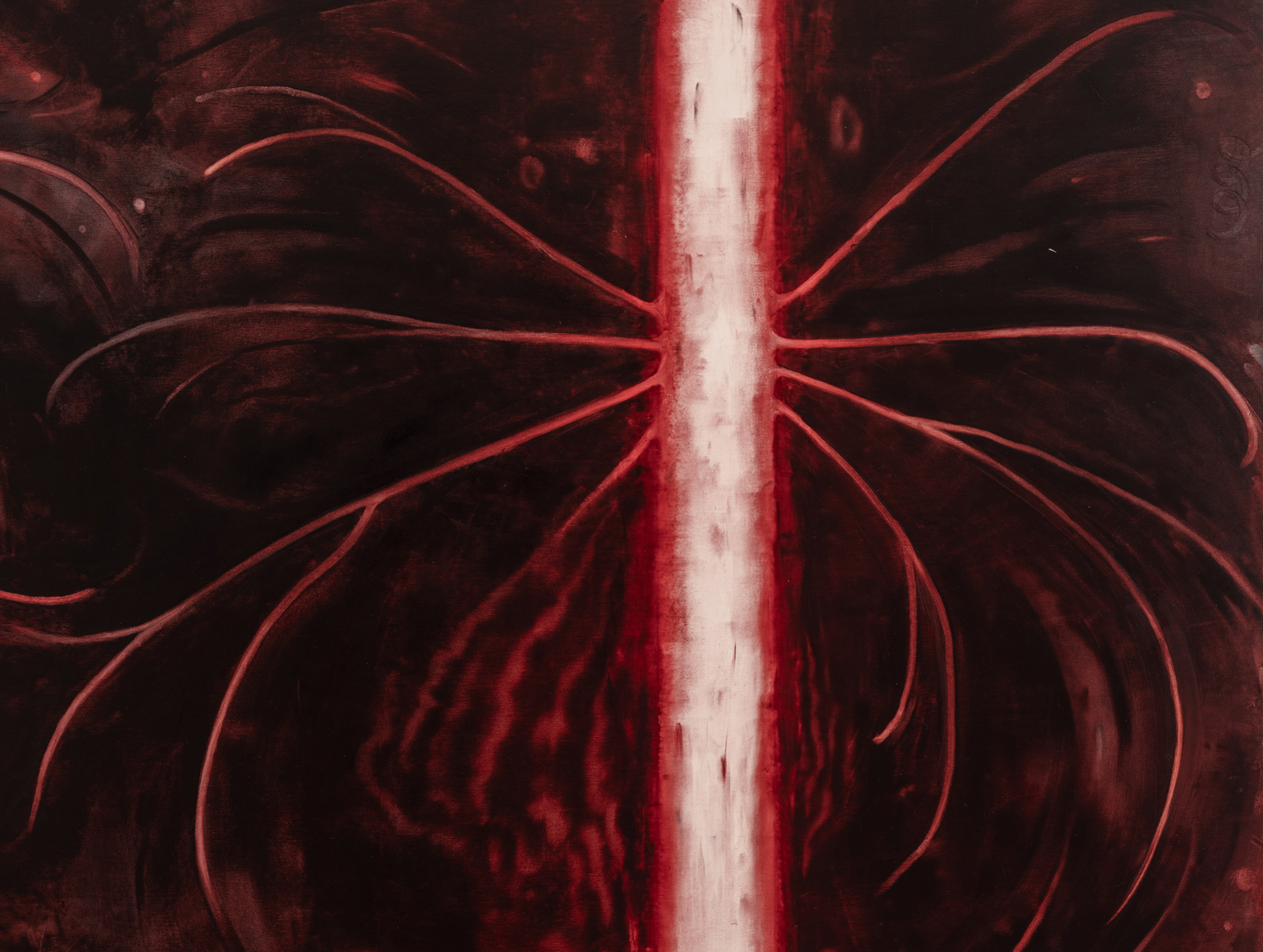

Selin’s preoccupations descend primarily from the Scandinavian tradition, from the thematic concerns of artists like Edvard Munch, Peder Balke, and Akseli Gallen-Kallela, all of whom located contemporary mores and anxieties almost counterintuitively in nature. As demonstrated by works such as Am I mistaking the fluttering moths for a ticking clock, 2022, the artist’s investment is in replicating the more extreme sensory experiences of being in nature – its disorienting effects and awe-inspiring capabilities, while maintaining, like the fin-de-siècle artists who inspire her, a correspondence between landscape painting and deeper existential questions. Her navigation of this correspondence is redolent of the framework first constructed by Wilhelm Worringer’s foundational text Abstraction and Empathy, originally published in 1907. “The need for empathy and the need for abstraction to be the two poles of human artistic experience,” Worringer wrote. “They are antitheses which, in principle, are mutually exclusive. In actual fact, however, the history of art represents an unceasing disputation between the two tendencies.” What’s remarkable about Selin’s paintings is her ability to oscillate between both concepts within the same work, between suggestions of organic identification and self-alienation, or the inner turmoil of the artist, and between the objecthood of the canvas and the picture-window of the works’ surface. Landscape painting is never neutral, and neither is nature, its source material– both are human constructs, culturally determined. Seen from this perspective, Selin’s undulating paintings reflect an ultimately successful struggle to represent both a retreat into the natural world and a fearless confrontation with the contemporary moment.