The revolutionary scientific shifts in eighteenth-century Europe — particularly in biology and geology — were so profound that the ideas they produced have only been expanded upon down to the current day, not overturned. From this era, we inherited the practice of breaking up living things into “kingdoms,” “families,” and “species.” This led to the conviction that life is categorical, and that the categories can be imagined in terms of distance, that is, humans are “closer” to other apes and “farther” from stromatolites. We also learned to think of the planet as impossibly ancient, far surpassing any conceivable point of reference from a human vantage. Following this, the gap between living things and inanimate matter became a chasm, unbridgeable and beyond debate. Time became linear, constantly disappearing behind us and emerging again as we cut a path through it. This intellectual history was liberatory because it helped displace the Bible as the definitive source of information about nature. But it also ushered in a new orthodoxy that has oscillated between dismissiveness and brutality toward animist traditions and people who believe in the spiritual power and inherent value of the other-than-human world.

This exhibition brings together two artists whose photography and sculpture are scientifically heterodox. Dionne Lee and Sarah Rodriguez build upon twentieth-century art historical currents that engage with the natural world, but they also grapple on a philosophical level with the nearly 300-year-old tradition of instrumentalist environmental thought and positivist biology. In their work they challenge us to explore an alternative intellectual history in which human technology alone is no longer the arbiter of landscape art and in which nameless organisms exist that are neither alive nor dead. Both Lee and Rodriguez are keenly interested in what it means to inhabit a place, to engage with the non-human world, and to wrestle with the moral and aesthetic stalemate of the American West. They are part of a generation thinkers who have digested the critiques of scientific dogmatism, American territorialism, and artistic imperialism and have moved beyond the simple rebuttal stage of critique. Instead, they have begun to find inspiration beyond the pale in the uncertain spaces of unfathomable timescales and not-yet-evolved hybrids.

Dionne Lee’s photographs resist easy interpretation. For Lee, the studio and darkroom are not only creative spaces, but also sites of research into both the geologic record and the technology of photography. Her purpose in sorting and rearranging is to nurture new ways of looking and less prescribed ways of knowing, but also to explore meaning in abstraction. She sees a kinship between the fossilized remnants of ancient plants and photographic processes. In this view, fossils are the first photographs, nature’s self-documentation thatpreceded any human apparatus and that are fixed in the original medium—rock. And like fossilization, photographs encode a kind of preservation that is contingent, chemical, a revelation.

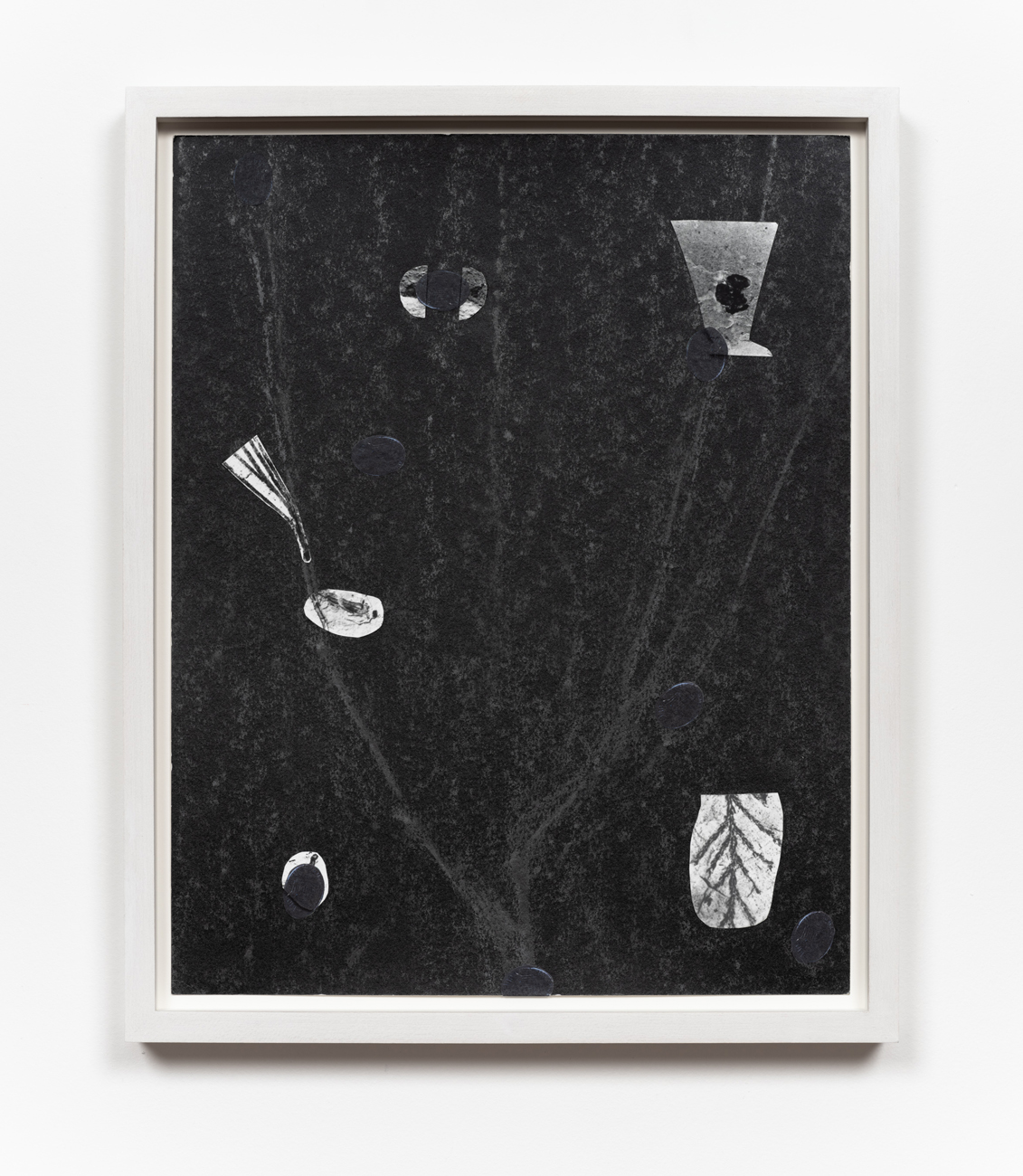

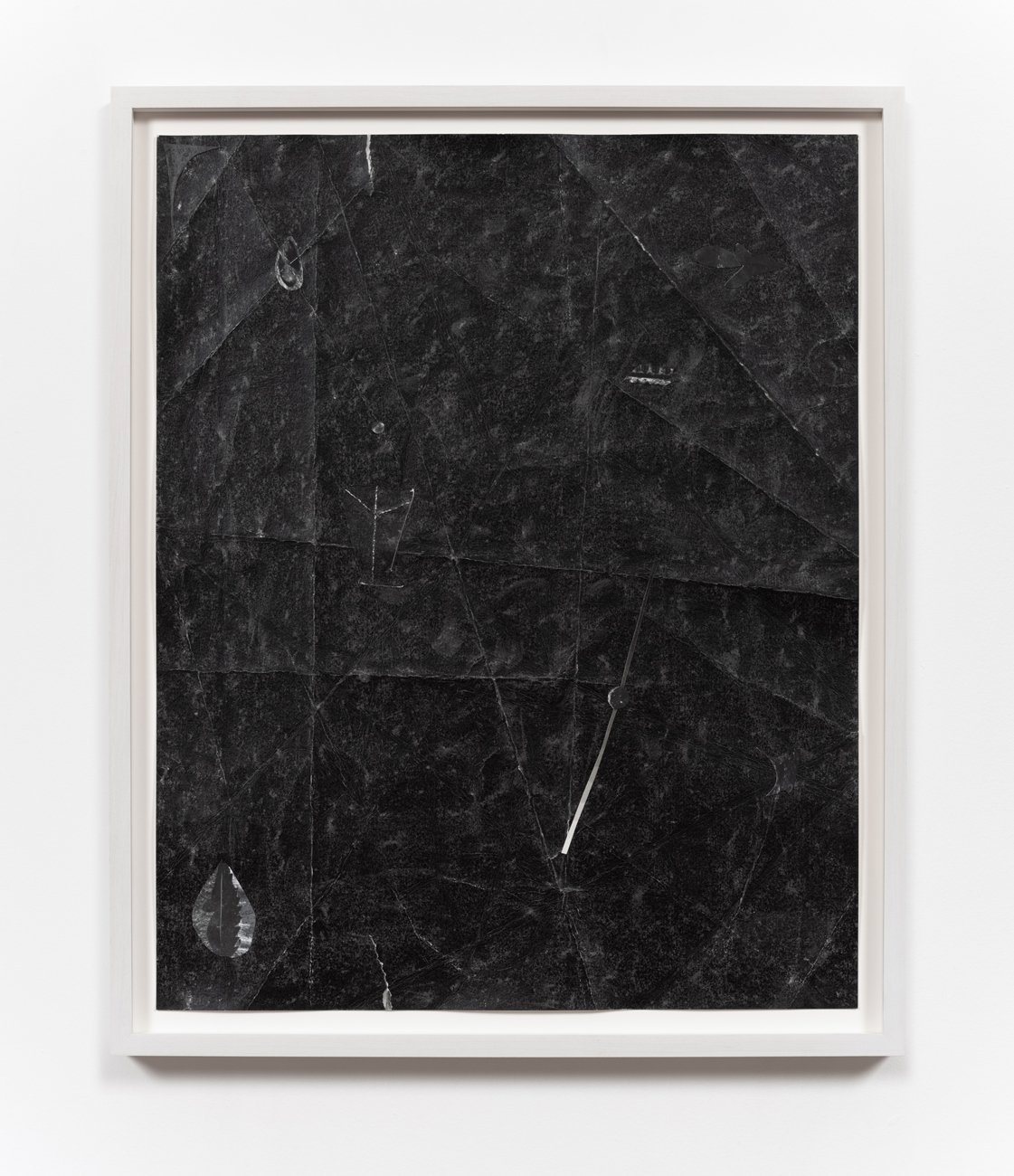

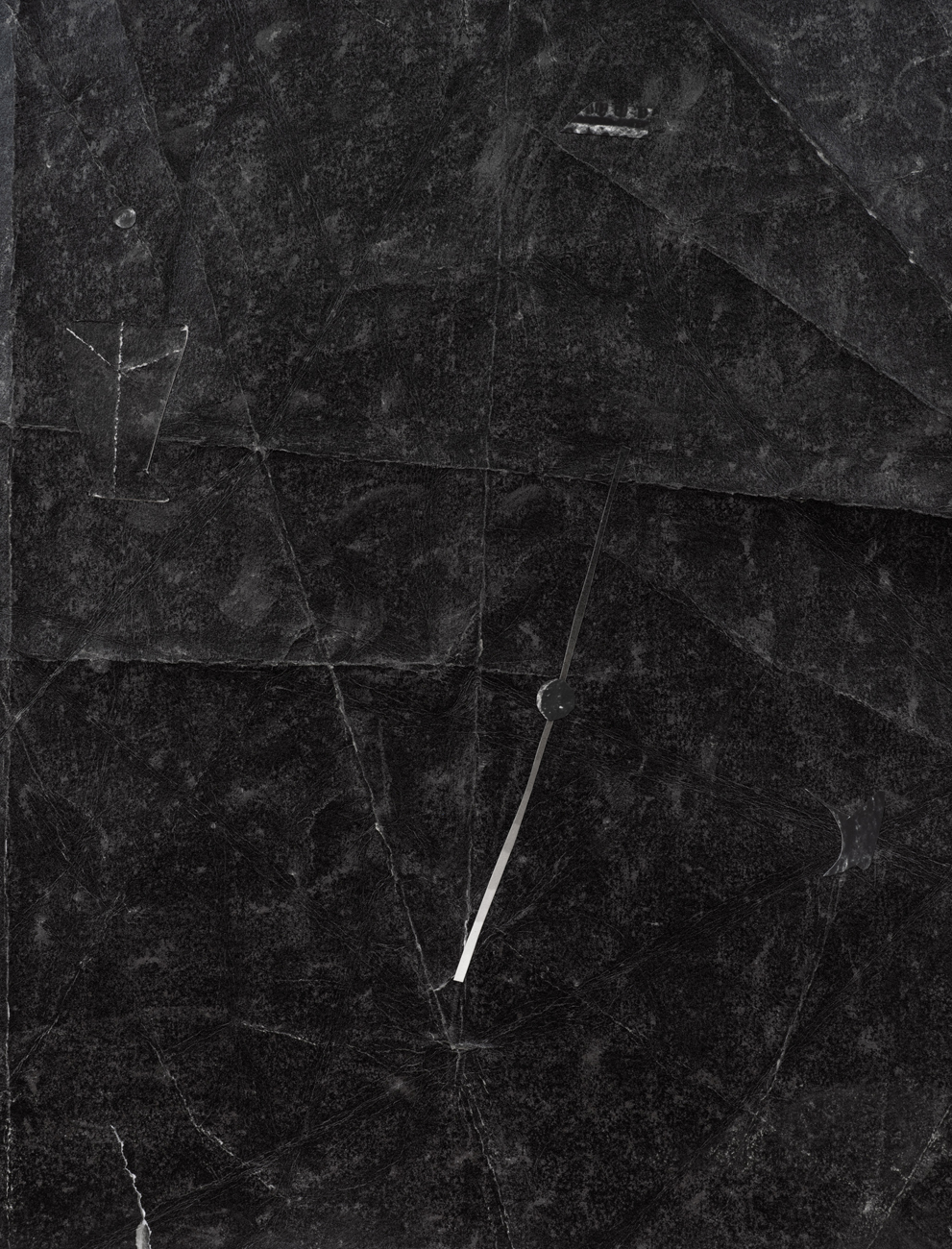

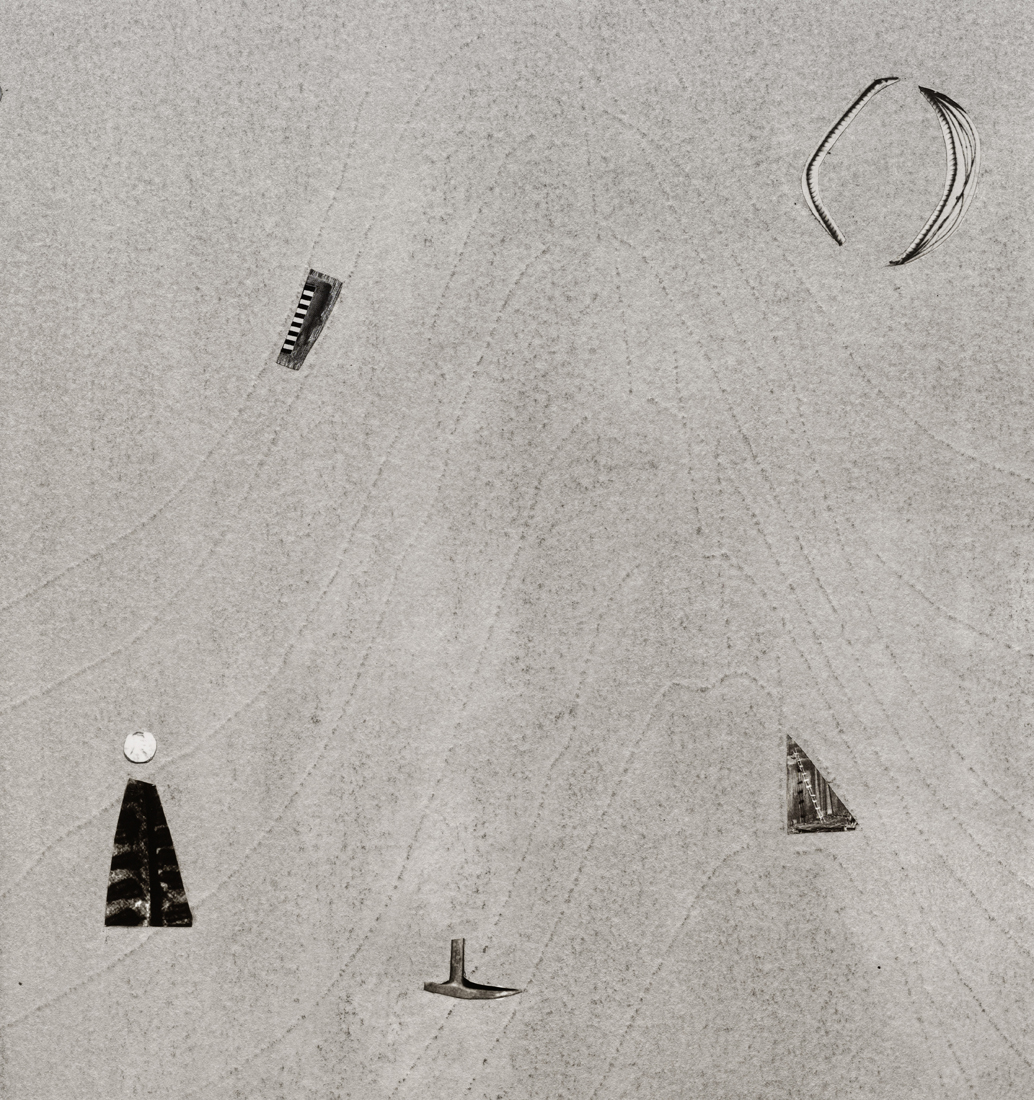

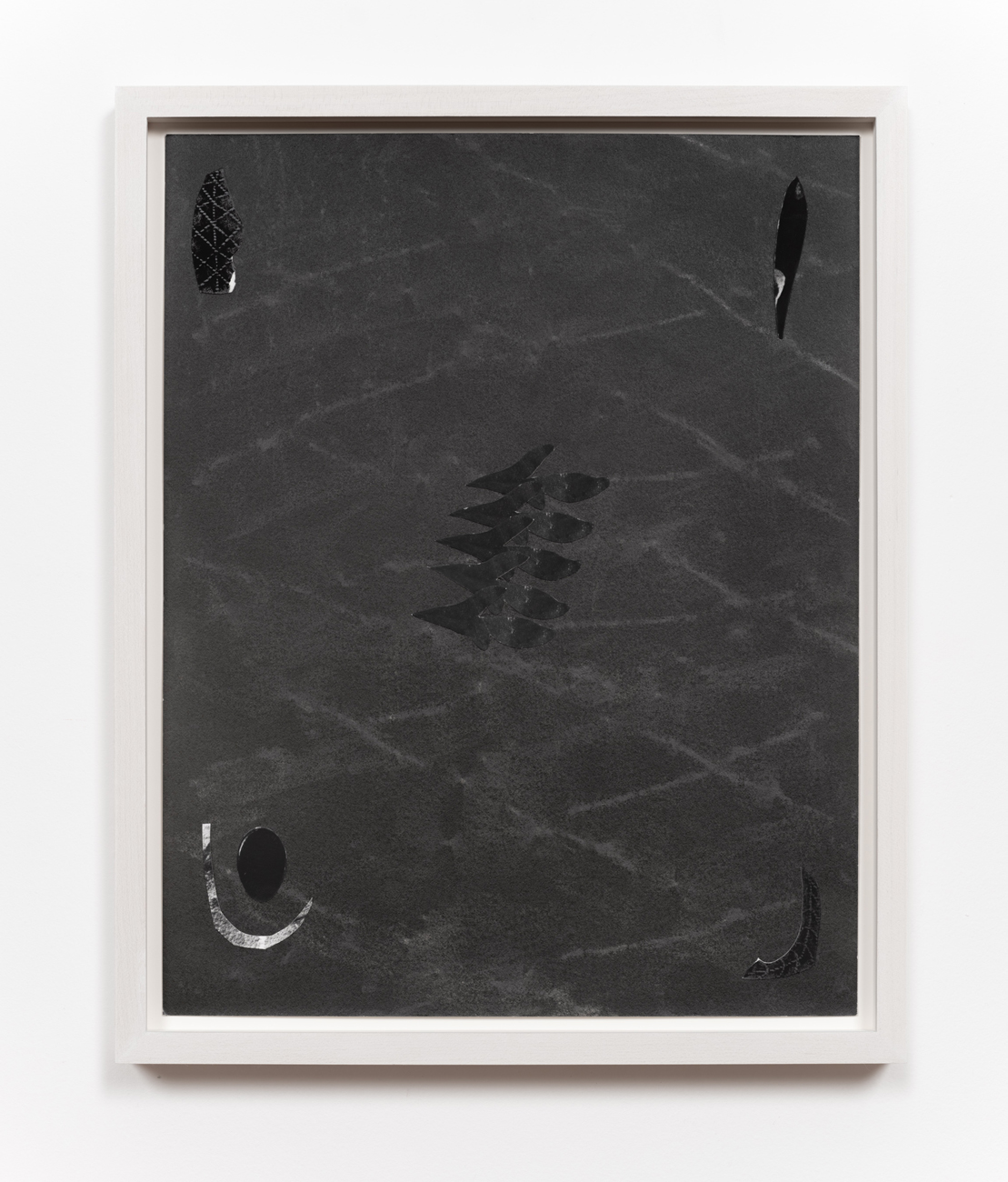

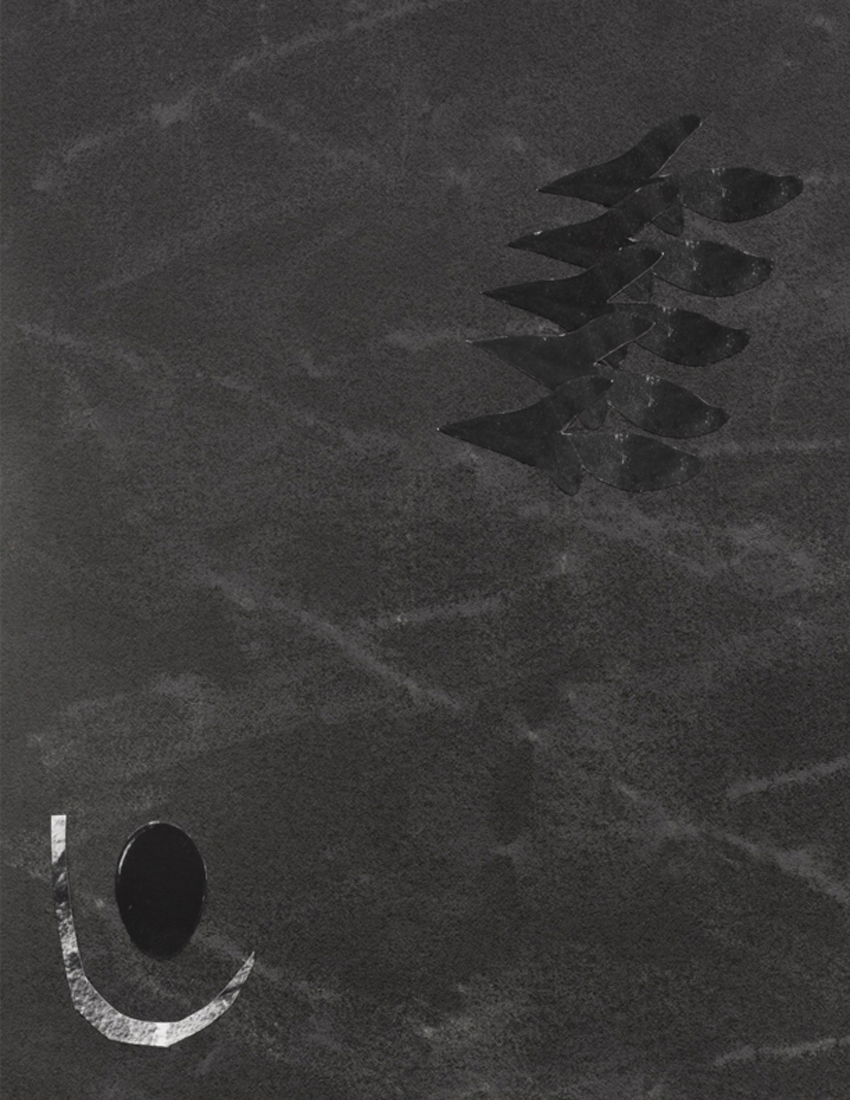

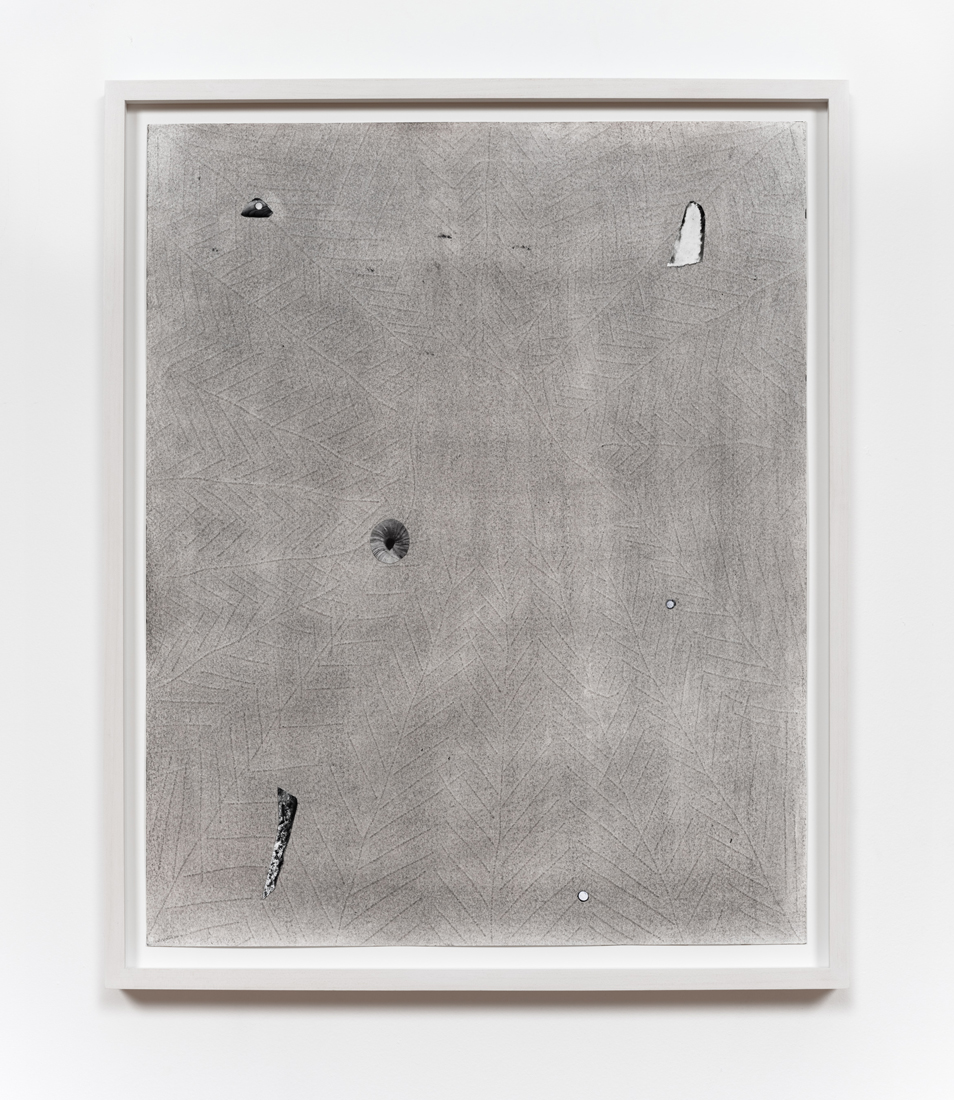

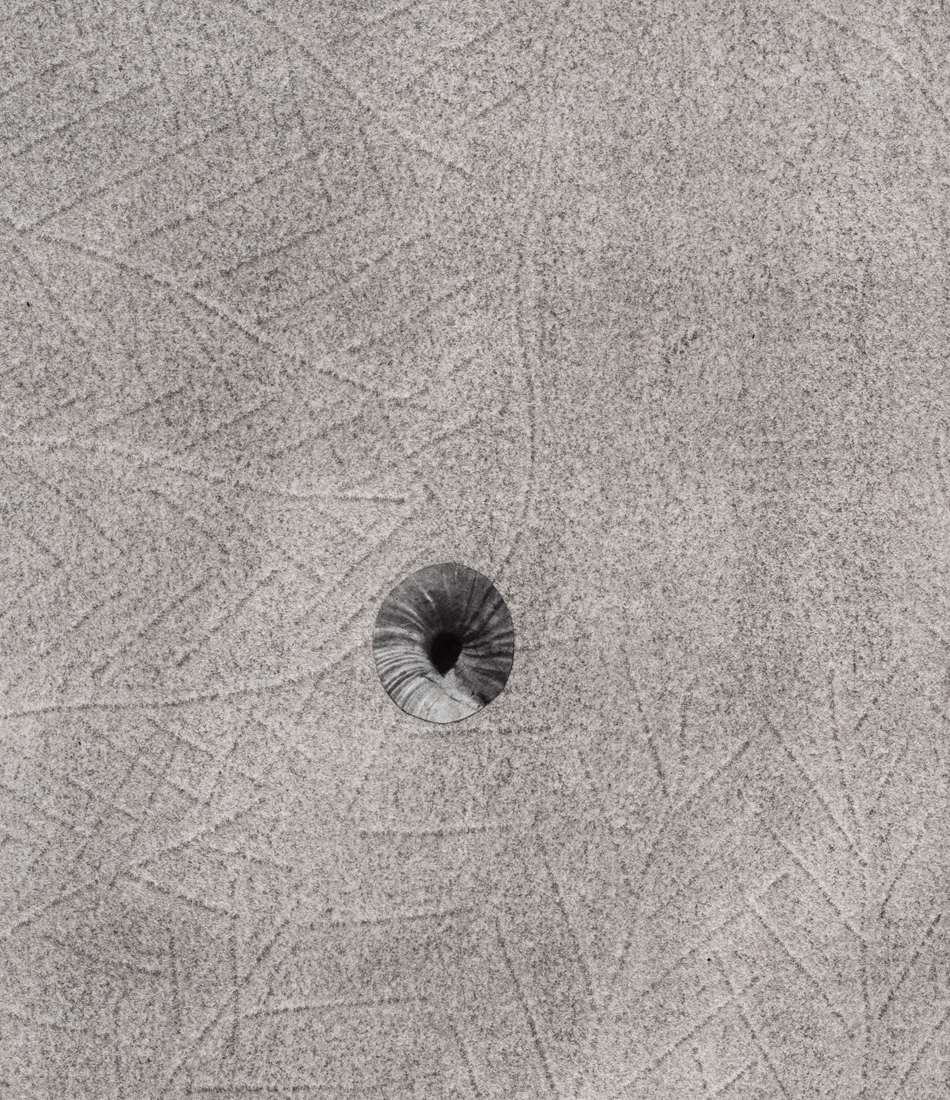

Through a range of physical gestures that include scanning and photocopying geology textbooks and field guides, cutting directly from them, applying both soft and hard pressure to the back of the paper to create lines in relief on its surface, gluing, bending, drawing, and erasing, Lee makes images that should be understood as single landscape photographs. But instead of representing actual, cartographically authorized places, these landscapes are meditations on the fleeting meaning of the land itself. They reach toward the aesthetics of fossils but do not mimic them. They call to mind topographic unevenness and marks upon the ground but do not add up to a functioning map. They strictly eschew horizon lines, further destabilizing traditional landscape photographic convention as well as our sense of scale. They are at once about the deep past, the tools humans use to touch and penetrate and measure the earth, and a possible deep future in which our own bodies have mineralized and become fossils themselves. You cannot extract positive identifications of the excerpted found photographs in these collages, nor can you itemize a definitive iconography. The logic of Enlightenment science and its aspirations to certainty are withheld. Instead, these photographs invite the viewer to find their balance amid spatial and temporal disorientation.

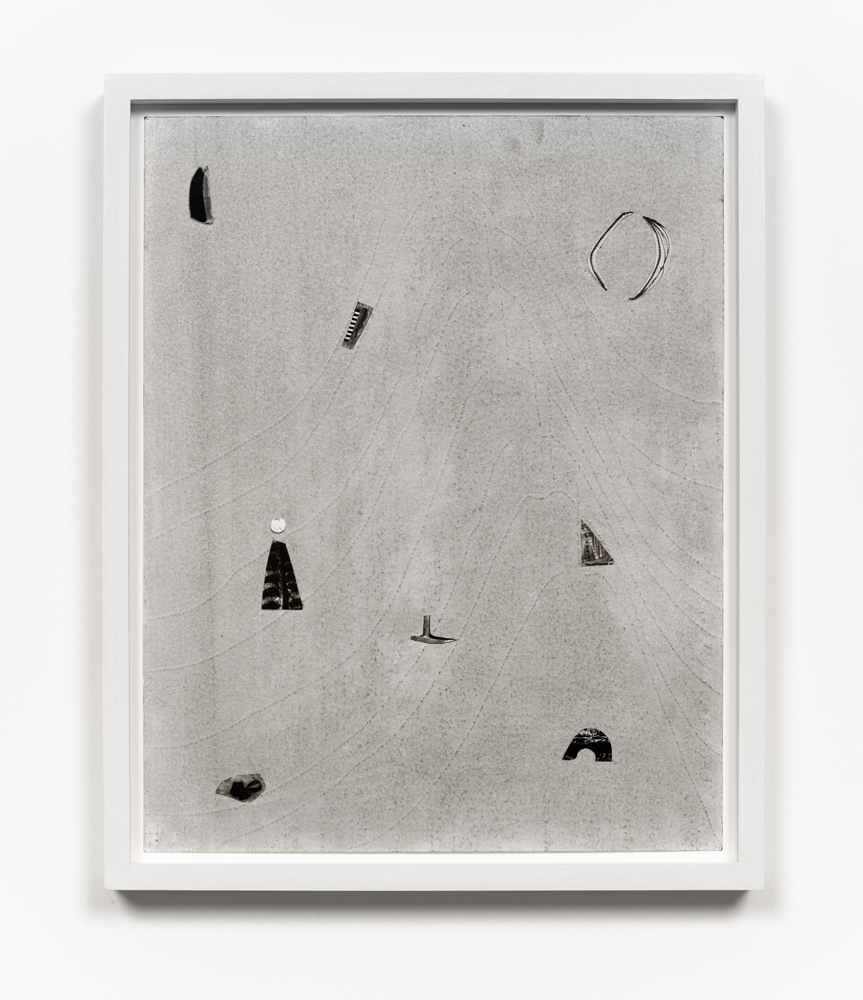

Sarah Rodriguez’s sculptures are studies in an imagined, horizontal evolutionary process. In this alternative ecology, beings connect with each other and change in ways that do not produce “higher” forms of life but rather move into the future having sloughed off the baggage of hierarchy and purity so embedded in traditional evolutionary theory. These works are made of aluminum which, in the second half of the twentieth century, became known as a quintessential industrial metal. This was thanks in large part to the unprecedented expansion of aluminum plants for military applications during the world wars. Its rustproofness, lightness, and durability lent aluminum its high modernist connotations, but this obscures its more primordial meaning. Unlike steel, the ubiquitous metal of capitalism, or bronze, the classic alloy of art history, aluminum is elemental, an unreducible, fundamental substrate of the known universe. In this way it is closer to stone than it is to high-technological fabrications. It is one of the most common elements in existence though it has no known biological function. This is particularly interesting because the baseline materials from which Rodriguez casts her sculptures are all organic forms. Rodriguez is a meticulous and ethical collector, selecting seedpods, shells, bones, and other plant and animal remains for their texture, weight, and line quality. These materials come from the disparate landscapes of Hawai’i and New Mexico, brought together under the auspices of their aesthetic qualities rather than political or ecological boundaries. The sculptures that result have a reliquary quality; the original biological matter has been completely burned away in the casting process, but their forms continue to exist in an altered state.

Fossils are often seen as the purview of grade school field trips to natural history museums and a hobby of “rockhounds,” but these lighthearted connotations obscure the profound and unsettling philosophical meaning of remnants from the deep past. Fossils are excerpts of bodies, but only in a fragmentary way; only the body parts susceptible to geologic recasting remain. In many cases, too, the fossil record memorializes beings whose kin have since vanished from existence; they are the ultimate memento mori. They are indications of life, but not life itself. In semiotic parlance, they are indexical, proof of a once animated being that has been inscribed, only partially, into rock. They record way; only the body parts susceptible to geologic recasting remain. In many cases, too, the fossil record memorializes beings whose kin have since vanished from existence; they are the ultimate memento mori. They are indications of life, but not life itself. In semiotic parlance, they are indexical, proof of a once animated being that has been inscribed, only partially, into rock. They record the deeply intimate relationships between the biotic and abiotic, the ephemeral and the near eternal, between movement and stasis.

The works in this exhibition share a fossil-like alchemy. The creatures represented in these collages and castings were once in motion but have now come to a standstill. These pieces are testaments to the range of movements living things possess, but they also record the movements of the artists’ own muscles in their acts of creation. The result is less a freezeframe of arrested motion than it is a study in diachrony, multiple timescales operating simultaneously in an echo of natural processes. In Lee’s Fault Condition 5, for instance, we see found, decontextualized fragments of geological artifacts arranged on darkened paper that her hands have bent so many times the photographic emulsion has fallen off along the creases. Lee’s photographs push the medium beyond its physical limits to find resonance with the land itself and the ways it has been inhabited, transformed, and defaced over eons. The unified form of Rodriguez’s Flow, swarm, follow, sprint obliterates traditional biological taxonomy. The exact species of the plants and animals from which these fragments were cast are intentionally obscured by machined cuts. Teeth sockets, the striations of wood, the veins of a leaf, and interrupted lengths of bone are unified by welded joints. And something else entirely emerges that is lightweight and monochrome and wild and that embodies an incomprehensible sentience.

I read these works as impartially prophetic. The more one contemplates, as these artists have, the ancient past, the interconnectedness of biological tissue and inorganic materials, and the complicity of art history in the dominant creed of western science, the more possible it becomes to imagine an unfathomably distant future and the creative practices to explore it. Rote classificatory schemes start to seem arbitrary. Hubris gives way to humility. Ground truth feels ever more elusive. And the unknown brings with it an openness, a fearlessness, and the deepest form of curiosity.

– C. J. Alvarez