Downs & Ross is pleased to present The Making of Reflections in a Golden Eye, Jacqueline Fraser's first solo exhibition with the gallery. Continuing her film-inspired series of "The Making of..." exhibitions, this body of work was made while watching the 1967 film by John Huston of the same name. Rather than outline the film's plot, this collection of collages and assemblages chart the feeling of the film, translated through contemporary cultural clippings that convey a general anxiety and thrill of what it means to be alive today. Starring Elizabeth Taylor and Marlon Brando, the film tells the story of a murder at a southern US army base in the late 1940s. It recounts repressed and unrealized desire, lust lost in translation, and insecurity about connecting, or an inability to bond, with those closest to us. A master at alluding temporal or territorial specificity, Fraser takes elements of popular culture from a diversity of eras and remixes their symbols to offer a historical lineage of today, lading each with camp and the framework of cinematic technique.

The exhibition's structure references both the pre-and post-production processes of filmmaking—from the mood board and pin-up to the cutting in the editing process. Extending the immersive theatricality of her other "Making of" projects, which most recently include “The Making of Maria by Callas" (2020), "The Making of Beatriz at Dinner" (2019), and "The Making of Dressed To Kill" (2019), Fraser constructs a stage upon which viewers can project, complete with pink tinsel, a material only-seemingly luxe. Using a black ribbon to grid-out the walls, she frames the assemblages installed along them. She employs the same ribbon to hang the sculptures in the center of the gallery as a mode of freeze-framing. This installation strategy is a continuation of the large-scale installations of the late 1970s for which she gained international recognition. Elements such as wire figures and bold fabrics or textiles have persisted as defining features of her work.

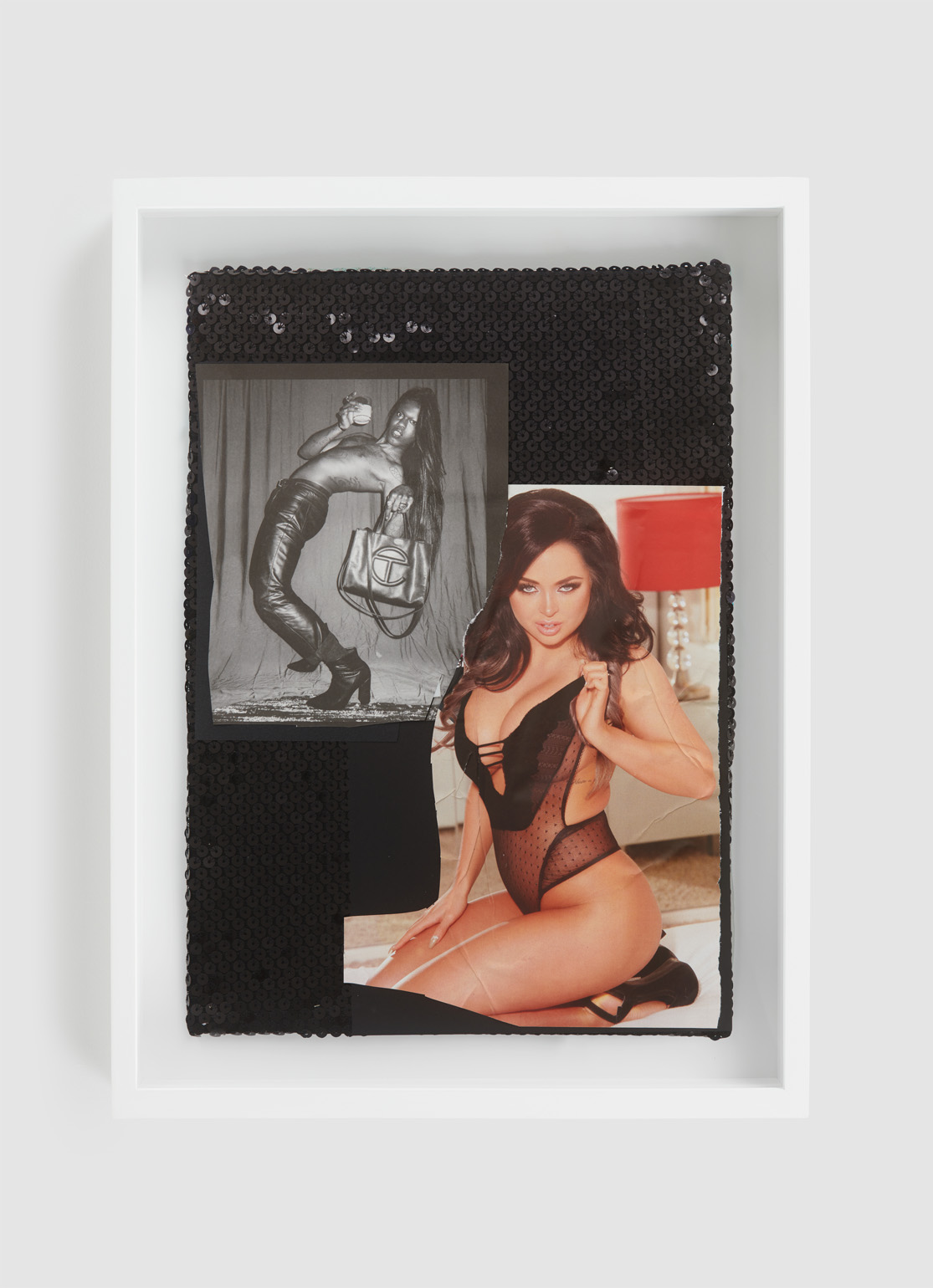

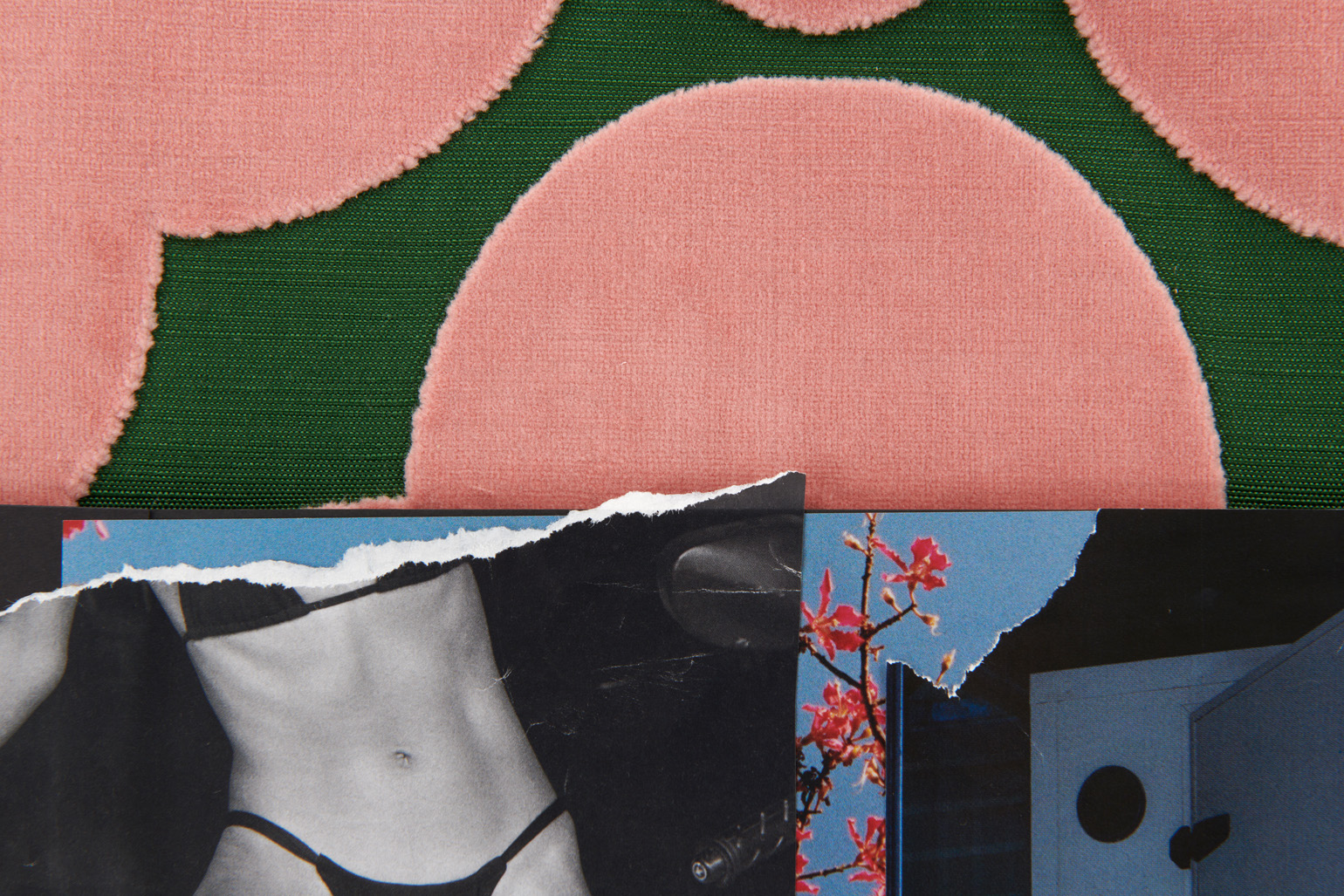

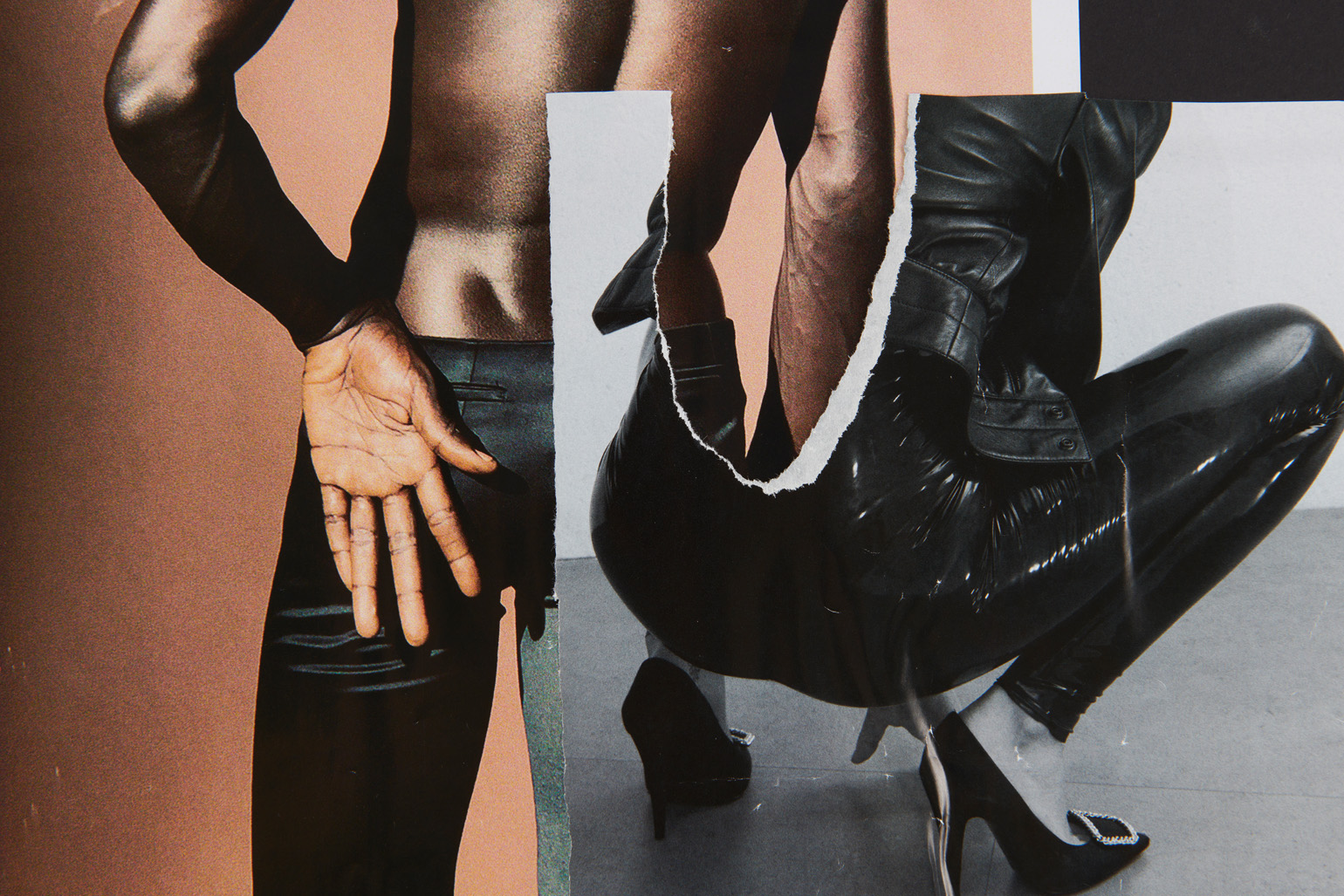

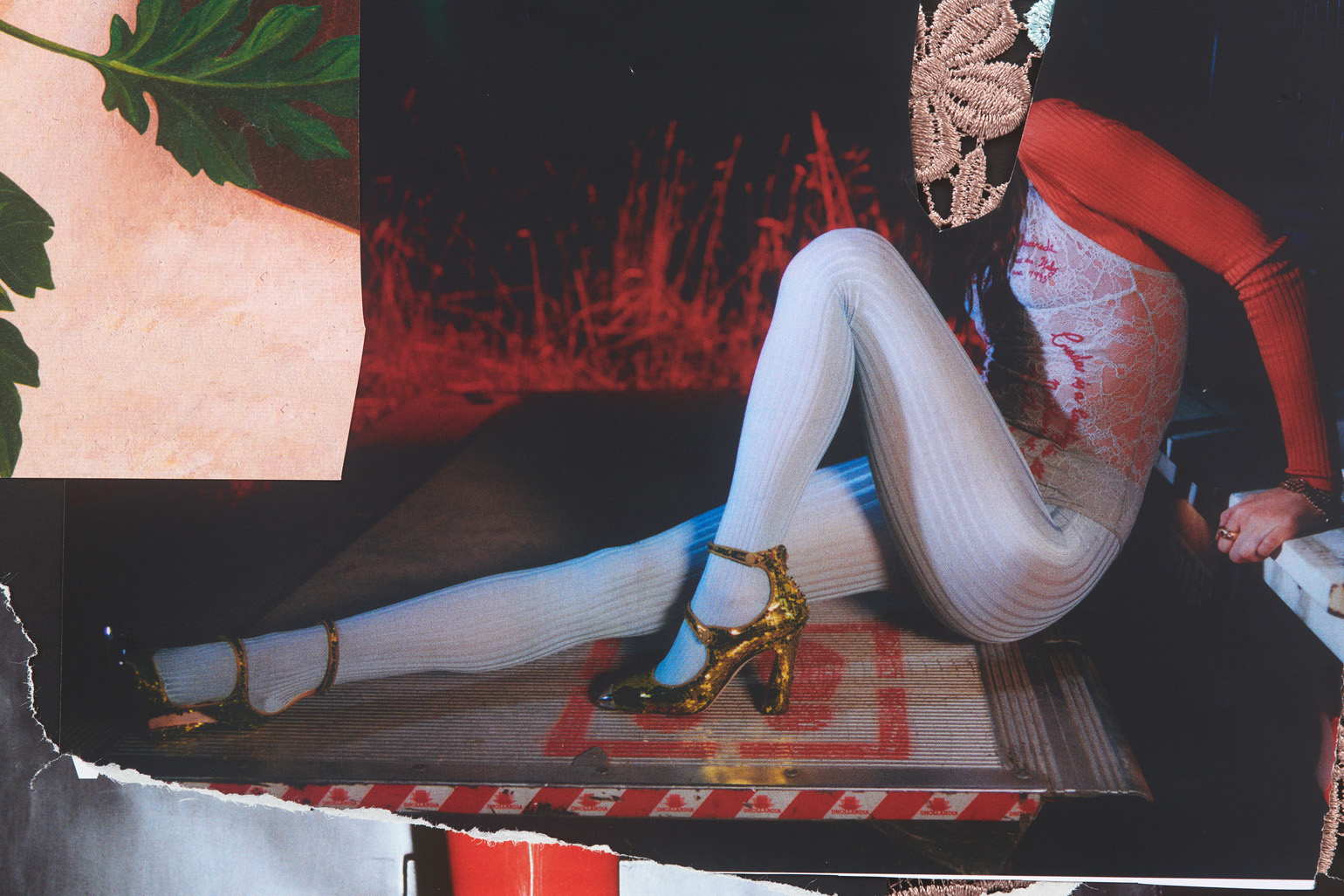

Here, the assemblages are composed of fast-fashion items and found images—a mash-up of news clippings, images of pin-up girls, and advertisements—Telfar and maybe Gucci—screen grabs of paintings of flowers, and women. These sculptures are outfits devoid of a body or mannequin, a space for a character to fill. The photos are also without faces, stalling any easy character translation. In one, a green tulle dress is adorned with cut-out photographs—a black man's bare back with tight trousers, bejeweled hands, and a leg. On the ground are a pair of heels with hair cascading out of them—an art historically-charged object of fetishization and desire. Together these images tap into wider notions fetishization—of women, of black bodies, of indigenous bodies, and youth, especially in contemporary society and instigated by the culture industries. Throughout her career, Fraser has sought to defy a definitive reading, often bridging several narratives. Many of her early works addressed national histories related to her native New Zealand, but always with a multitude of references to slip out of any easy identification. While she doesn’t prioritize a time period or location over another, she does play upon the power dynamics between varying ideologies and cultural expectations.

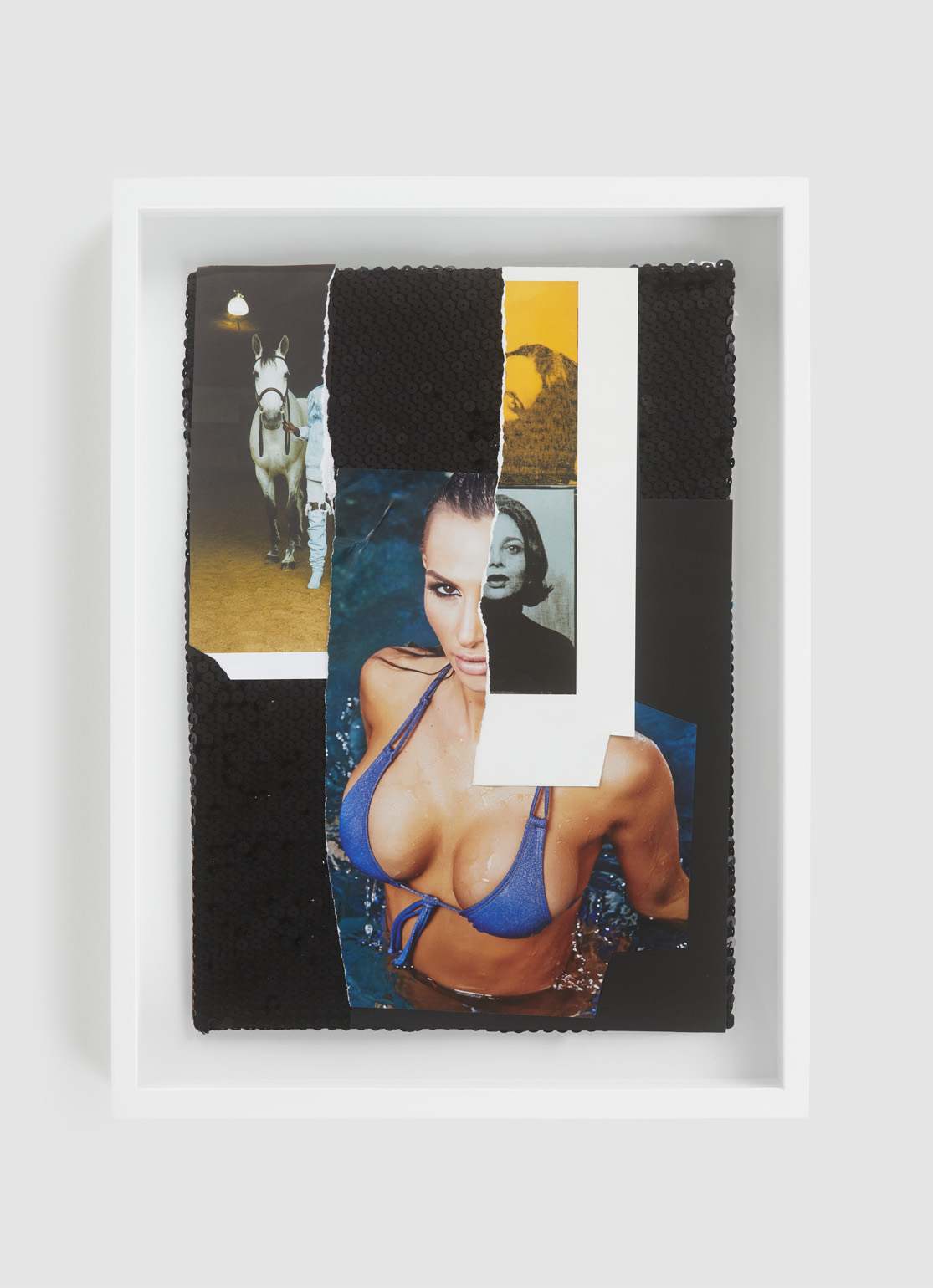

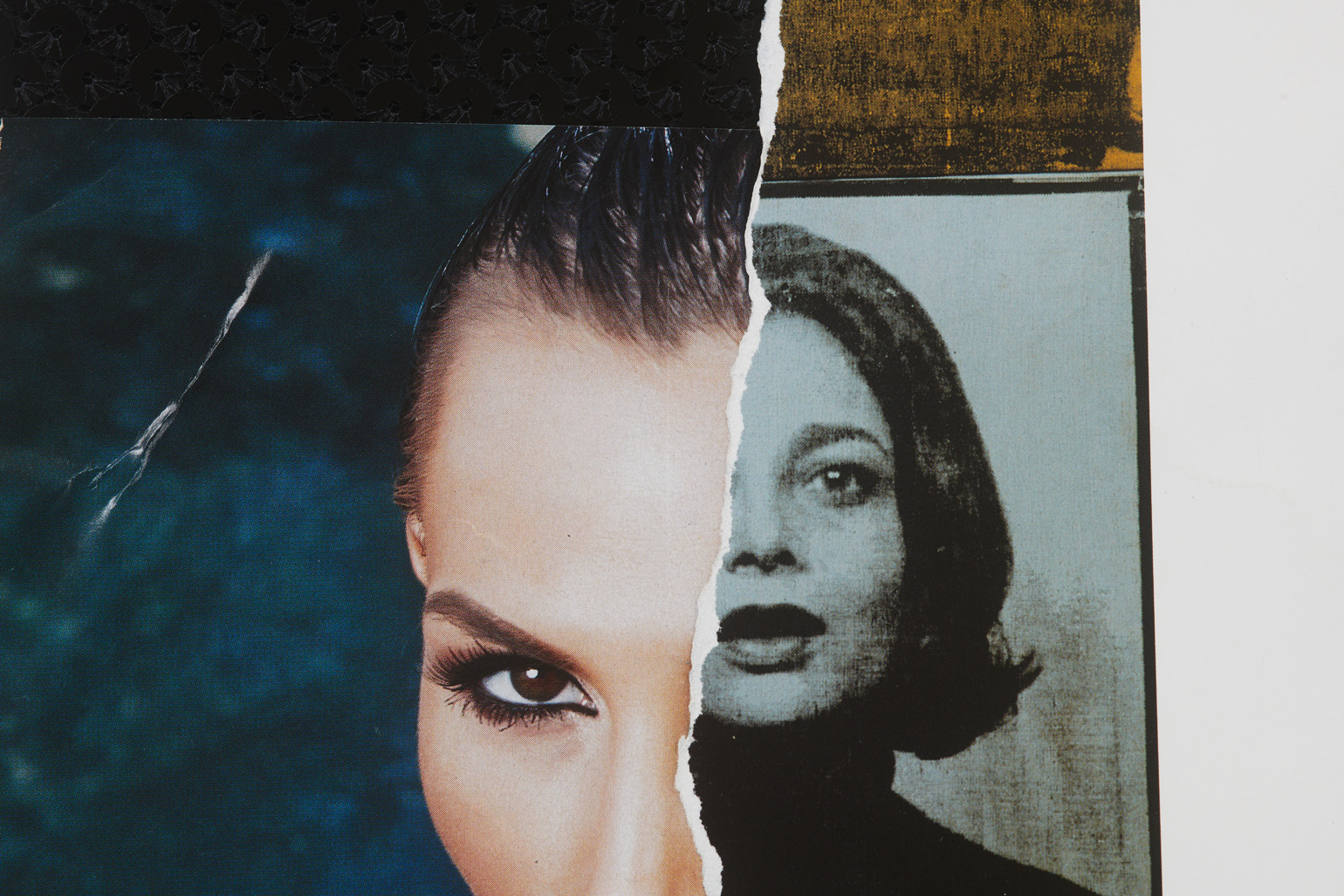

In this new suite of collages, you can practically see the girls raising their eyebrows and teasingly inviting you to join them; however, upon approach, they will keep you at arm's length. Like Elizabeth Taylor's deliciously cruel Leonora, they pull you in only to humiliate you for power and entertainment. They incorporate the same lexicon of imagery as the assemblages, while also including black sequined textile and lace doilies, interspersed with photos of Elizabeth, a bare back, and horses. This collection mixes old-school Hollywood tropes of Americana with today's "horse girl" or, rather, "horse boy." As Whitney Mallett argues in "Why Are Horse Girls Always Trending? Charting the Giddy-Up Energy from the Girl Next Door to Gucci," "horse girls are a personification of alienation." She elaborates, "whether we're changing the world, or in the meantime before it changes, just trying to cope and escape, horse girl energy is about embracing your weirdo self, unhinged and unbothered."

Marlon Brando's sultry voyeur Major Penderton embodies this energy—barely speaking yet riding around bareback. The film complicates any Lady Godiva allusions, for while it is Brando’s character who rides in the nude, it is also he who spies on Leonora, going so far as sneaking into her room while she sleeps. Unbeknownst to him, Leonora’s husband watches him ride and believes his trot is for him—a queer desire unrequited and eventually lethal. While Lady Godiva rode naked to atone for her husband’s high taxation, here it is Brando who rides naked out of unabashed freedom on the horse of the woman he desires.

— Samantha Ozer