I first met Hilarie Mais and her late husband, William Wright, when I was 17 and a student at the National Art School in Sydney. I was instantly drawn to their worldly sensibility and kindness. Lunches at their house would run late into the night and spill over into the next day, with endless accounts about their life in 1970s New York. They spoke of blackouts and bankruptcy, of many cheap or illegal loft spaces to work and live in, and of a thriving scene for artists in Manhattan. Laurie Anderson could be found playing the violin while standing on an ice block, and Judy Chicago exhibited The Dinner Party, amidst the burgeoning feminist movement. Max Hutchinson, an Australian, opened one of the first galleries on Greene Street in 1968 where he exhibited a pioneering show of drawings and paintings by Louis Bourgeois. There, Mais met Bourgeois, one of her heroes. To me, a young art student, these stories were fuel.

Mais and Wright moved to Australia in 1981, they put down roots, and Wright started a gallery in Sydney. Mais and Wright were both artists working together, while Wright doubled as a gallerist. This was the first time I encountered such a collaboration, and their dynamism influenced my decision to open my own gallery in Sydney. Whilst recently foraging in a bookshop, I found a copy of Australian Sculpture Now, a rare catalogue. To my surprise, it included a letter to the author from Mais:

My interest starts in English vernacular styles, early modernism, like Kenneth Martin. My early work was a kind of lyrical constructivism, somewhat between gesture (bodily rhythmic) and emotive form. Throughout, I have never been committed to the idea of pure form, for its own sake, and am more interested in form, or matter, for its capacity to evoke or invoke emotion…

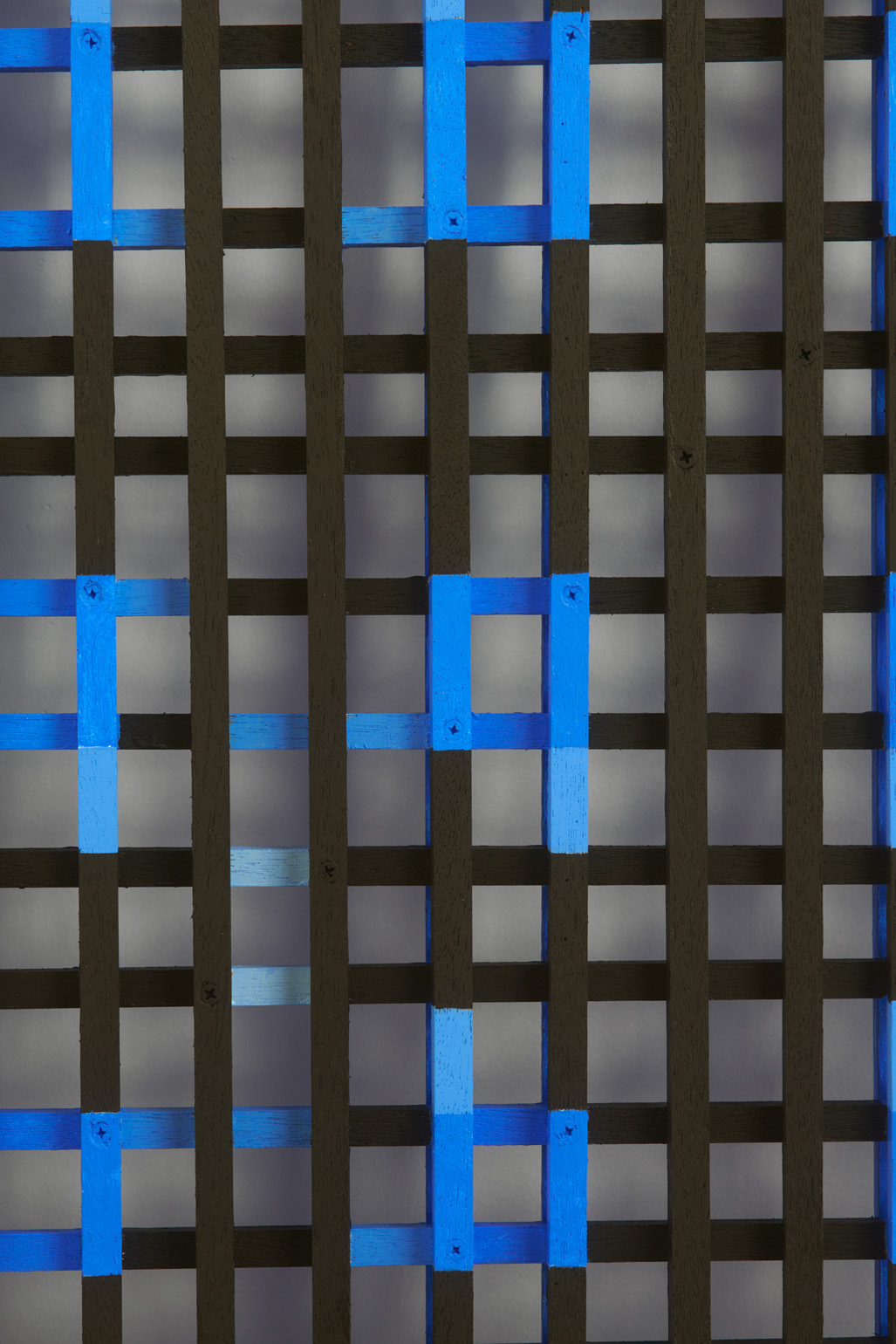

In a recent conversation I learned that Mais was taught by the British painter Euan Uglow. This meticulous painter only worked from life, using a very elaborate geometric mark-making system. Following this mentorship, Mais envisioned the possibility of using the grid as a vehicle for mapping emotional content beyond the bounds of figuration.

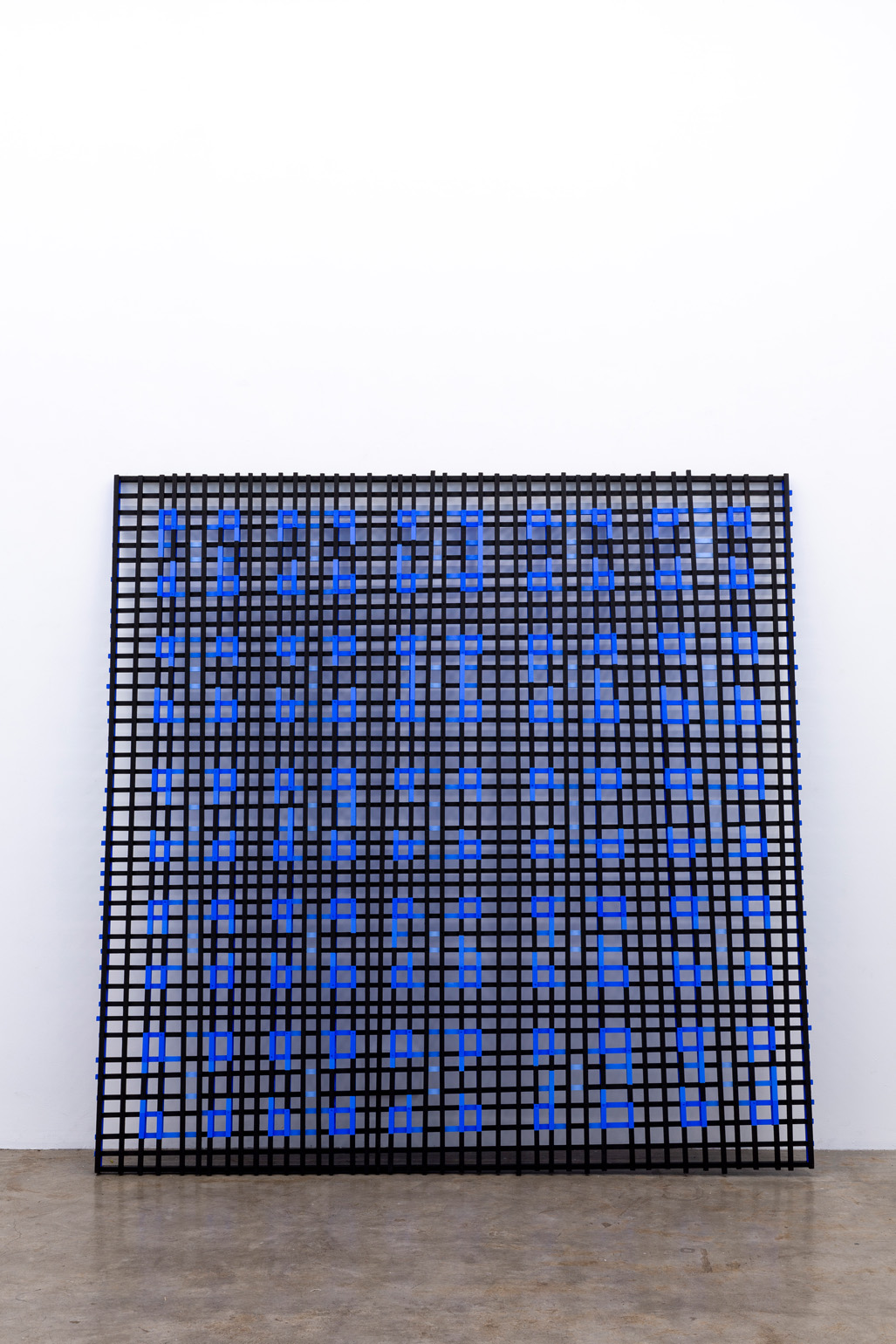

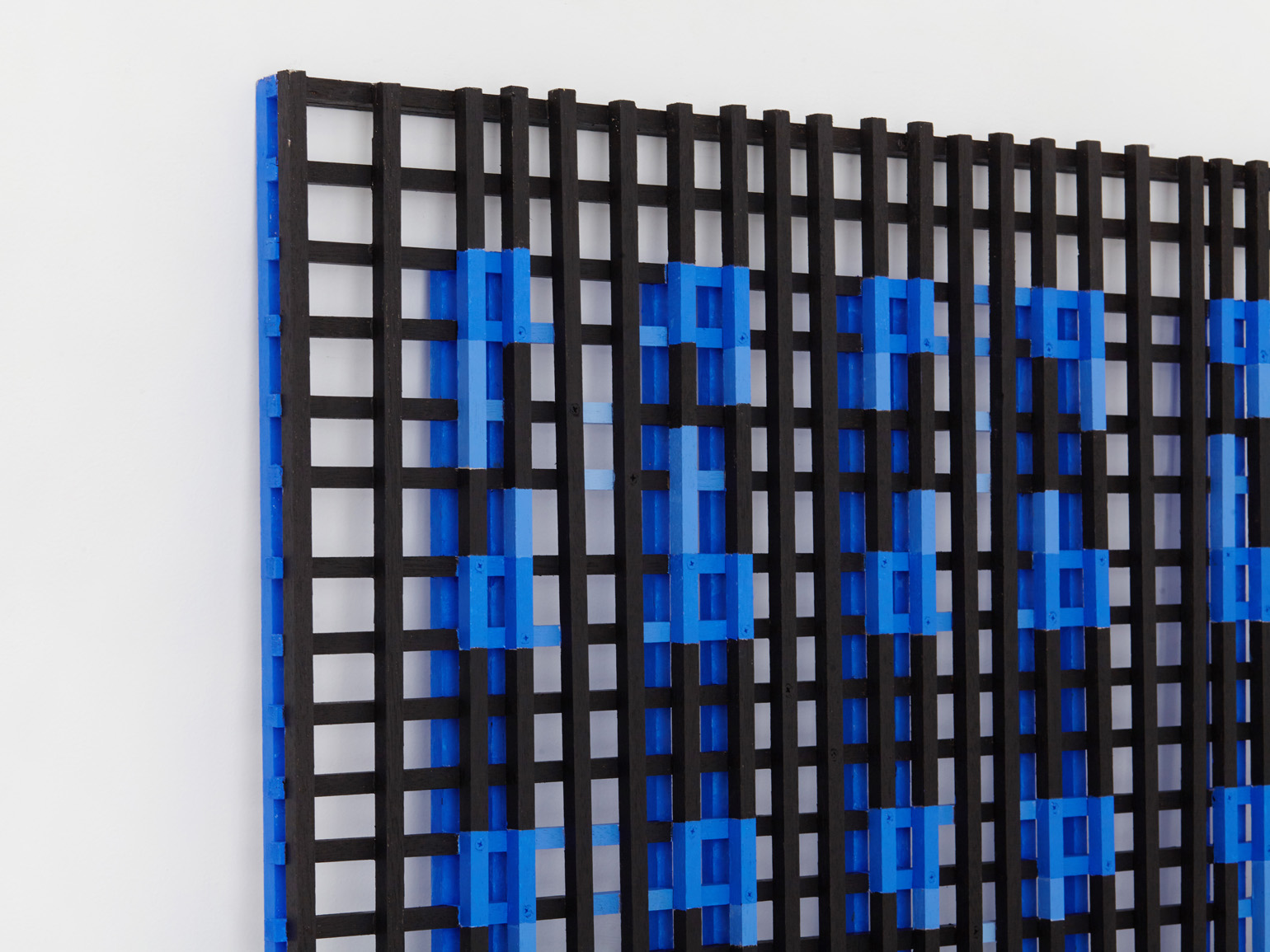

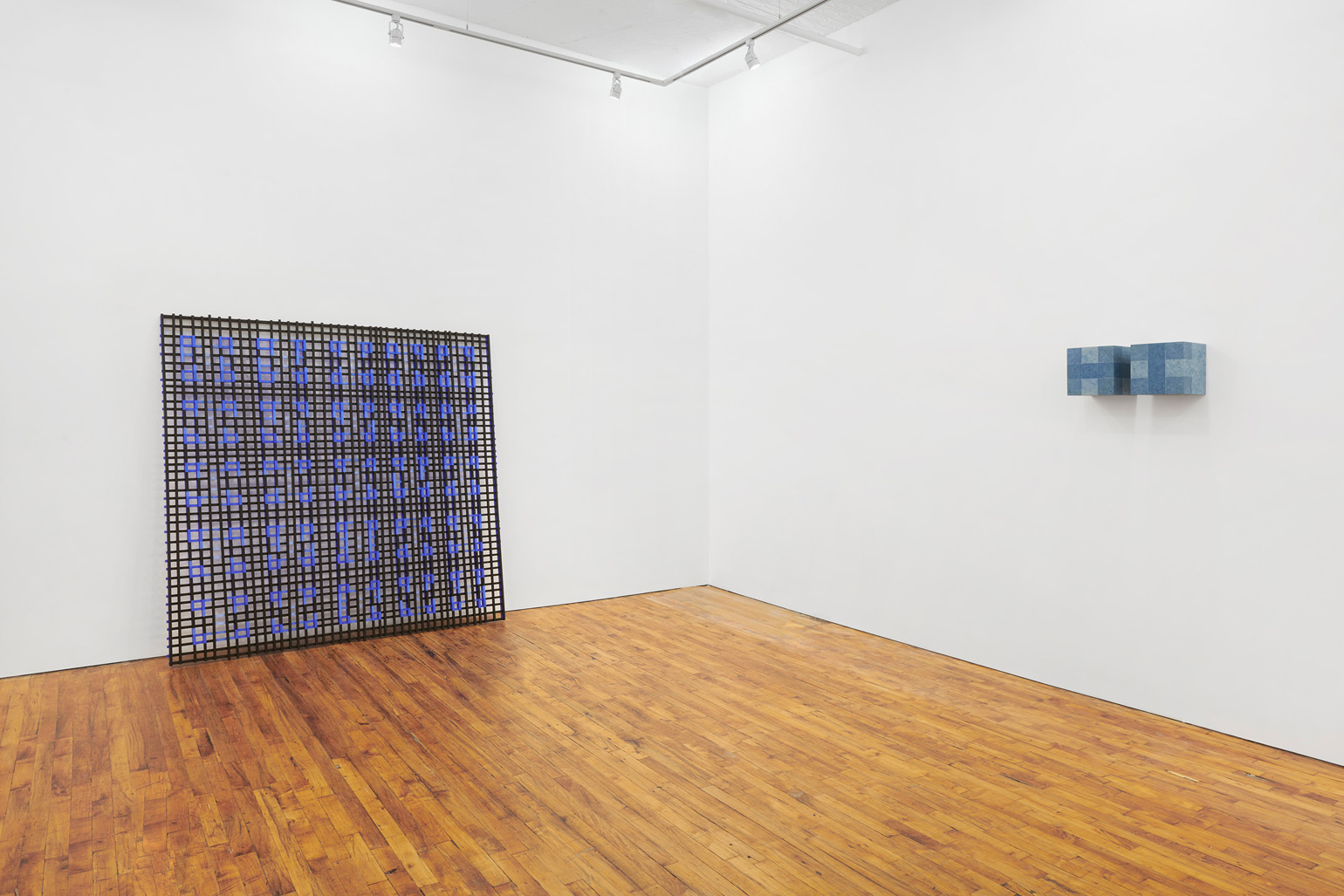

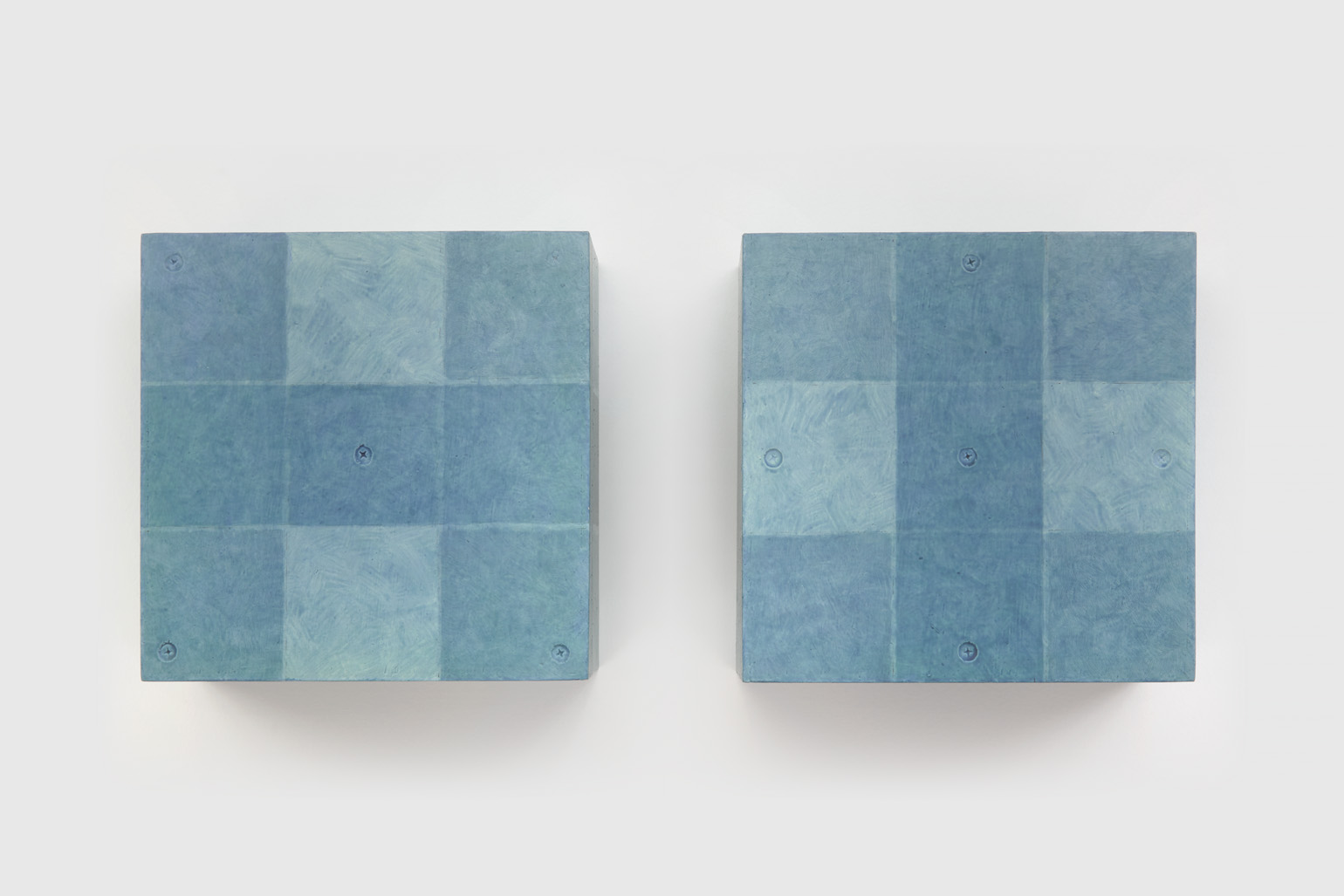

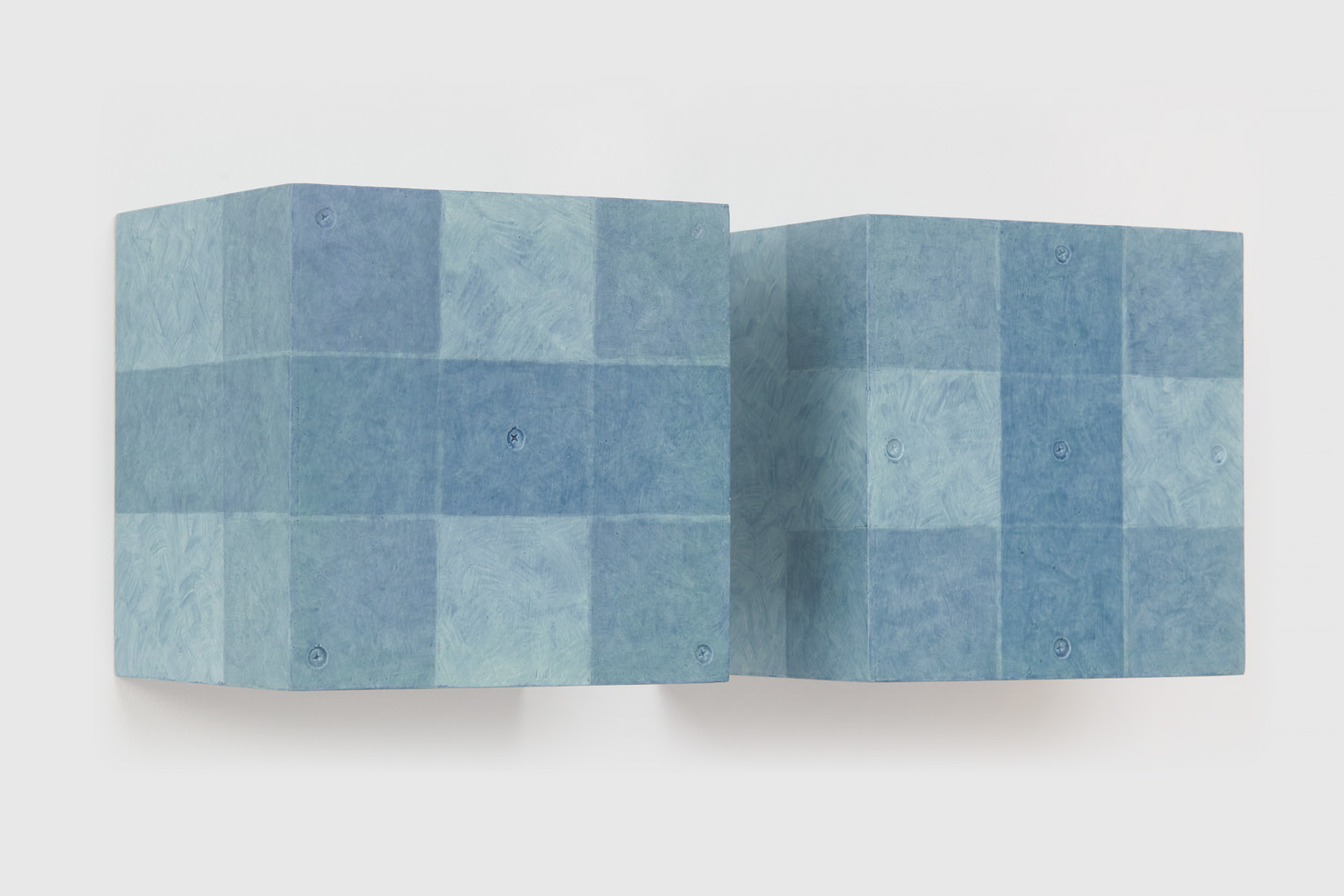

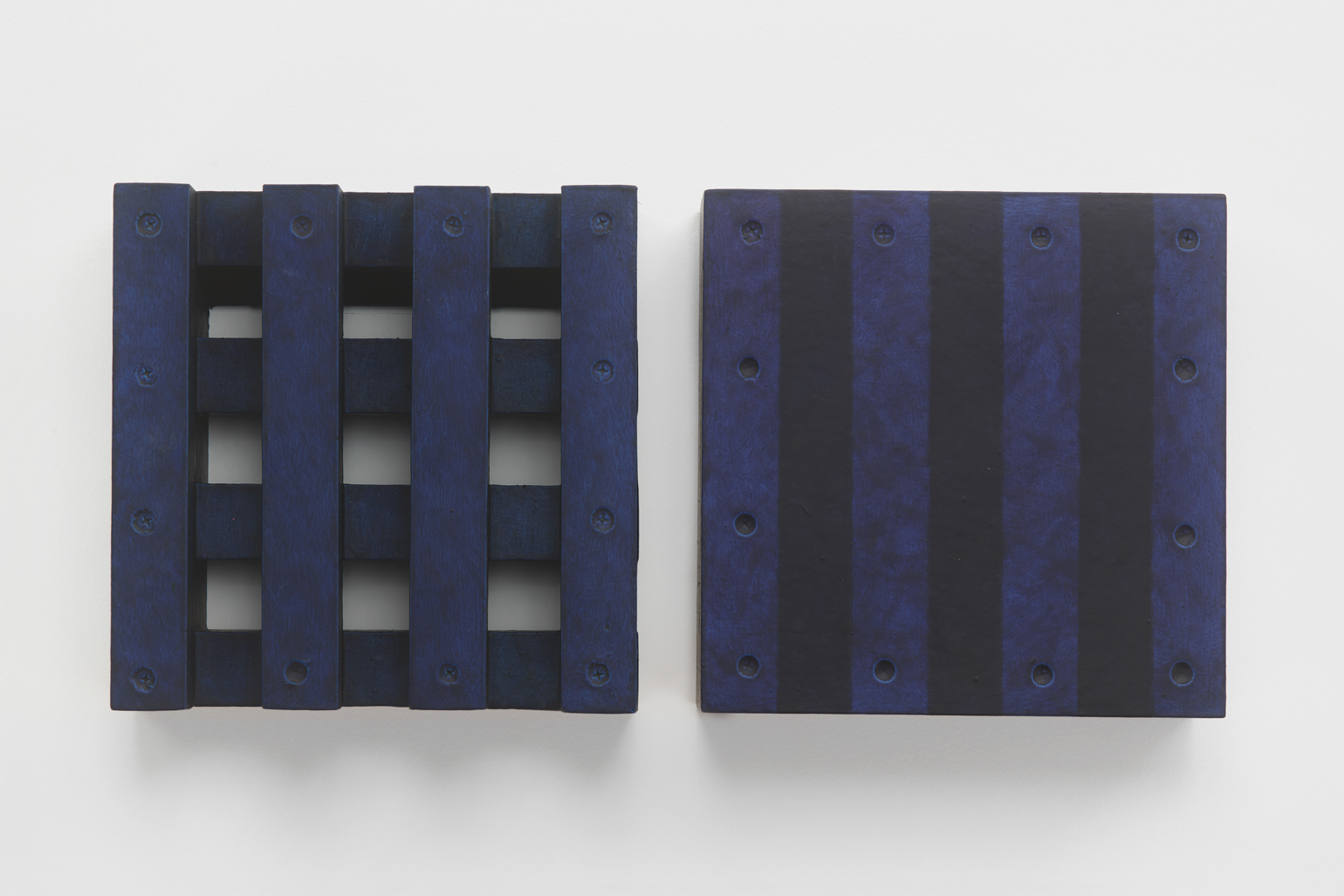

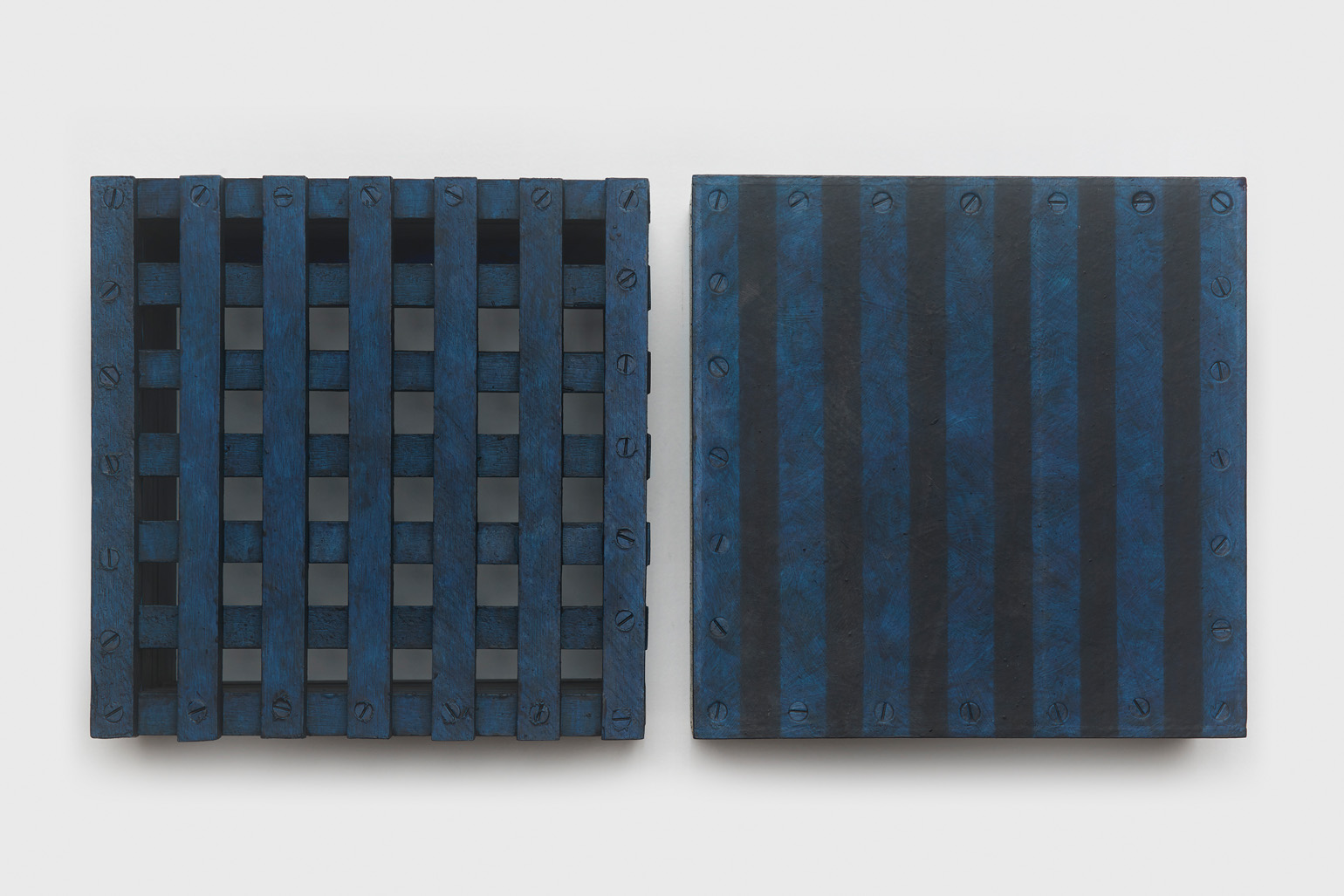

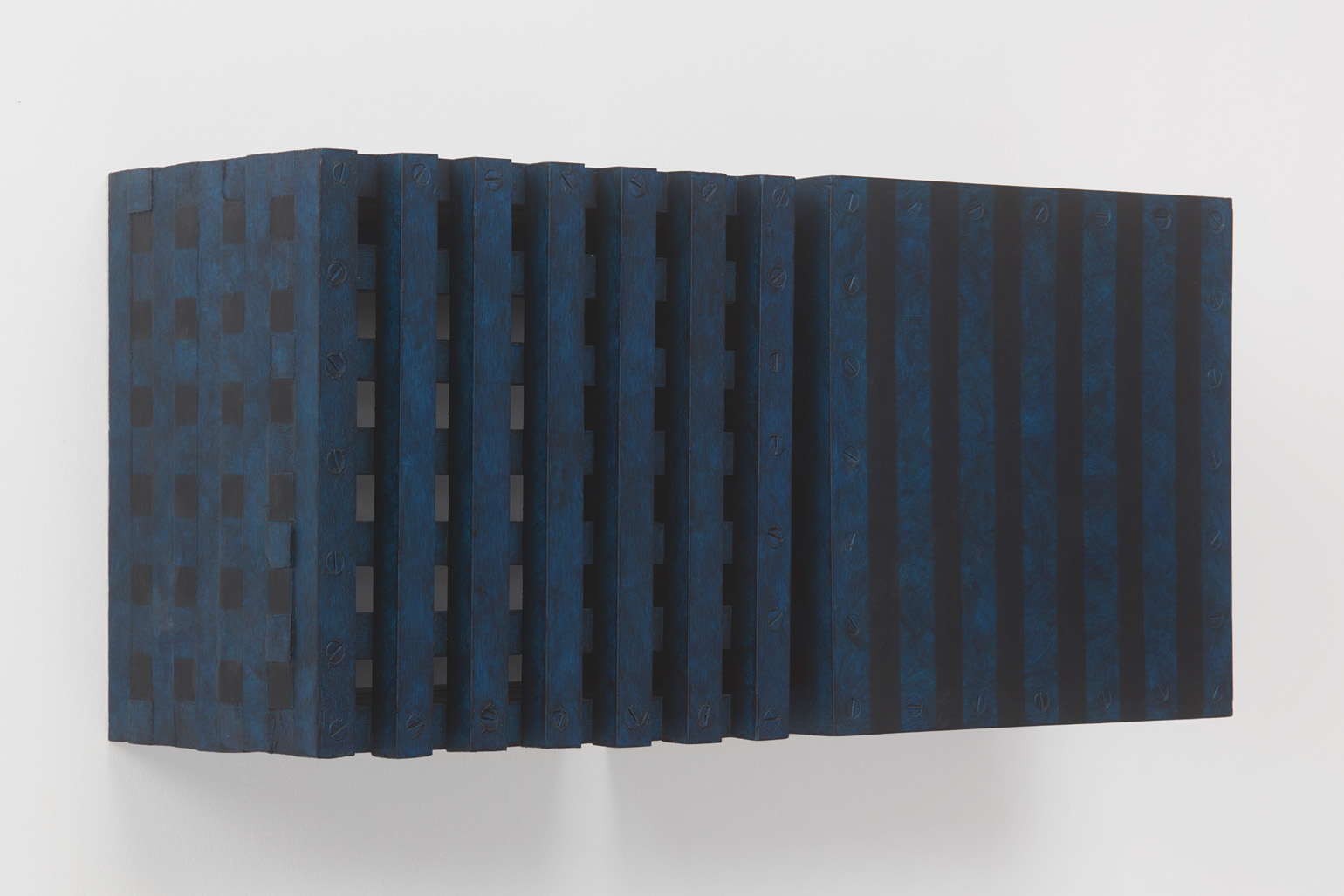

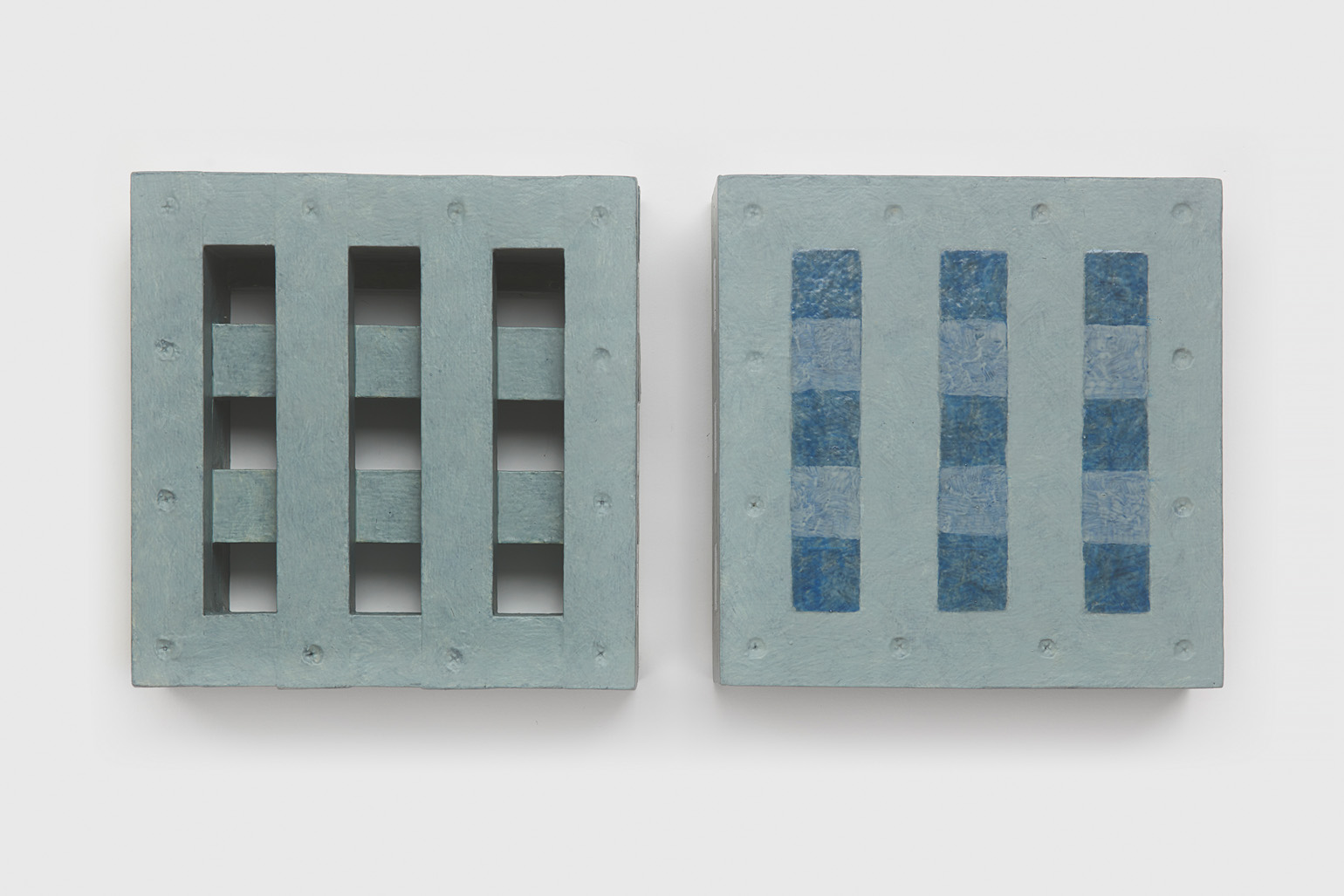

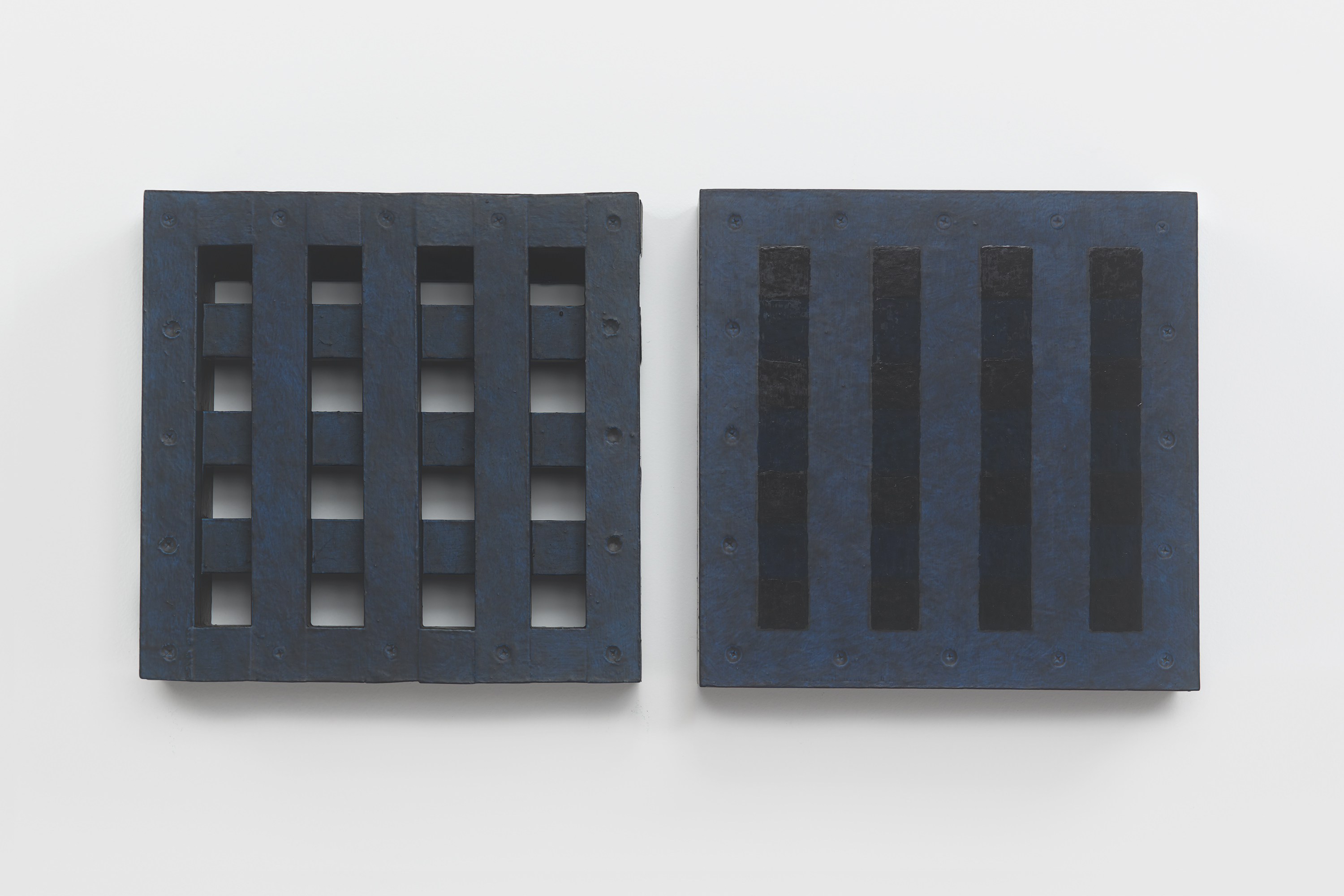

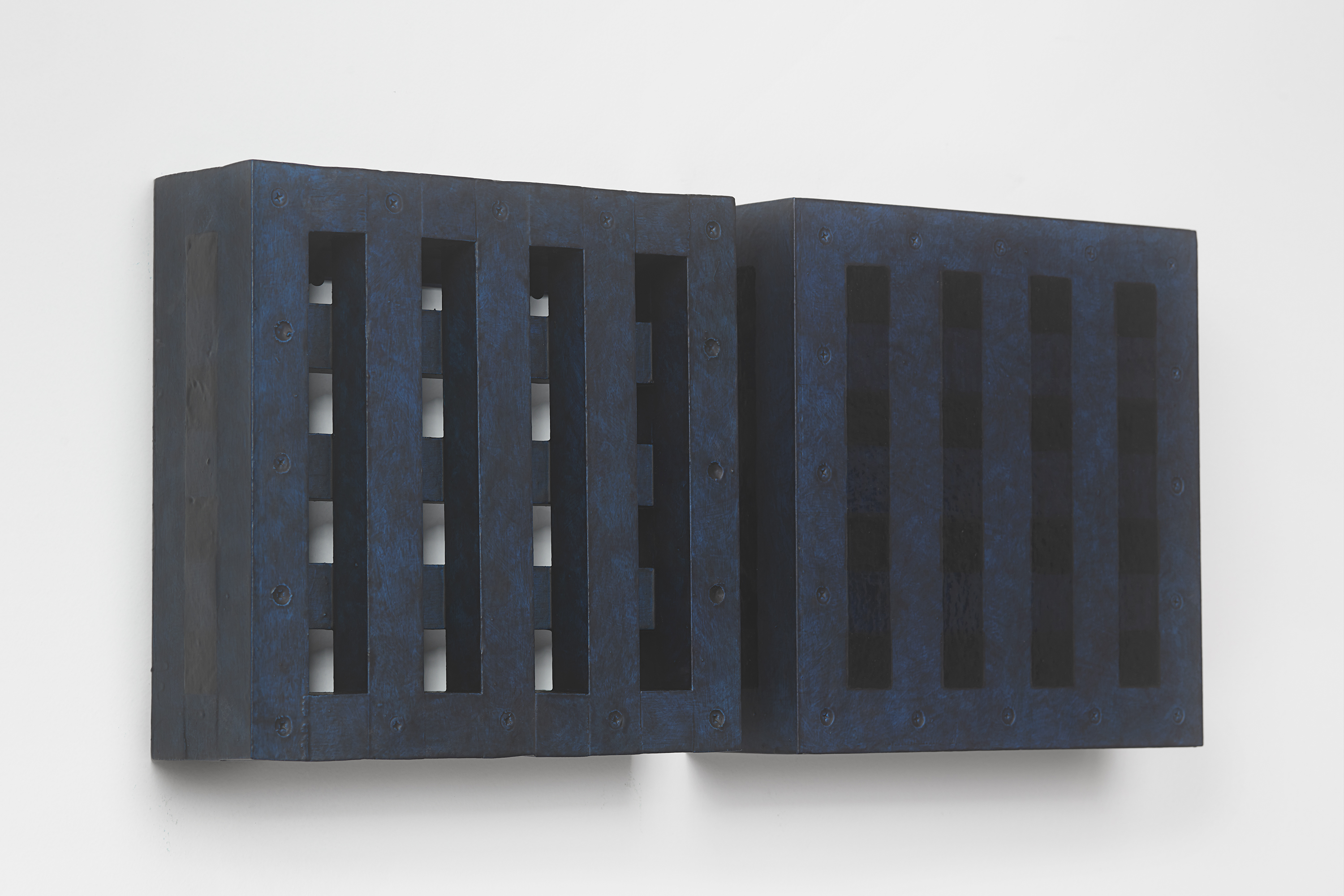

The works included in this exhibition were all made during the night-time hours: a curious connection to Uglow, who would break his self-imposed rules in the studio during the evening. Large grids are paired with small twin cubes that command presence on a smaller scale. The twin cubes hang as pairs. The left element is a constructed piece, the right is an illusion of the left existing in the slippage between sculpture and painting.

Mais finds herself revisiting the spatial relationships in her sleep and awakes to try and solve concerns within her work. She uses the memory palace technique, and it is, in essence, a nocturnal filing system. By privileging the interior mental images to drive her across the physical act of making work, she connects to Surrealism's call for the near automatic recording of visions achieved in a dream state. This is a feat that Giacometti achieved majestically in The Palace At 4 am.

In 1981, Mais showed at Cunningham Ward Gallery above Fannelli’s on Prince Street. Now, 40 years later, she returns to the city that holds incredible significance to her practice, turning full circle to arrive at this moment.