Yes, there are men in the showers drinking each other in; there are also seniors doing aqua fit, teenagers learning CPR, newborns bobbing in the kiddie pool, divers throwing themselves from unseen platforms, and sauna-going swingers staying open-minded. Like the body itself, the aquatic centre is a multicellular organism, a dripping, near-nude microcosm of the social sphere.

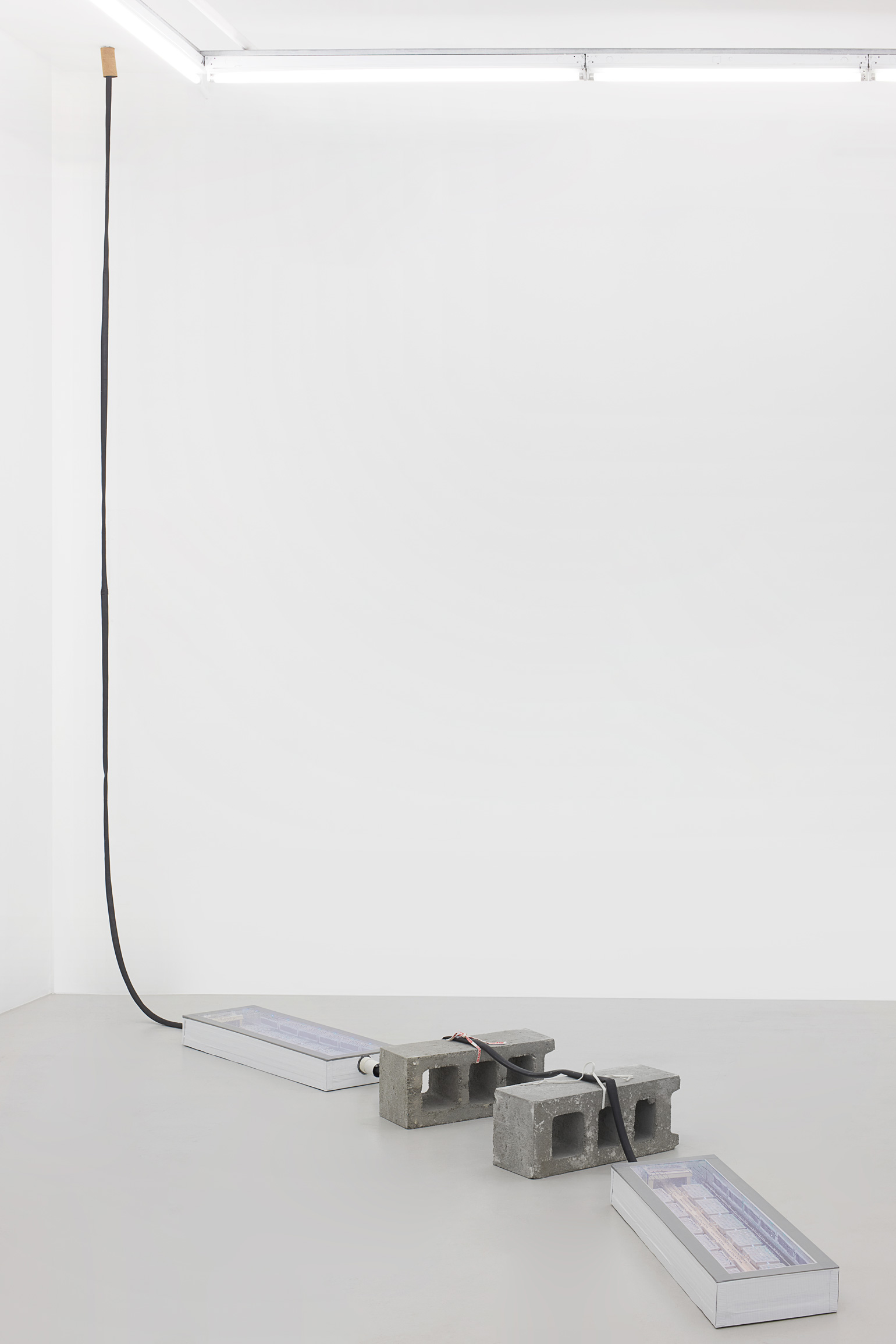

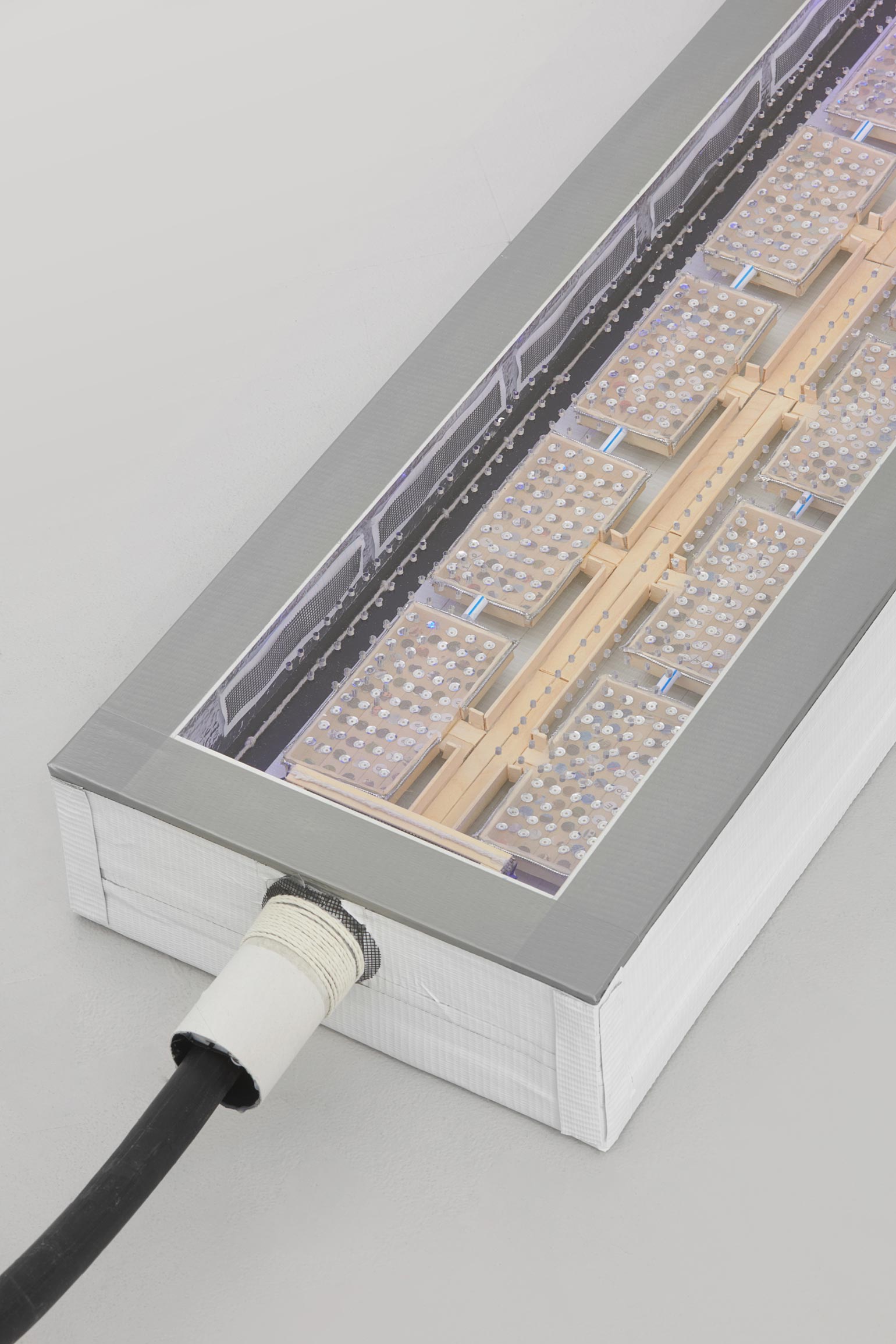

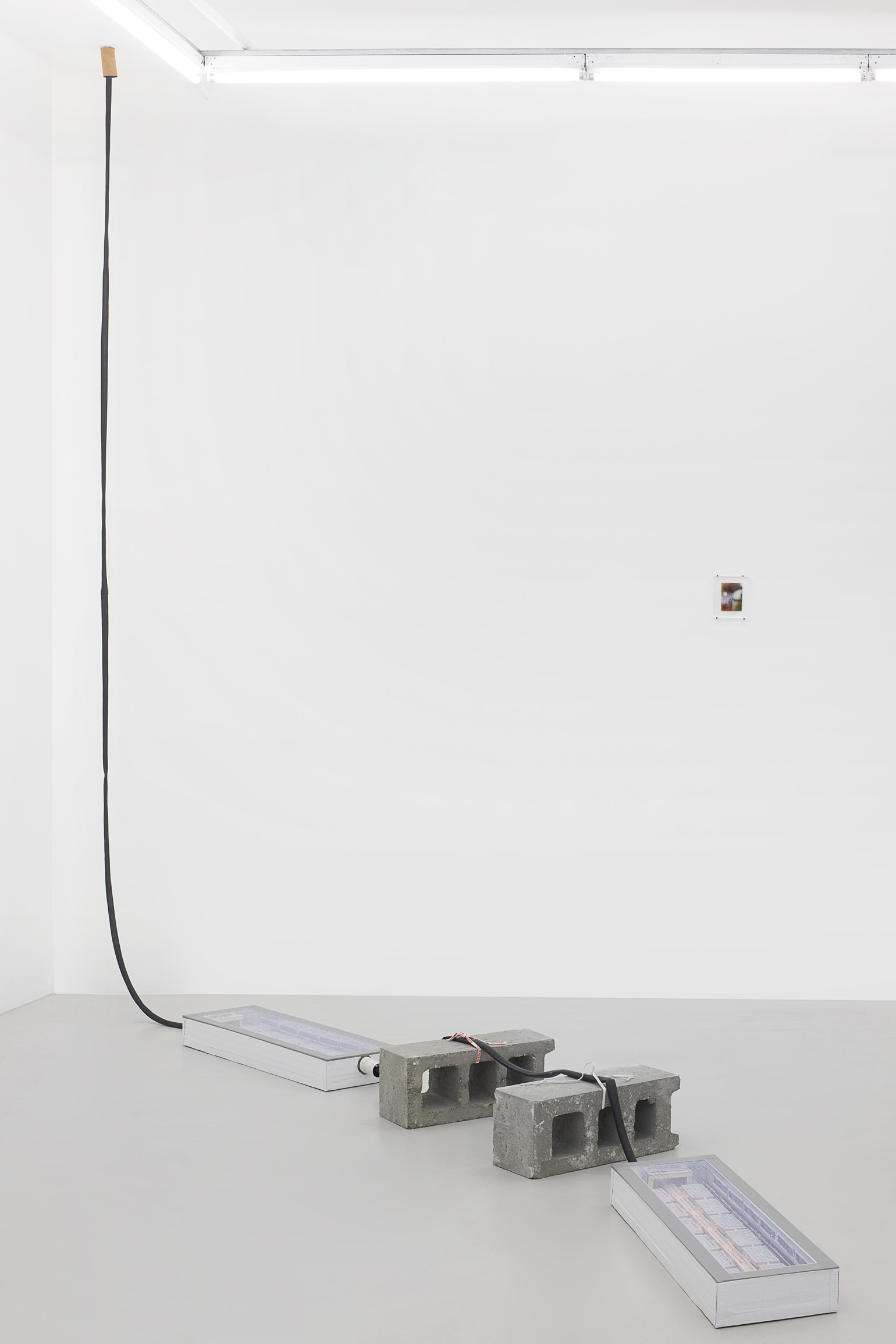

One Saturday morning, at the Vancouver Aquatic Centre on Beach Avenue, Douglas Watt spotted something unfamiliar through his goggles. There, on the floor of the deep end, were two long white boxes connected by a black tube all pinned by cinder blocks. Recognizable perhaps only to divers and pool personnel, the device—a sparger—creates a profusion of bubbles, breaking surface tension. It falsifies a softness, blurs the natural violence between water and falling body. Without the effervescence, the surface is also invisible; no matter how many times the divers looked down and plunged it, the unmodified entry remains imperceptible. This obscure machine, a lodestone for Watt, might be thought of as a guidebook or prism or blackbox for all the works in Deep End Epiphany, his first solo show in the US.

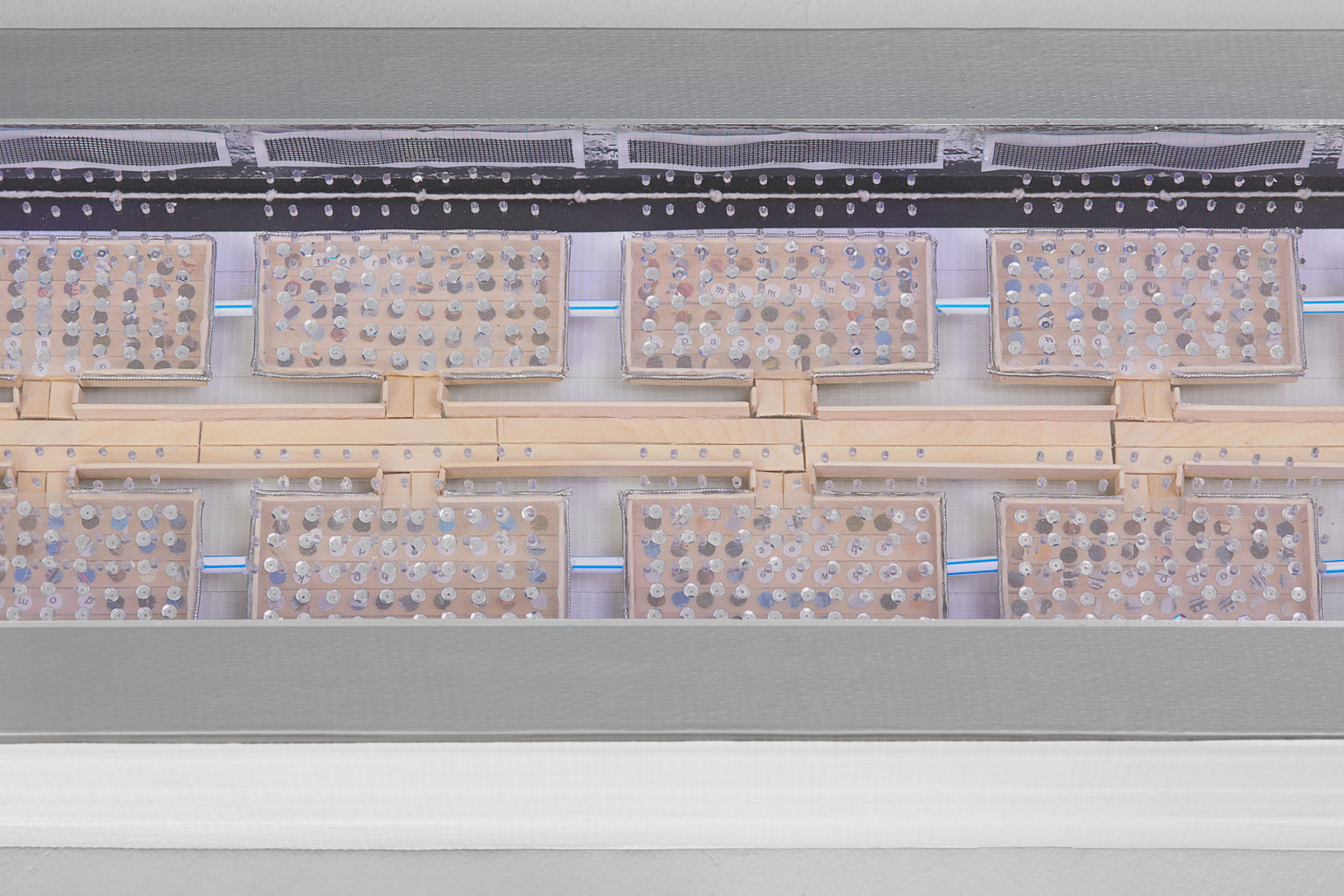

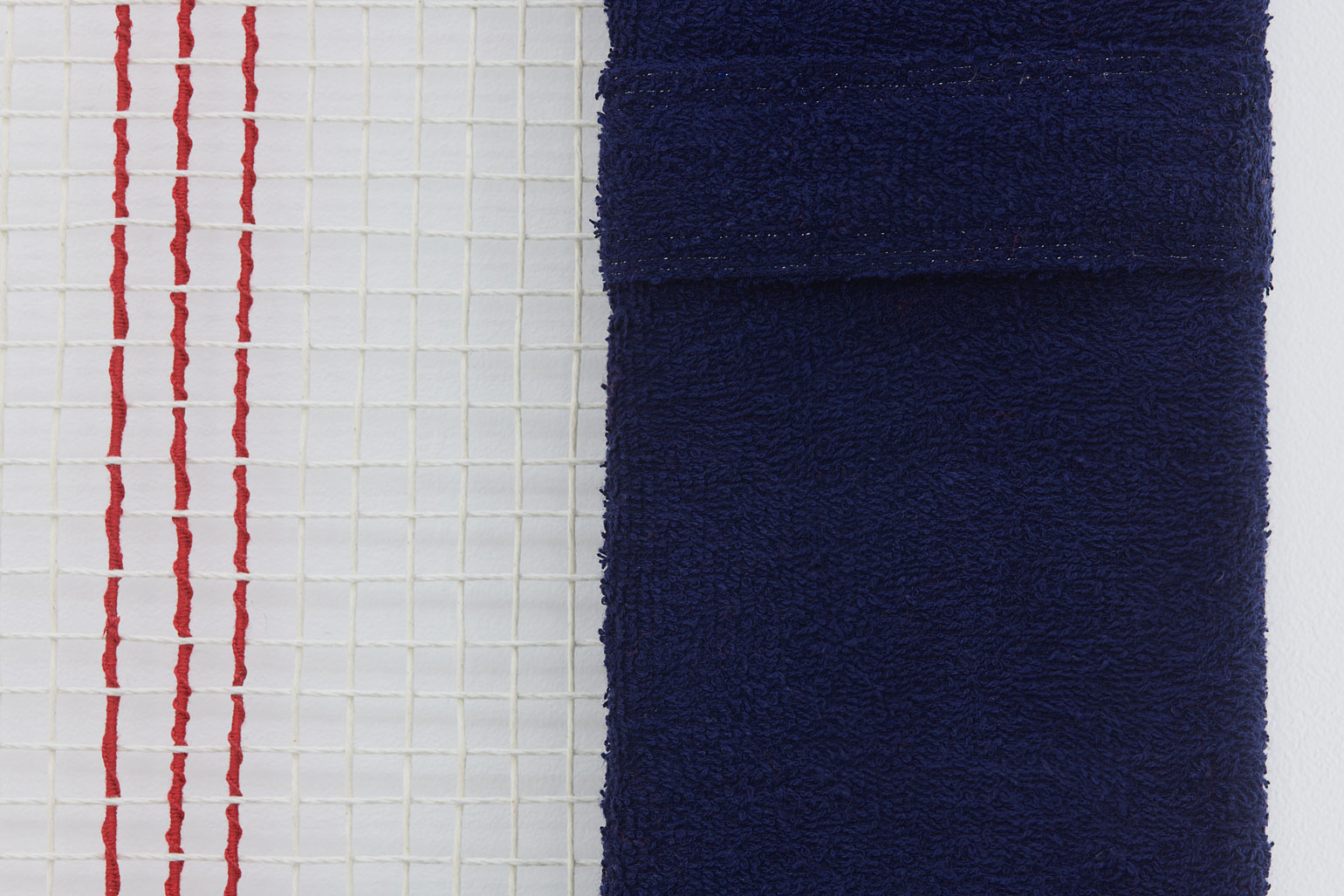

Switching from front crawl to back, Watt casts his eyes toward the sky, the sun, the rain, through the aquatic centre’s concrete skylight. Skylight Banner (2021) is an accessorized fabric facsimile of the imposing brutalist ceiling affixed dramatically to the wall with four 8” iron nails. In a libidinal flush, one might say it has the energy of a switch—on one hand, sparkly and pert, and on the other, heavy, unwavering. “Here, the sky is so strange. It’s almost solid… as if it were protecting us from what’s behind,” utters John Malkovich’s character Port, in The Sheltering Sky (1990) while fucking his wife on the precipice of a cliff in the Maghreb—an expanse the pair can’t resist tunnelling further and further into, relinquishing all safeguards. Is the sky benevolent or merciless? Protective or oppressive?

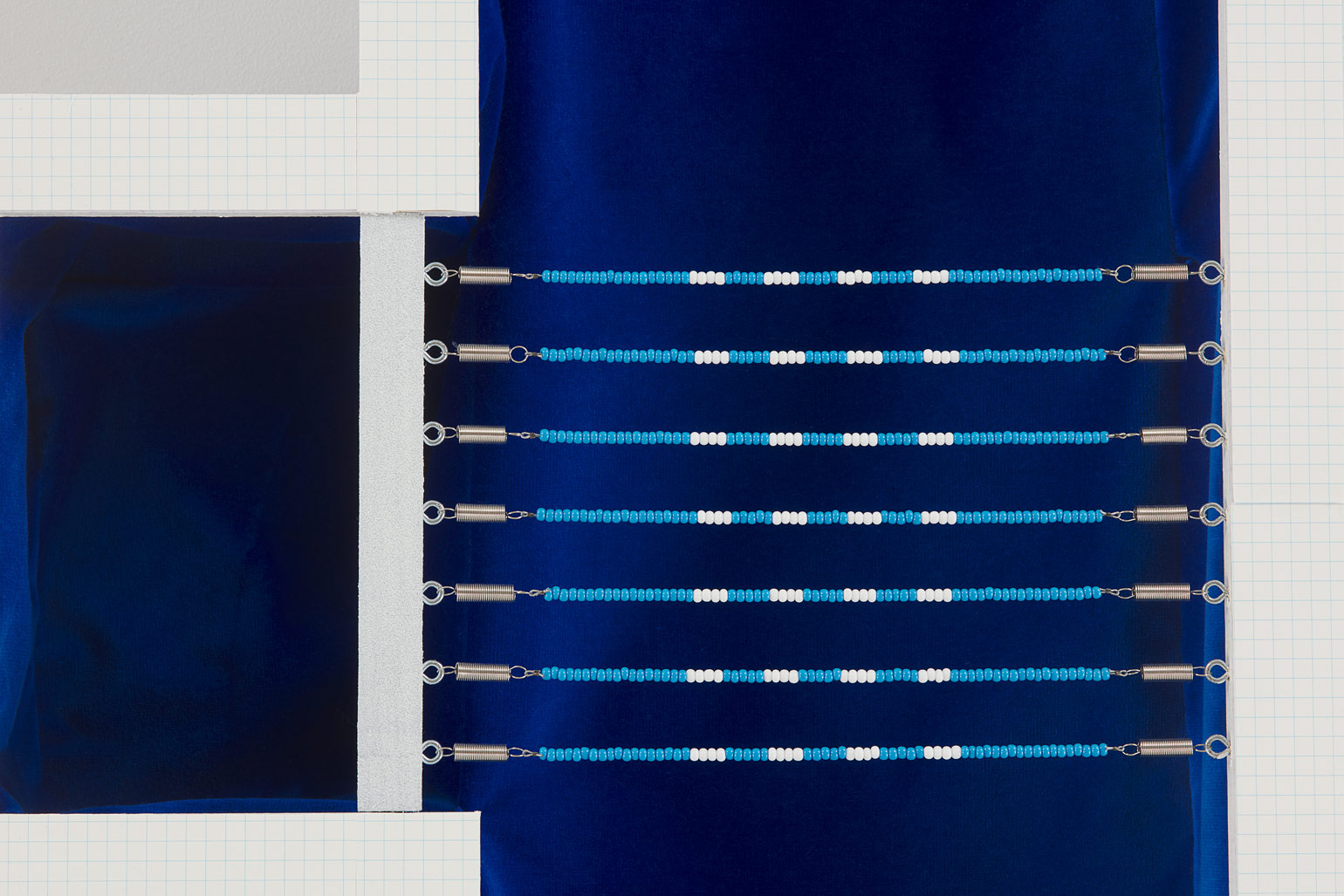

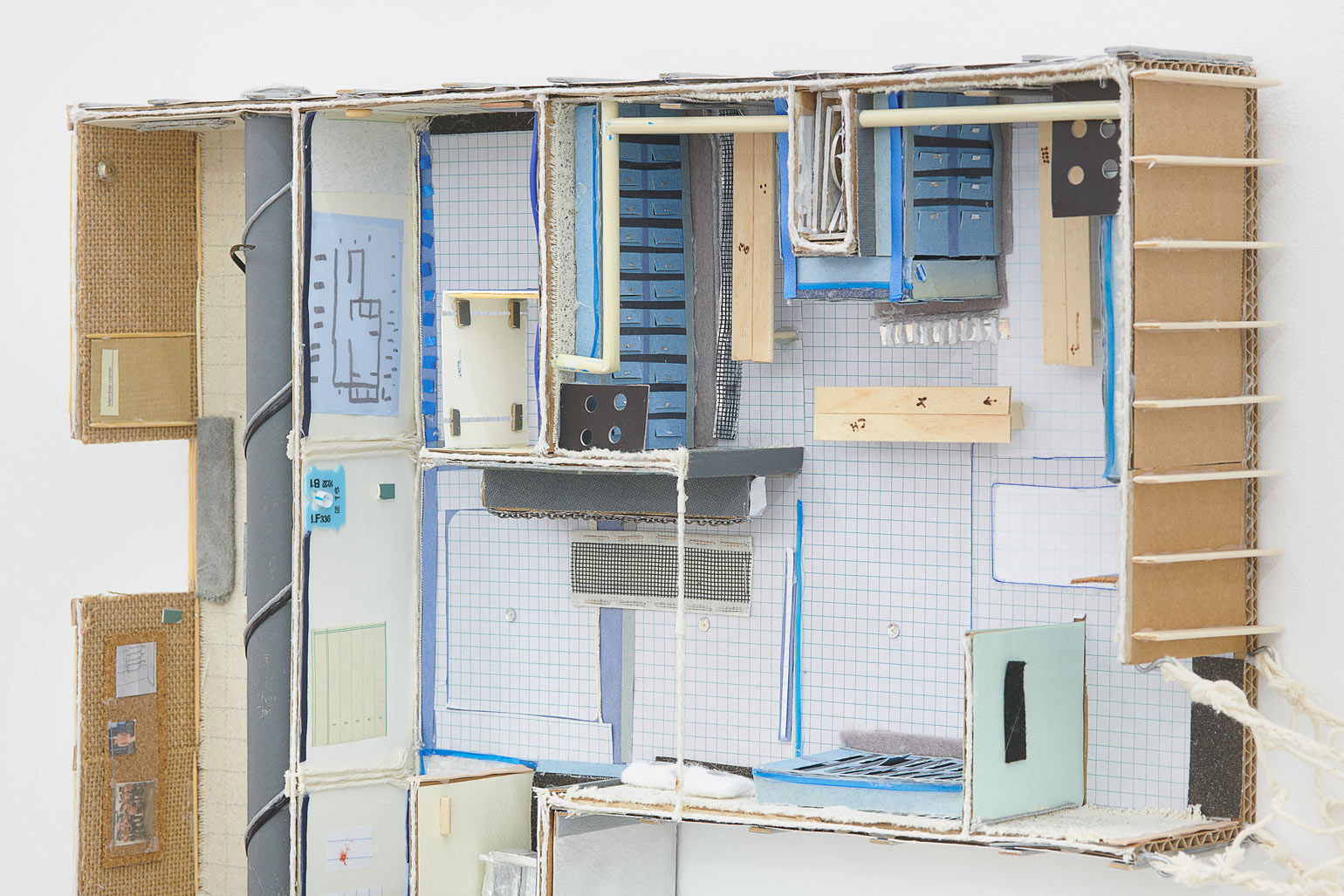

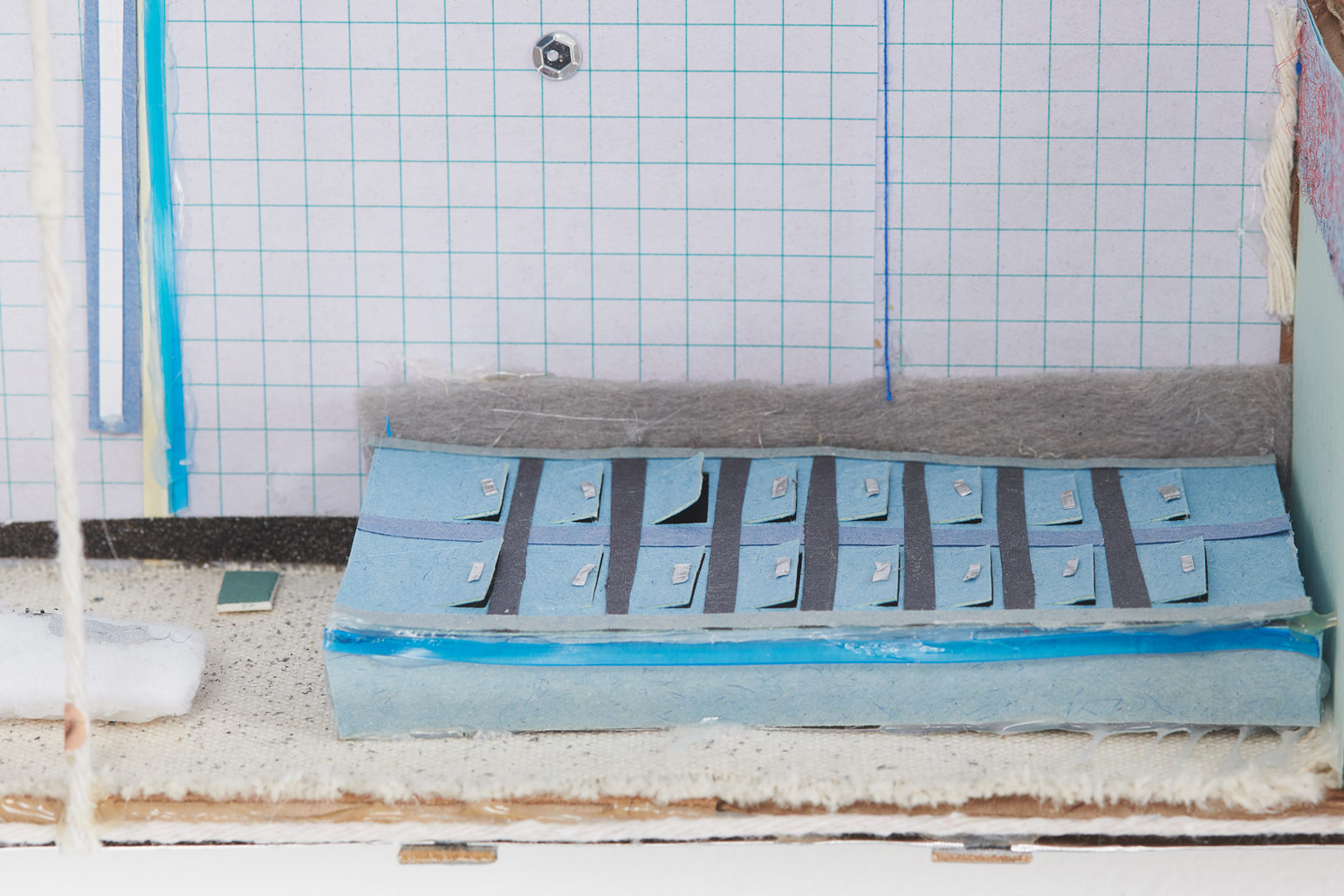

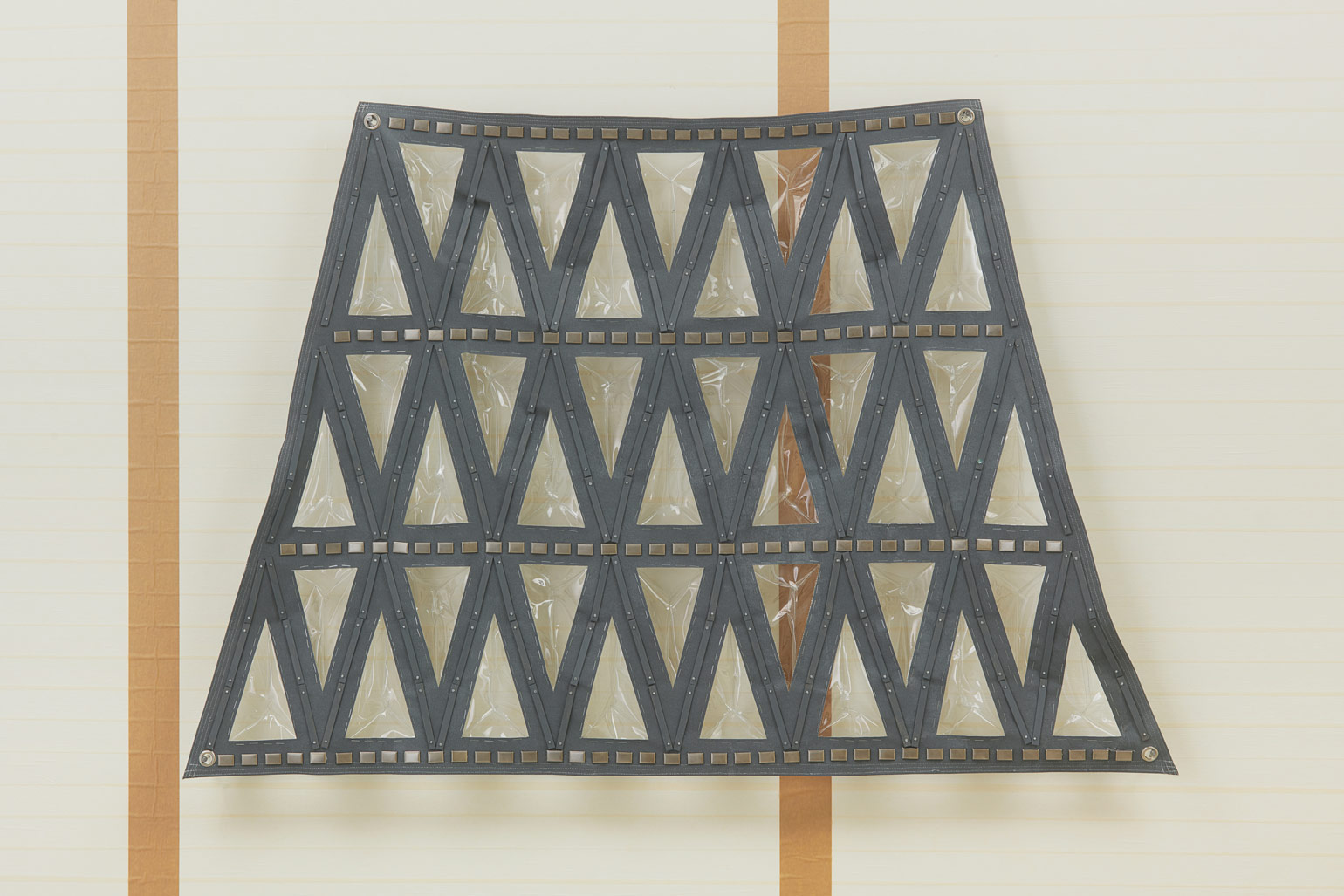

The artist has been crafting these excessively detailed works—or “handmade readymades,” as he sometimes calls them—for a few years now. Opting for proximal materials, most are culled from the recycling bin at his workplace, from the dollar store or hardware store on Davie Street in the gay village, or from the ground. While a number of imperatives could feasibly be tacked onto this impulse, it’s truer to say that Watt (who studied art history, not studio art) has always been doing this, led by insatiable curiosity, attention to detail, and maybe even a 6th sense. To spend any amount of time with him is to know his ability to unearth strange things in plain sight; his eyes are somehow always fresh. In thinking of Robert Gober’s doll houses, Hilton Als draws on an idea from Barthes: toys are designed in such a way that “the child can only identify himself as owner, as user, never as a creator; he does not invent the world, he uses it; there are, prepared for him, actions without adventure, without wonder, without joy.” Watt’s work, which collects many such “mainsprings of adult causality,” re-engineers our relationship to what’s given—not only destabilizing our position as “users” but also drenching the complex processes of identity formation in jouissance.

Calling such work “surrealist” is a lazy cop-out, remarks Als in the same essay, an overly general place to park practices that seem to draw their ideas “from thin air.” This observation underscores a generalized belief that outlandish concepts and configurations are not available to properly acculturated adults, or could only come when they’re sleeping, unaware. It’s consistent with the domestication of art into academia, wherein creative output is chiefly intellectual, and where form follows from dialectics, resulting in so much work that is conceptually neurotypical, politically conclusive, and experientially threadbare. By contrast, Watt’s oeuvre to date is like a cold plunge; “[d]esire is depsychologized” (Leo Bersani writes in the chapter “Is There a Gay Art?” from Is the Rectum a Grave and Other Essays), stripped down to something sensuous, hemic—although not primordial in the way that surrealism is either. In other words: a welcome reminder that modes of comprehension can be started from scratch.

As Bersani writes, visual art “can manifest what Greil Marcus calls ‘the mystery of spectral connections between phenomena separated by a conventional and restrictive perceptual syntax.” The queer mind might, on Thursday, exploit what’s conjured by markers of DIY theatre, kids’ crafts, and campy gay club décor; and, on Sunday, channel the spirit of elusive, minimalist women artists, squinting out at the desert. As Watt tells me: “When faced with aesthetic choices, I choose not to choose.” While the results may appear to some as an unflinching cognitive dissonance, getting inside this practice might be simple as slightly shifting one’s mind frame from either/or to both/and. As Watt puts it, the vision is singular, “but expressed tangentially through variation, mutation, chance, experimentation.”

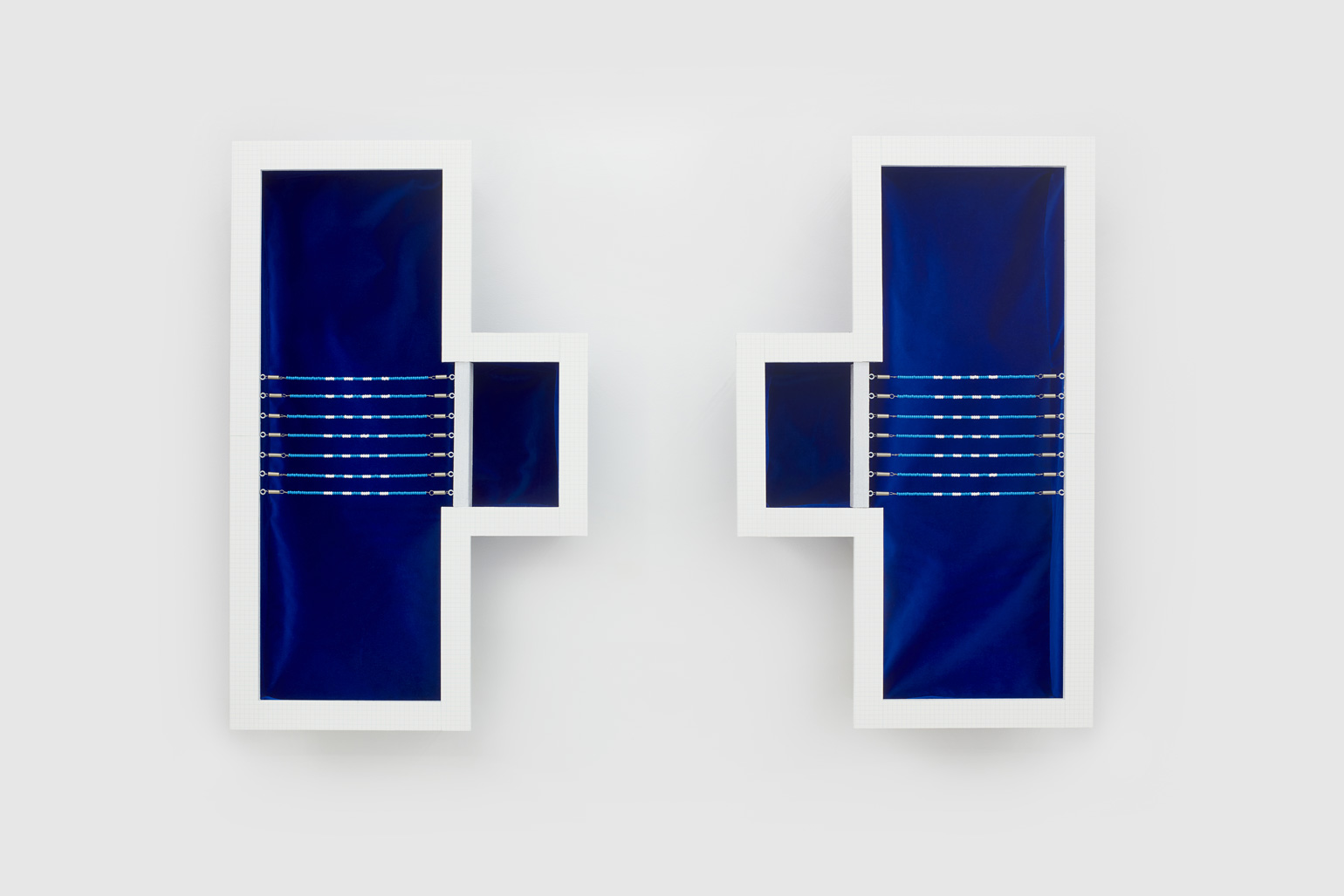

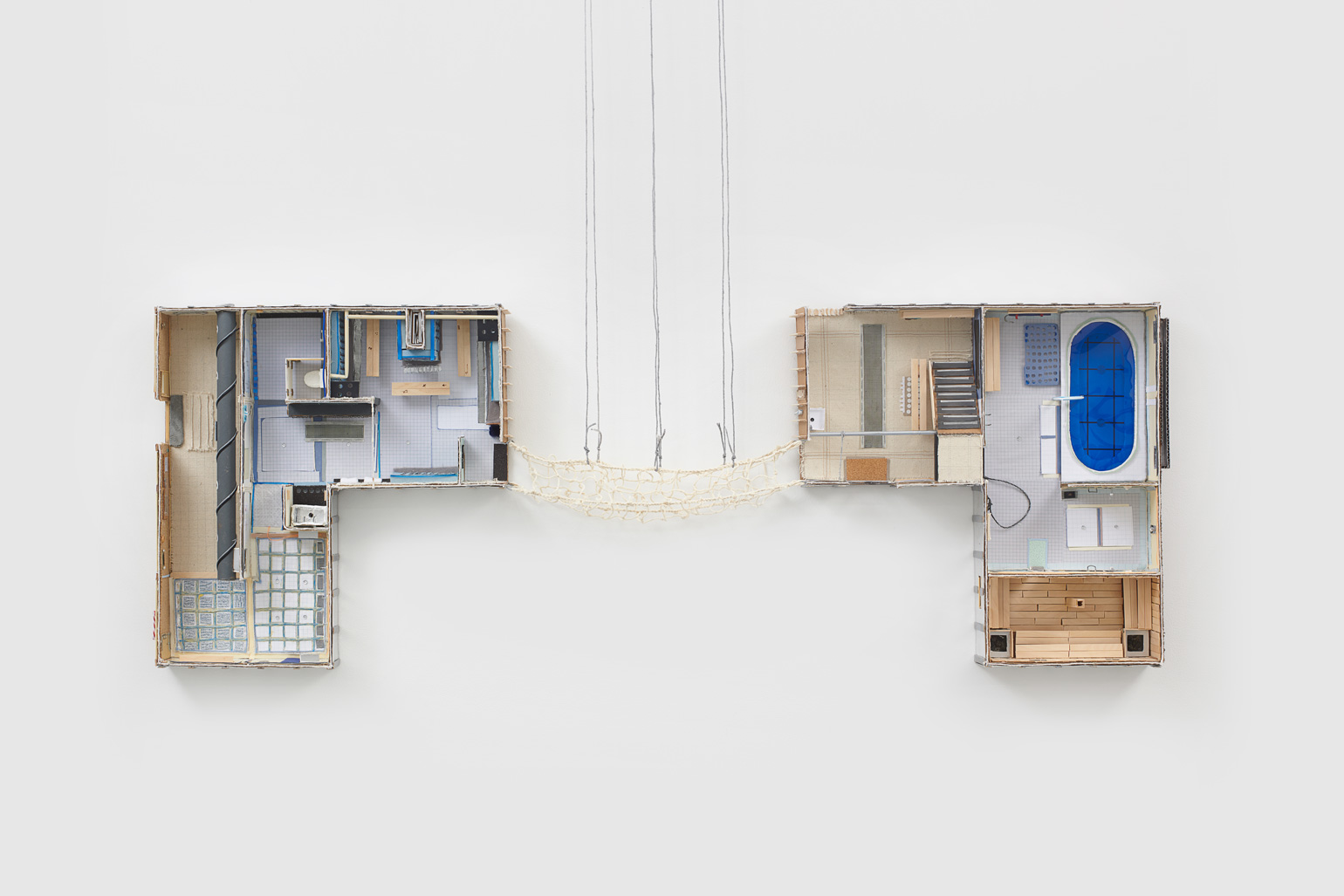

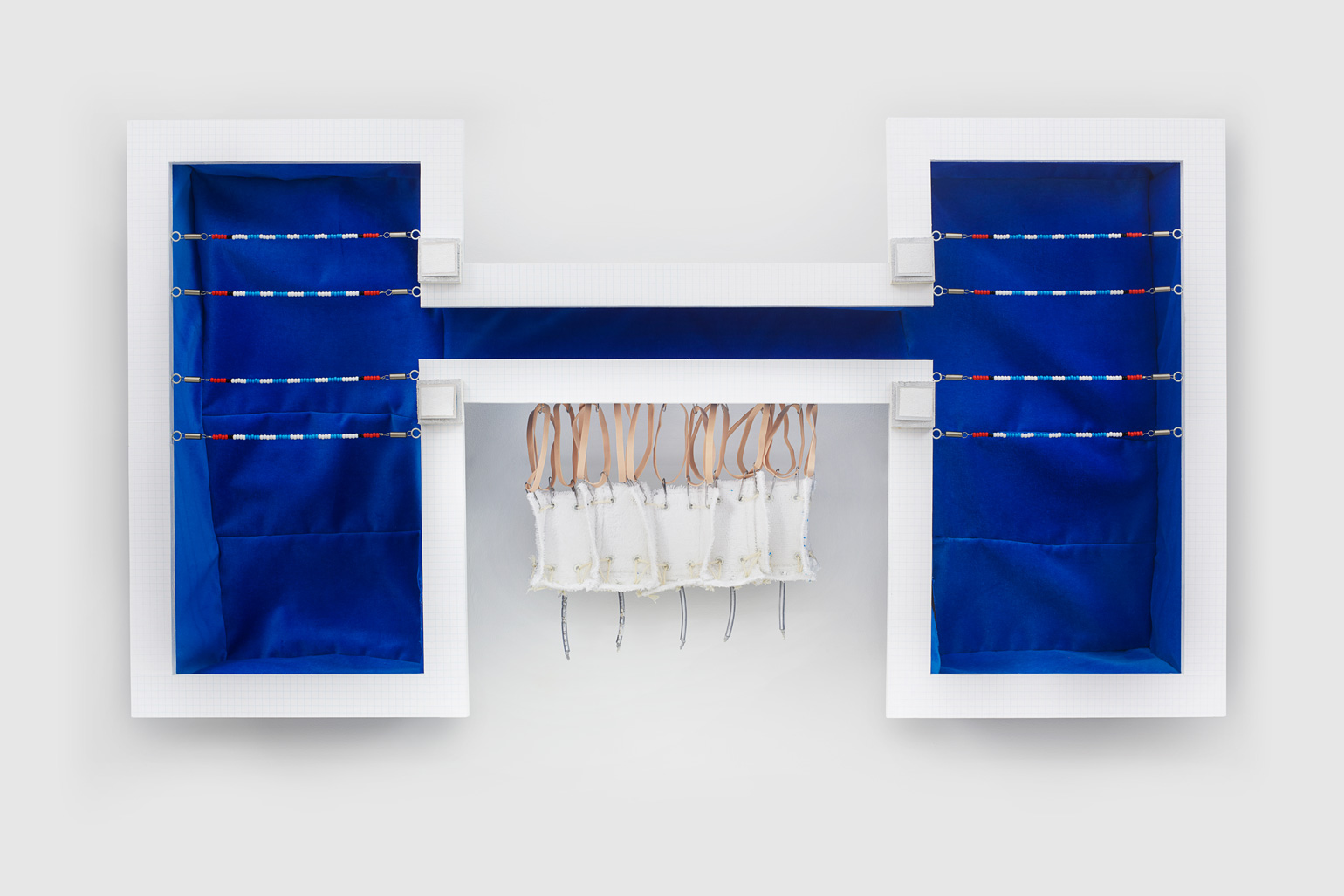

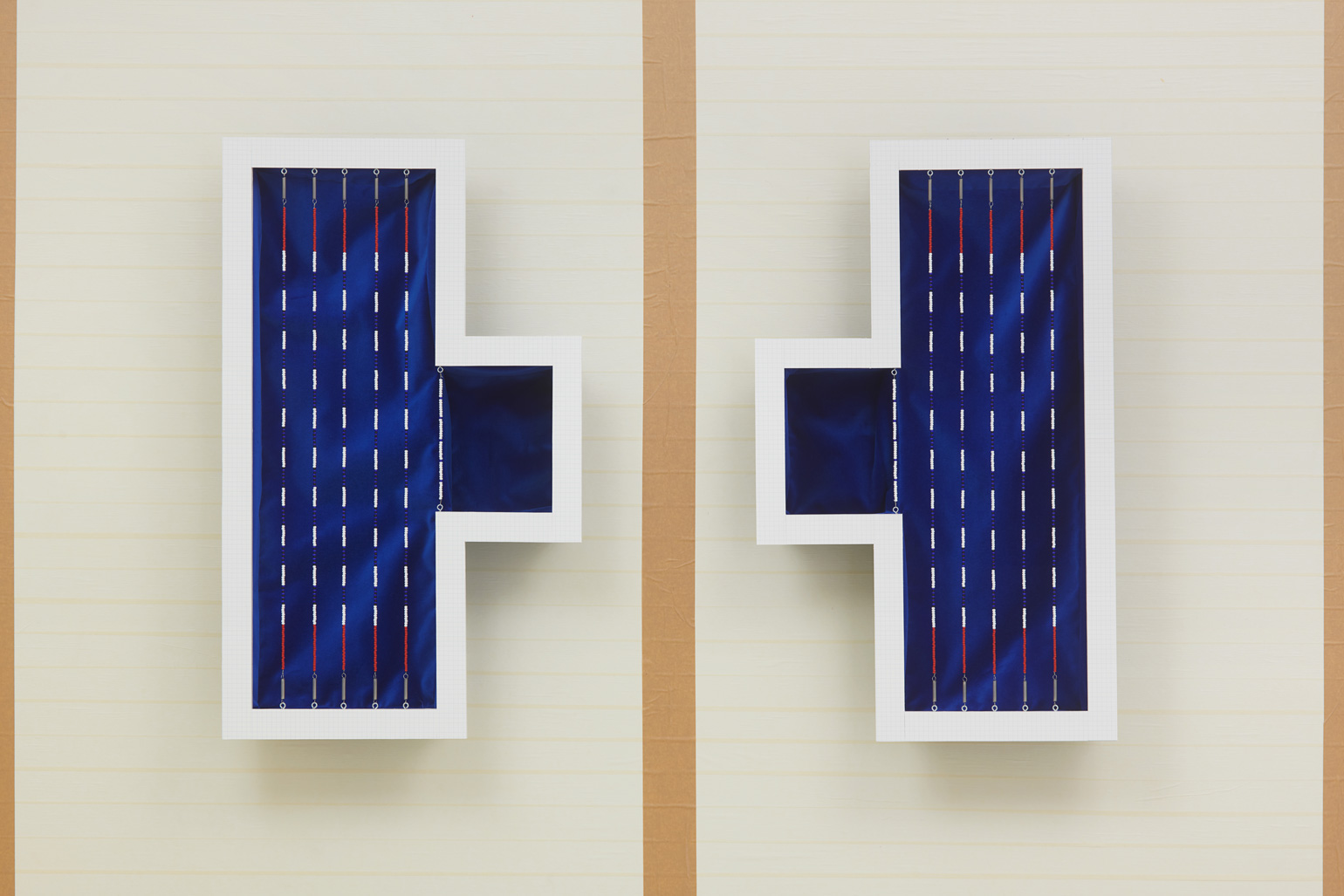

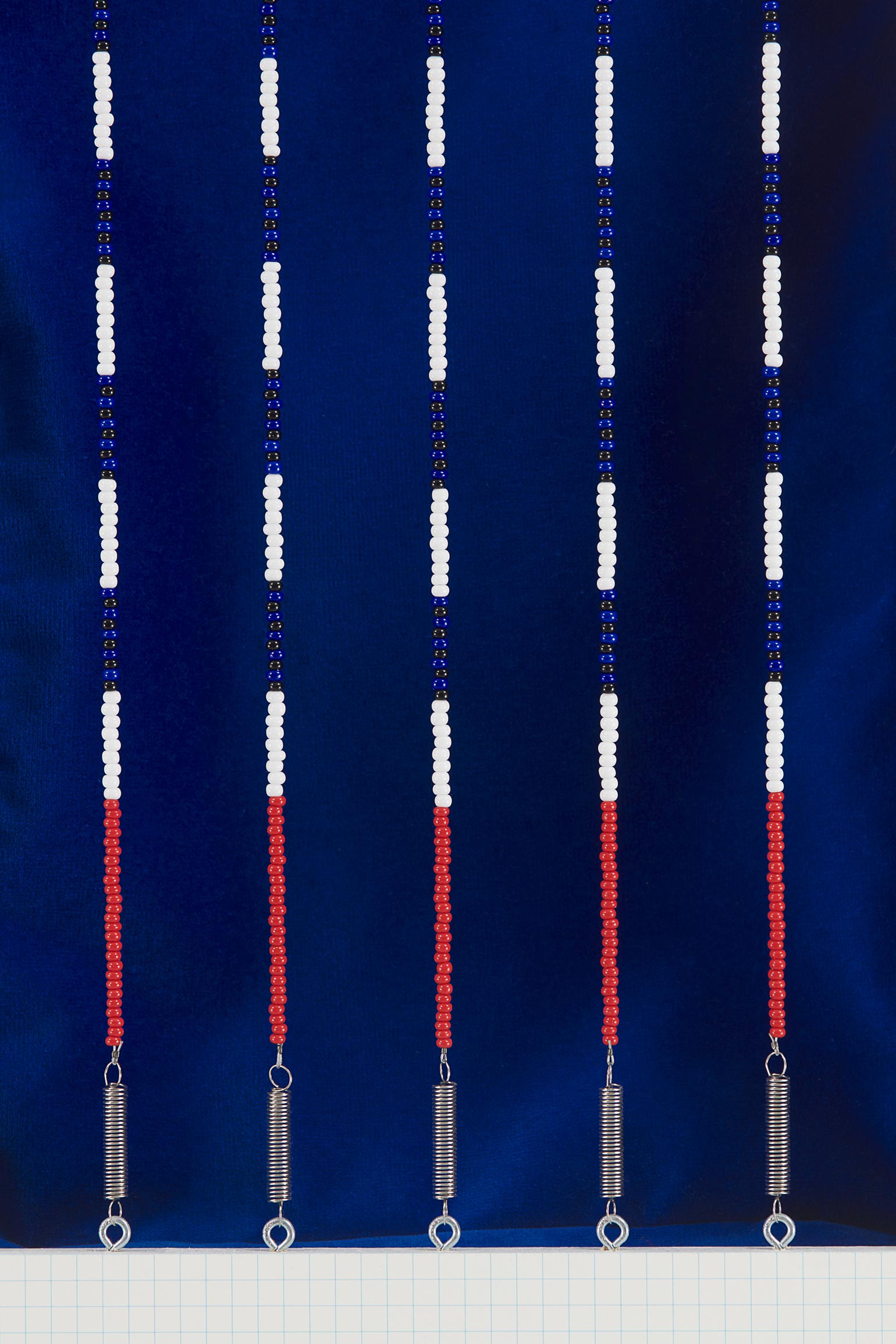

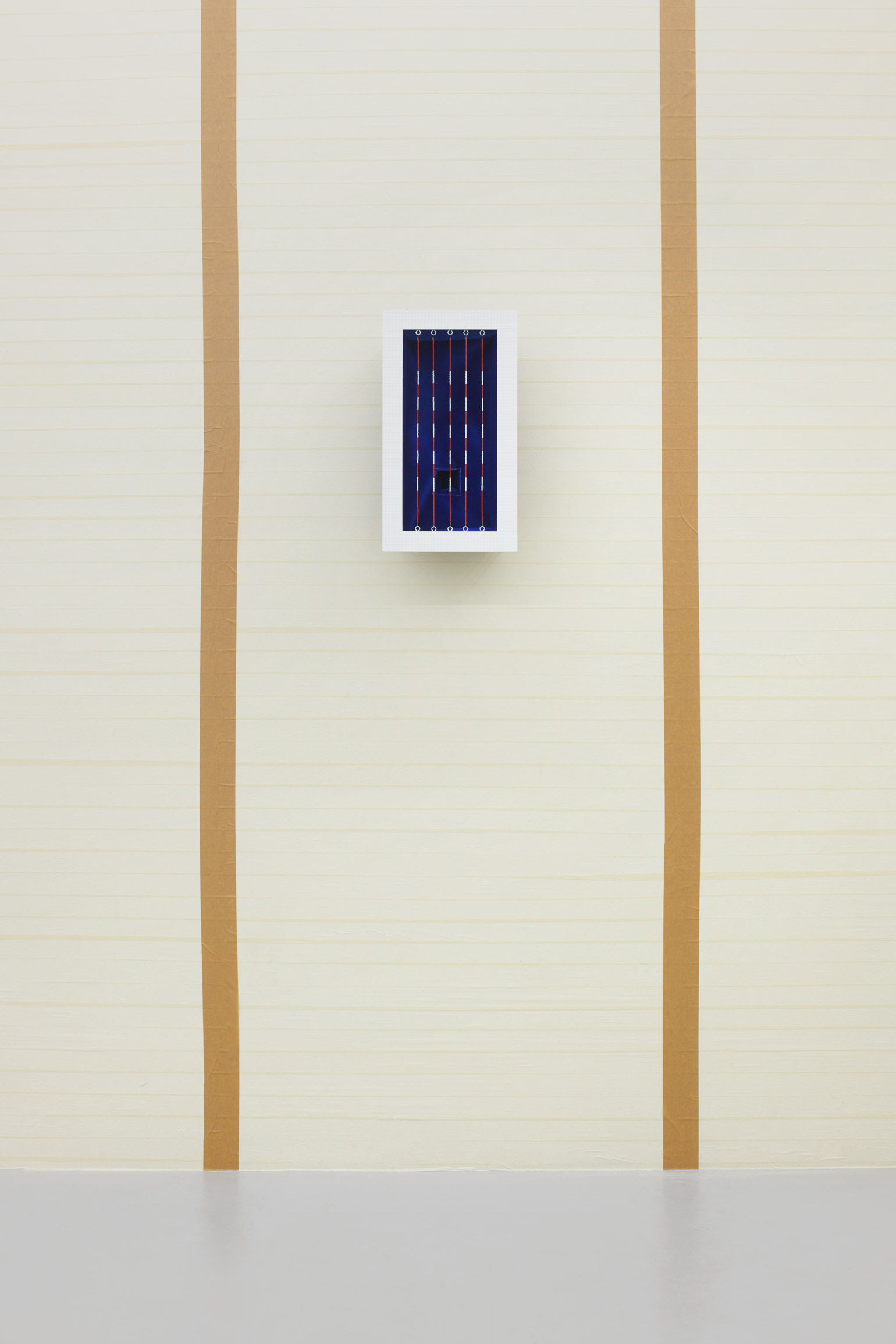

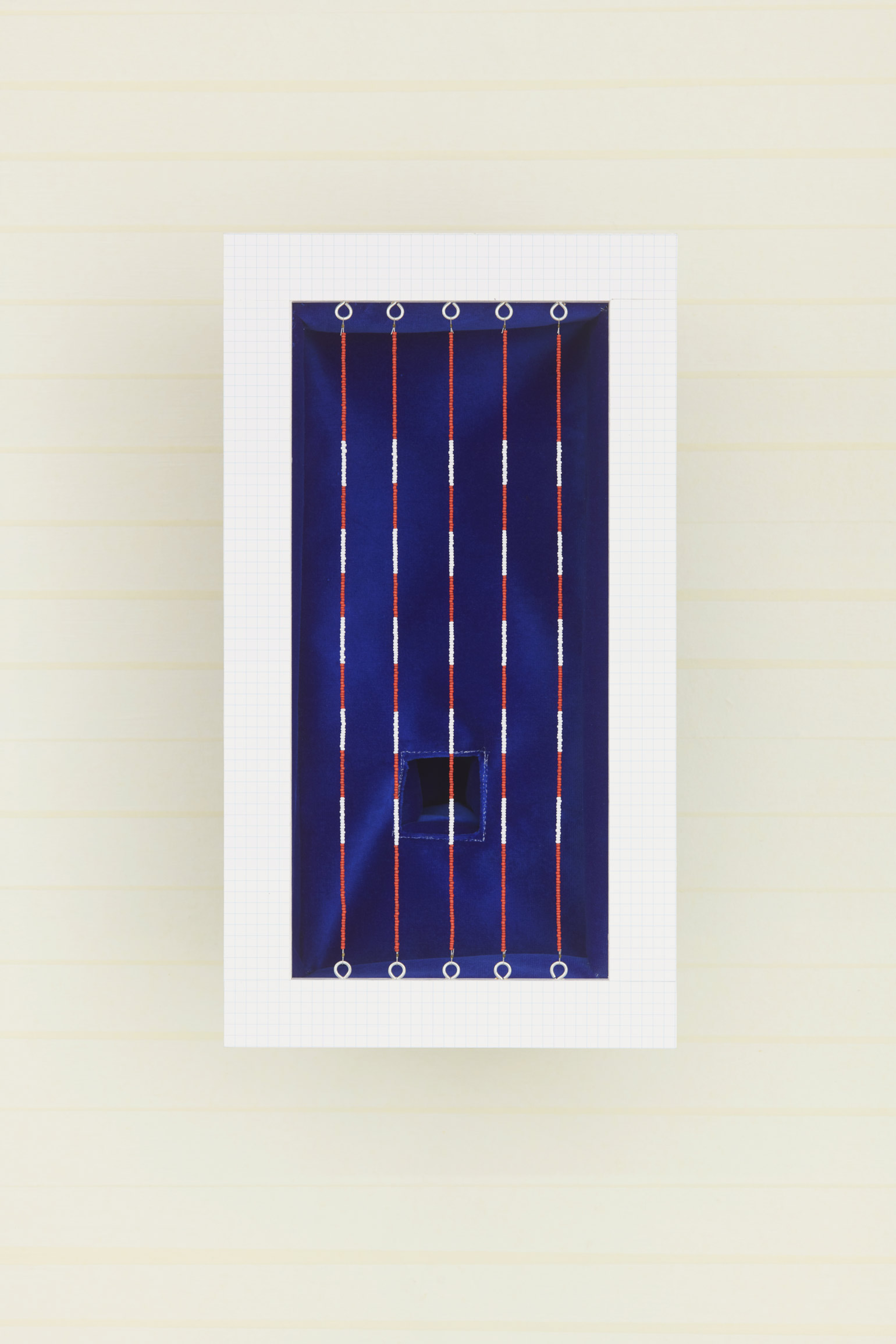

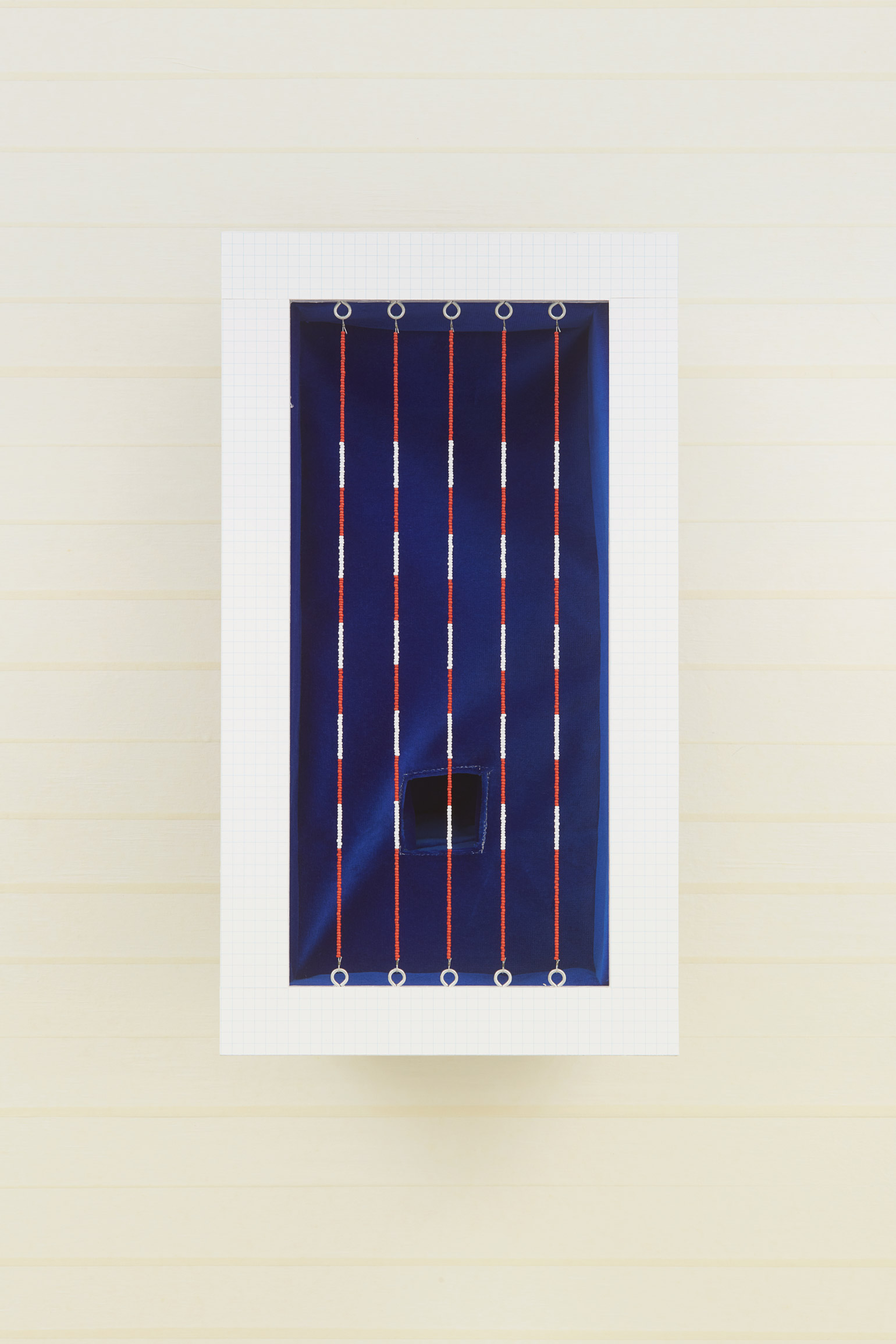

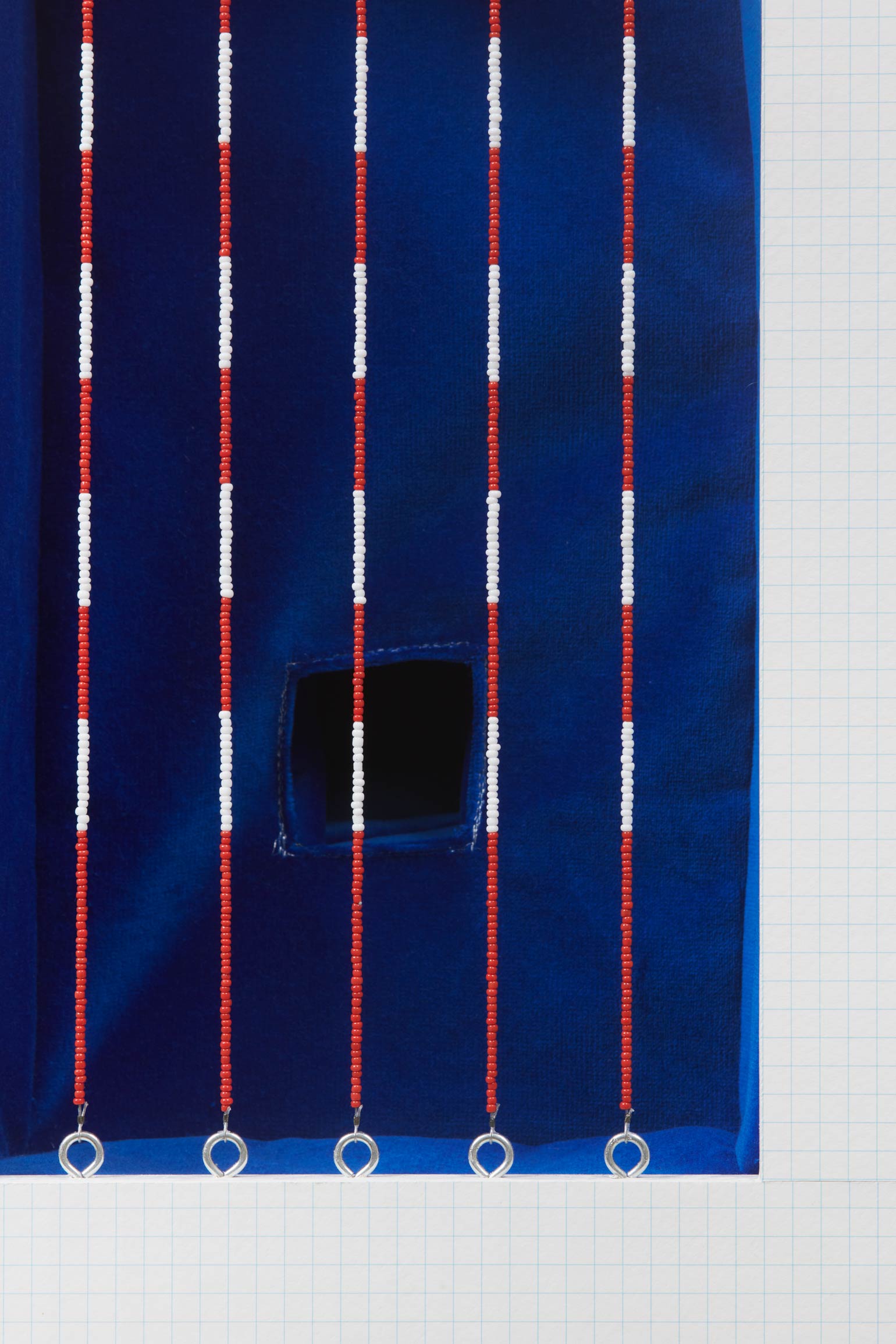

These heterogenous decisions around how in control the artist appears to be produce a bouquet of spindly arrows that allude to another question of control. Watt tells me he’s interested “in internal turmoil, epiphany, ecstasy, creative rushes experienced in ordered, manmade environments,” instantly invoking cruising, but more broadly highlighting a tension between excesses of feeling and spaces where expression is coded in specific ways—the swimming pool being one such example. This new body of work might be thought of, then, as an experiment in reproducing that tension for the viewer; a kind of edging. As Marianne Moore wrote: “The deepest feeling always shows itself in silence; / not in silence, but restraint.” The exquisite, sharply geometric pools, lined with blue velvet and replete with identical hand-beaded lane dividers are of course small replicas of life-sized swimming pools that are themselves simulations of natural swimming holes, with their dark floors, bottom feeders, weeds, and leeches. The architectural pool seeks to provide comparable refreshment, exercise, and leisure without danger, or as Watt put it: “total transparency and no consequence.” But even in the most iconographic works, to literally lean in towards the wall, behind the velvet, is to find something unsettling after all—infinitesimal, mostly out of focus signs of things amiss, or in progress, or forgotten, or tangled, or private.

If this show were a person, they’d be lambently present but unknowable, one to leave a mysterious stain after brief, chasmic interactions—not unlike Watt himself, actually. The simultaneous desire and inability to rectify the works’ opacities spur speculation, theatrics, and roleplay. Riffing on Lee Edelman’s conception of queerness not as an ontological condition or identity category but as that which cannot be assimilated into the aesthetic (“the obscene remainder”), Deep End Epiphany might be considered an anti-essentialist engine that stirs suspicion of all facades. The quiet is charged by disquiet. Like a bubble from below, Ivan Illich’s conception of water slowly surfaces: “the fluid that drenches the inner and outer spaces of the imagination. More tangible than space, it is even more elusive… ”