Kim,

I was surprised to learn that “permaculture” is a portmanteau for “permanent culture.” This permanence is one not of essentialized fixity, but achieved through the ongoingness of doing— a flexible system that ensures sustainability. I’ve spent quite a lot of time during the last few years grappling with what it means for me to be a culture worker in this place and this time. I was doubtful about the possibilities of this culture work being either very fruitful or sustainable.

In a transnational collaboration that obliquely resonates with our own biographies, Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei Shih, respectively a Mauritian-French scholar in African American studies and a Korean-born Chinese working in Asian American studies, open their co-edited volume Minor Transnationalism with a co-authored text that encourages a shifting of attention to encounters among diasporic subjects:

“We realized, in retrospect, that our battles are always framed vertically, and we forget to look sideways to lateral networks that are not readily apparent… The dominant is posited, even by those who resist it, as a powerful and universalizing force that either erases or eventually absorbs cultural particularities.” (1)

Looking sideways is effortful. Your Chinatown (2) is qualified by Paris, this one by New York. How seemingly impossible it is to tear the attention away from the colonial histories that name and shape these places.

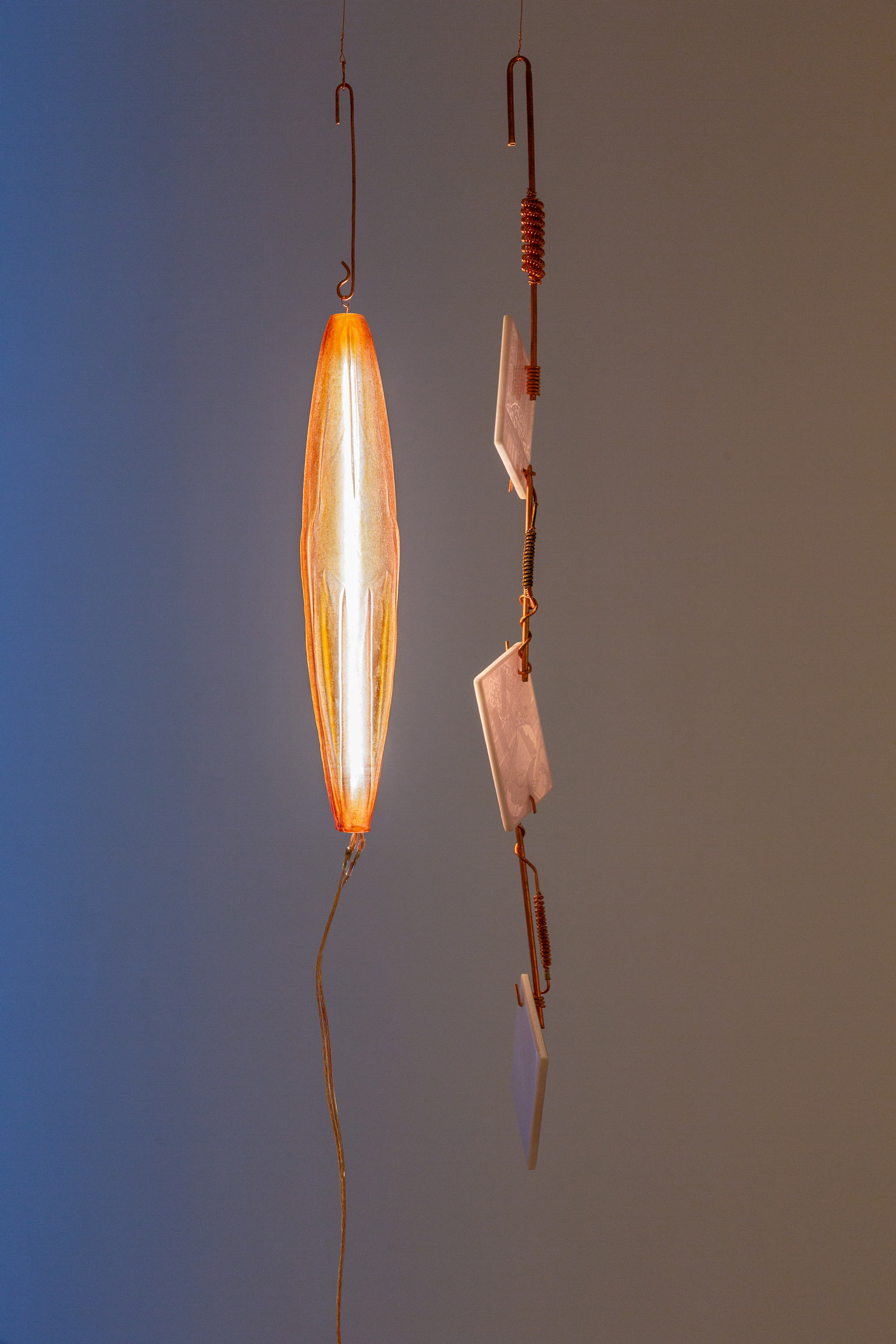

Looking sideways is effortless. Diaspora is a practice that is always already hybrid, in dialogue, in translation. As you’ve told me, the « témoin lumineux » is an indicator light that says, “We’re still here.”

Who is the we, though?

In the introduction of Orientalism, Edward Said quotes from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks: “The starting point of critical elaboration is the consciousness of what one really is, and is ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical process to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory... therefore it is imperative at the outset to compile such an inventory.”

The ability to refer to the “we” of an ethnic group has its uses, particularly when the “we” has been rendered elusive by complex histories of colonization, diaspora, displacement, and erasure.

As you know, the name for your maternal ancestors, the Peranakan, has shifting meanings depending on the context of its usage. It points to both people and place—“descendants of” or “from the “wombs of,” but I’m most drawn to its connotations of “locally born but non-indigenous” and “hybrid.” I also recently learned that the word “diaspora” was originated to refer to your paternal Jewish ancestors.

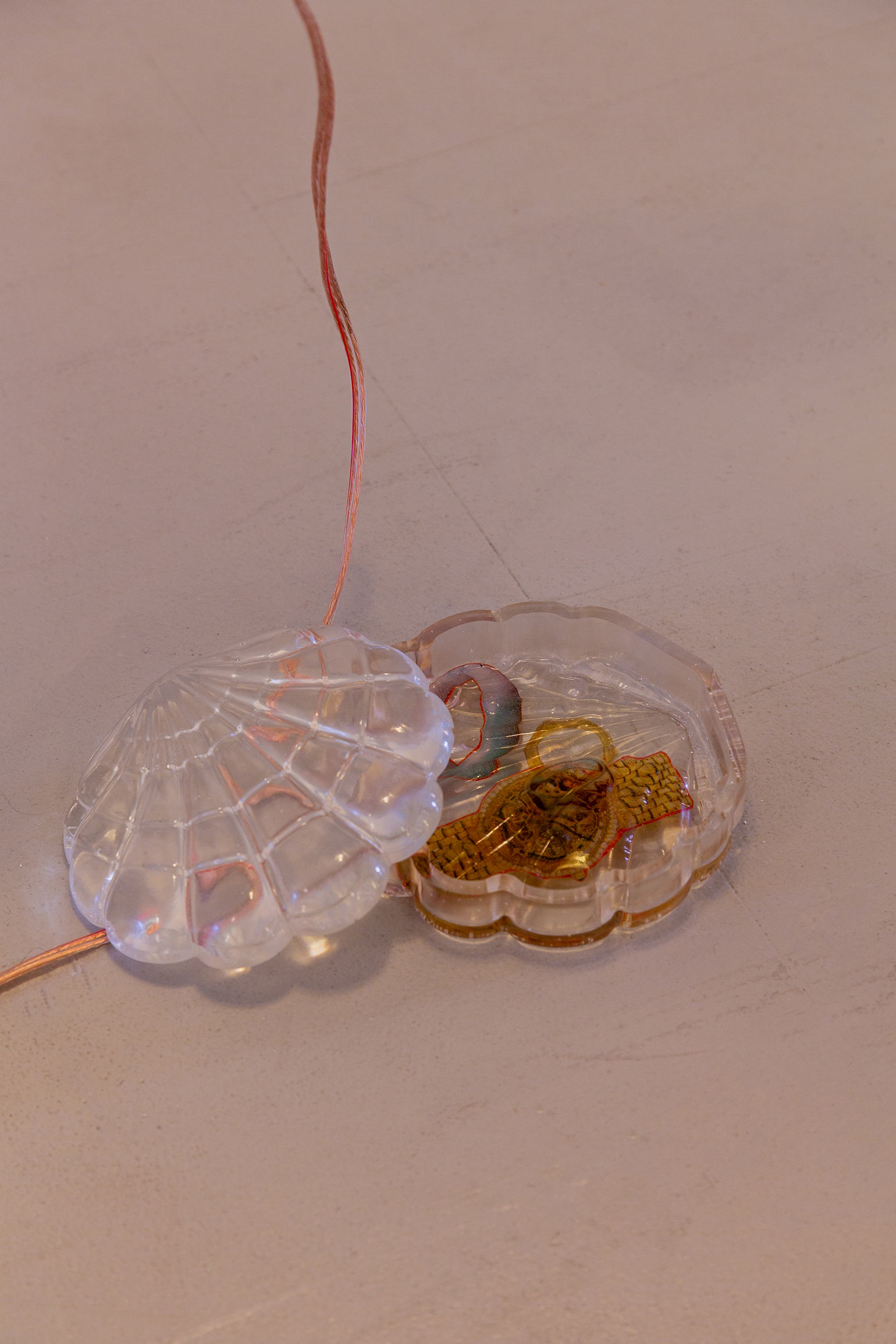

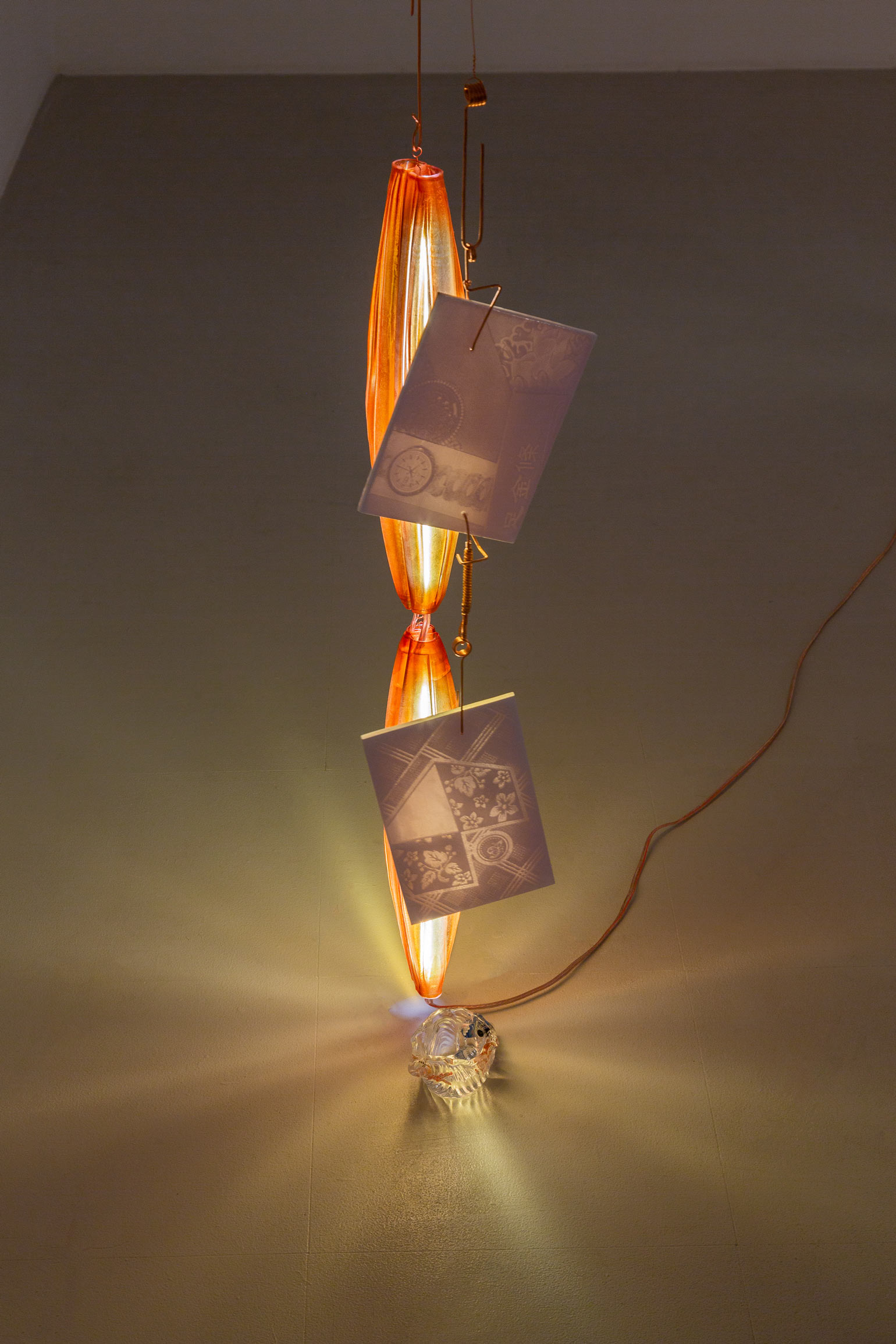

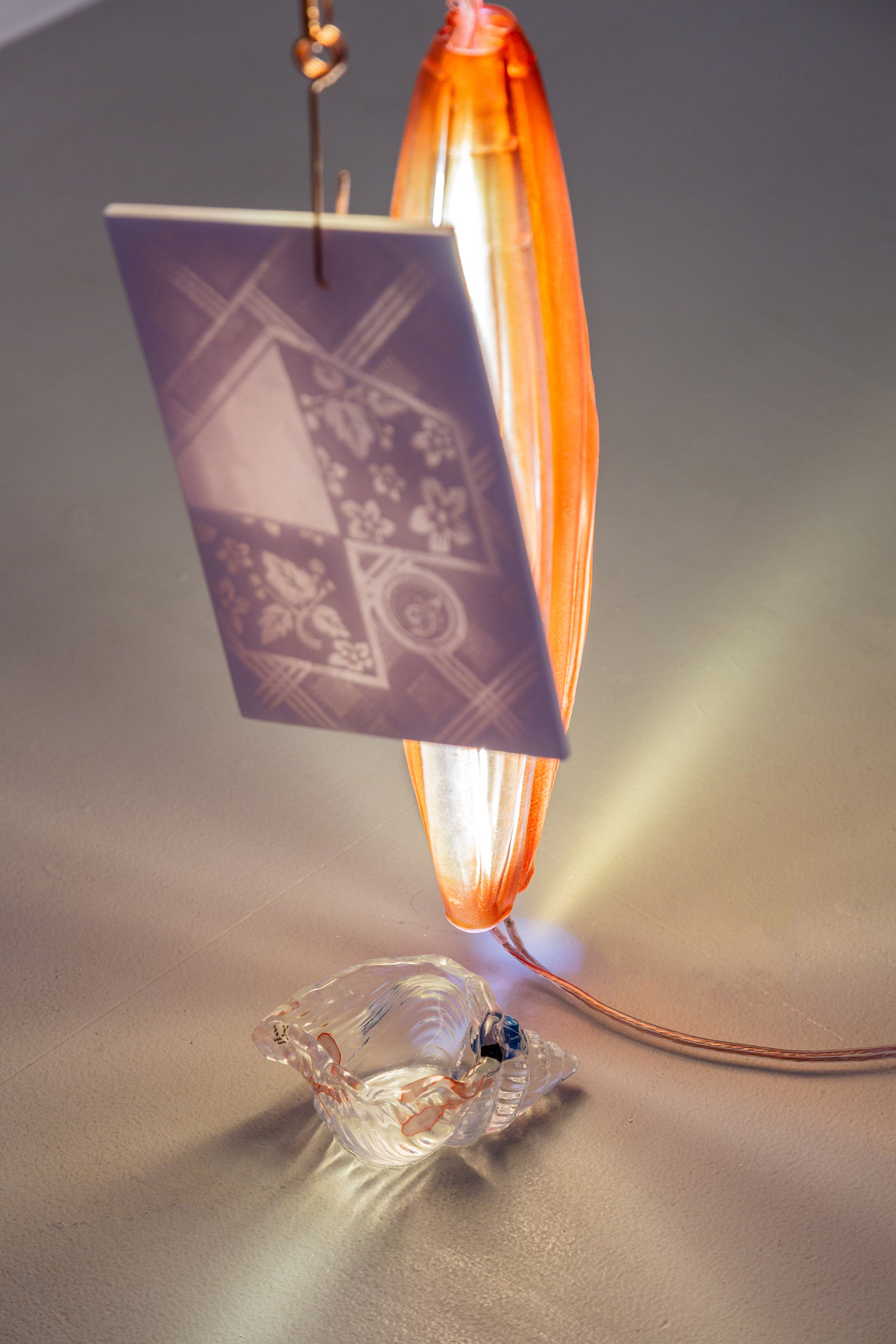

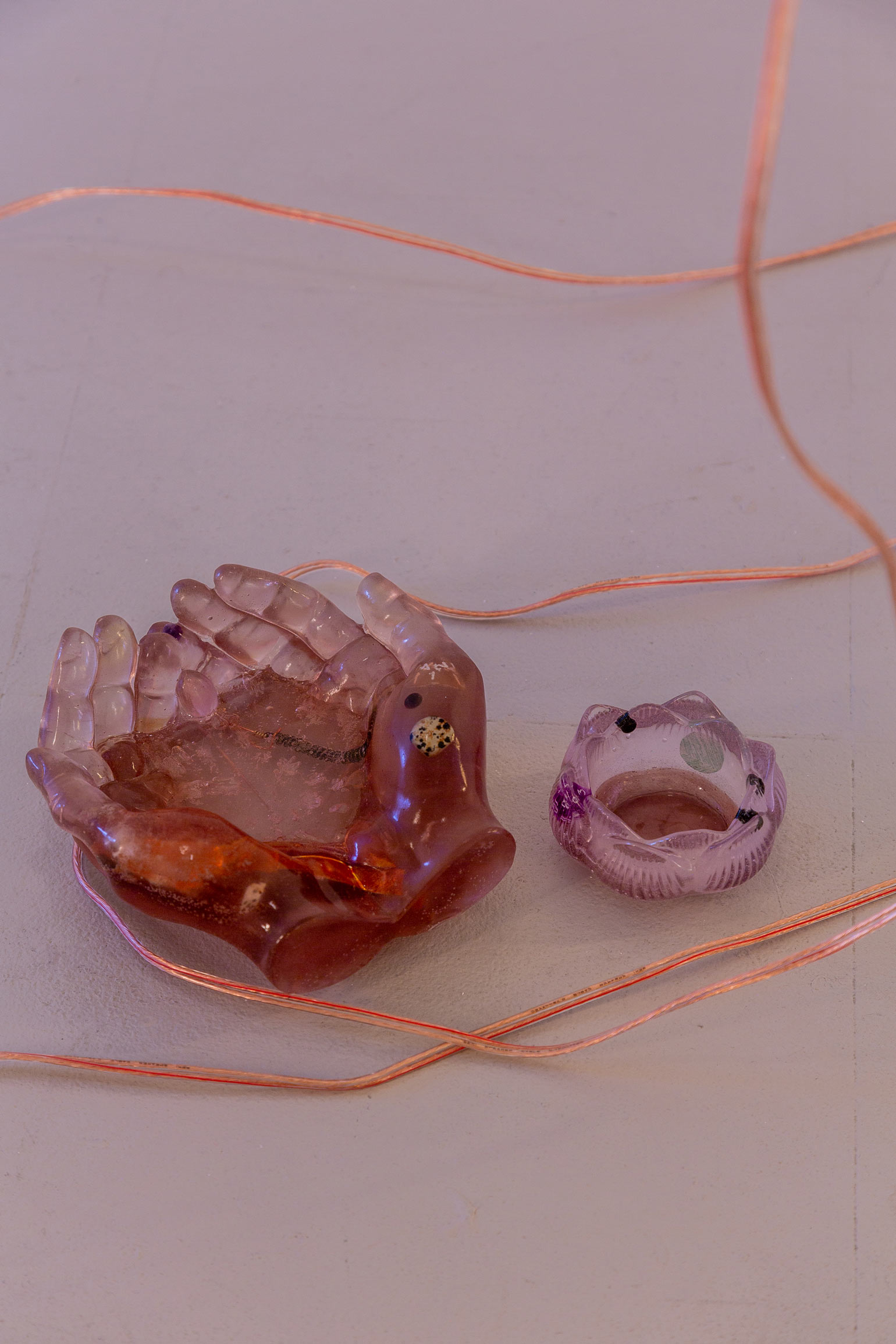

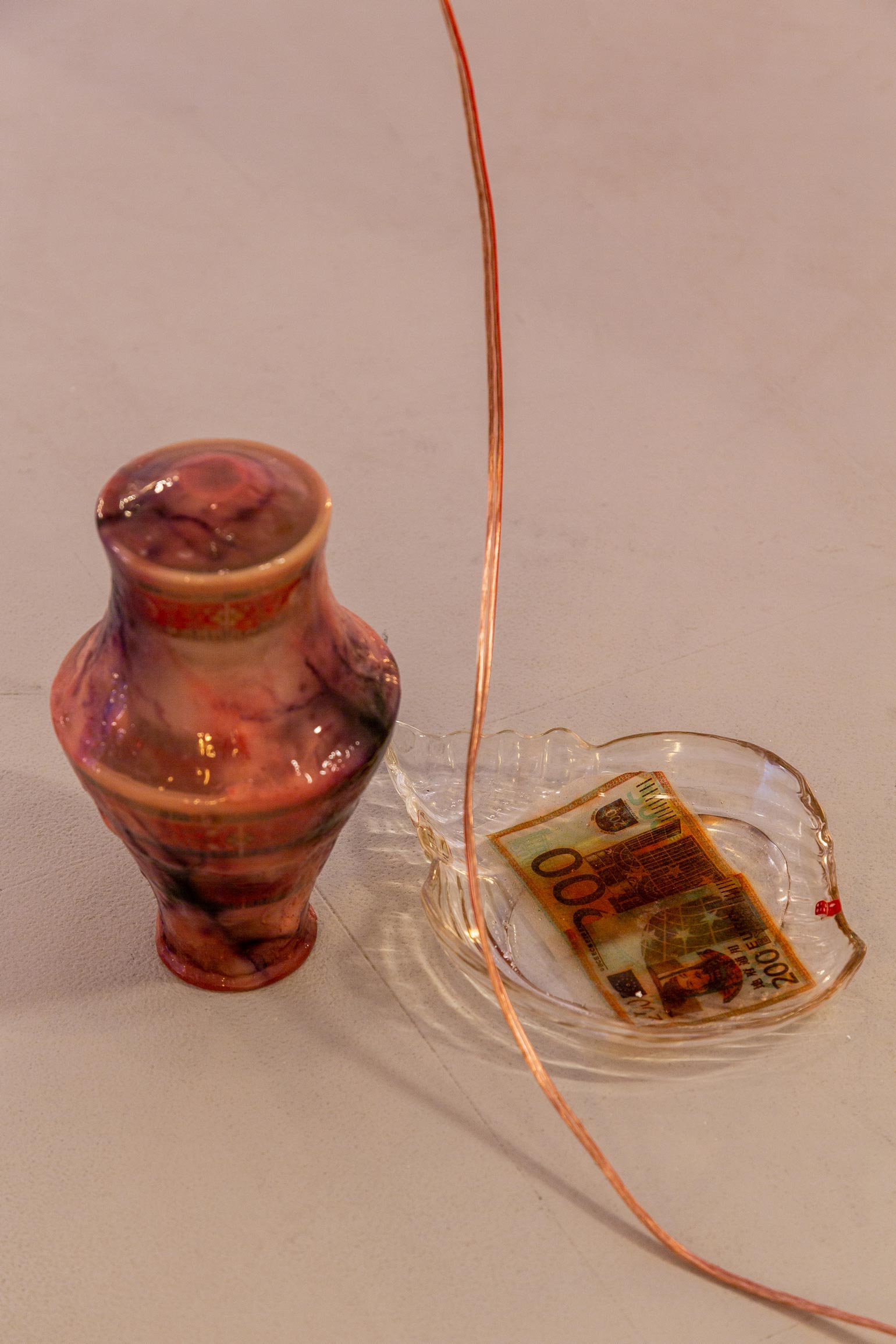

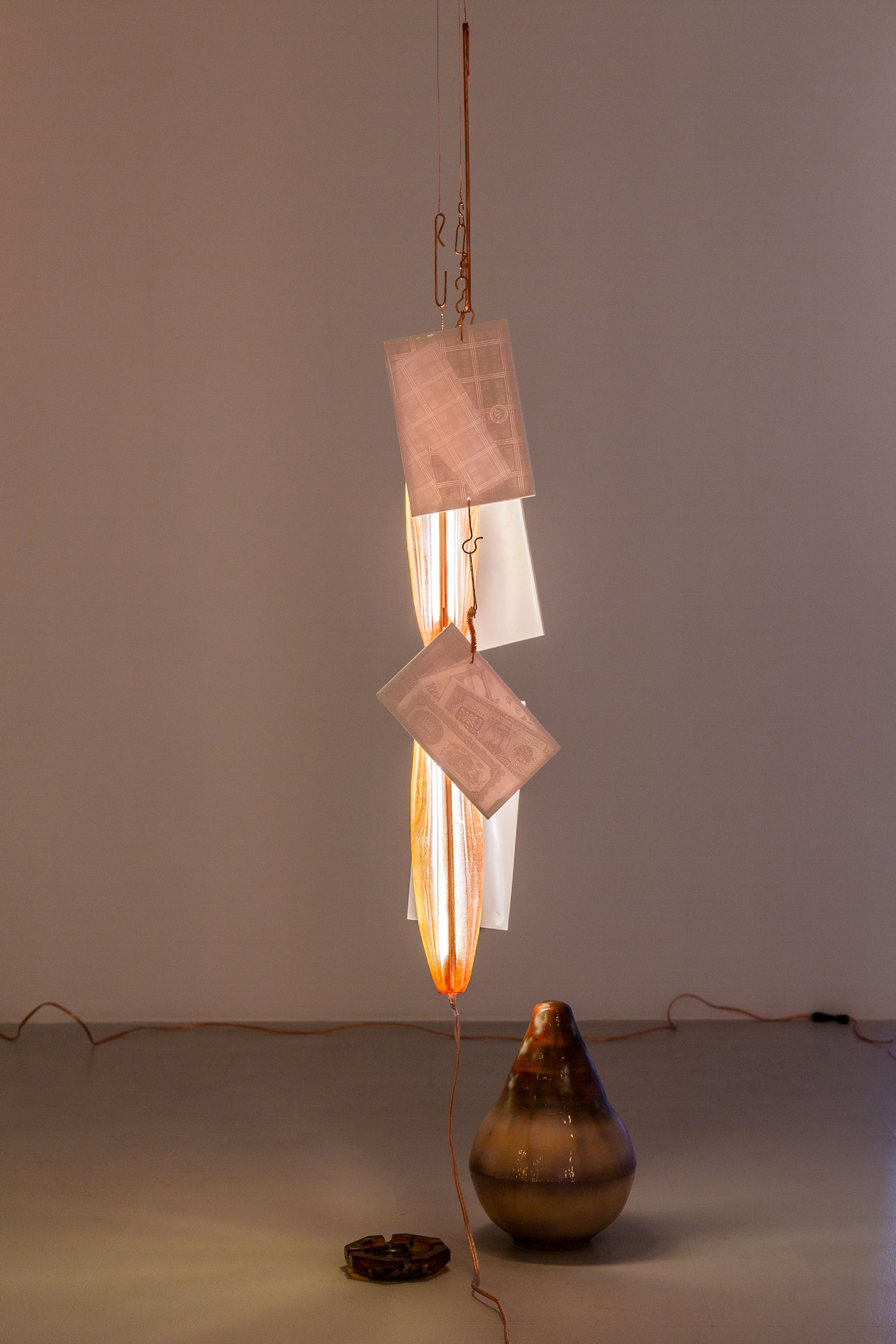

The resin in your work has also always been a kind of témoin, testifying to the materials and technologies of our time, collapsing traces of your forebears and kindred spirits into an inventory for those to come. I think of this work as permaculturally Peranakan—an evolving system that collapses disparate geographies, time periods, and corresponding shifts in relationship to objects, codes, and practices. Lionnet and Shih also refer to a “politics of retrieval,” gestures through which the diasporic subject grapples with authenticity and a return to a culture made distant through assimilation. We—you and I, diasporic culture workers, minor transnationals—work with what we have at hand. Our participation might be weighted towards the center, but continues sideways through strain, through instinct, through those who call our attention to the point of entanglement that is the elsewhere.

I’ve chosen the epistolary format to respond to Permaculture because this writing is just that: one momentary response in an endless process of encounters. I’ve been returning to a line from Fred Moten’s Black and Blur in which he describes “a reconfiguration of the concept of writing as that which occurs where performance and recording converge at the site of a bodily inscription.” (3) Correspondence, like your custom composites, is a particular kind of inscription, which perhaps more readily reveals the convergence of bodies and the written word, disturbing staid understandings of producer and produced.

I know that what has been vital for you has never been simply the objects of production, but the systems that produce them that go more or less unseen. If what is made is an occasion for more lateral encounters, even if they are uncomfortable, then I think culture is performing as it should.

Looking at you sideways, from over here, as always

Ana

1 Lionnet, Françoise., and Shumei Shi. Minor Transnationalism. Duke University Press, 2005

2 In an American conversational context, I do refer to the neighborhood where Kim lives in Paris as one of the city’s two “Chinatowns,” though in French they traditionally have not had proper names, but rather descriptors: « les quartiers chinois » or « les quartiers asiatiques ». A campaign to rebrand as Chinatown Paris is underway. From my vantage point in Los Angeles, I am unsure whether to read this campaign as an act of self-affirmation of a diasporic Chinatown culture, or as a vehicle of gentrification. Perhaps it is both.

3 Moten, Fred. Black and Blur. Duke University Press, 2017.

...

金:

当知道 “permaculture” 这个词是 “permanent culture”(恒久文化)的合并词时,我吃了一惊。这种恒久在本质上并非与生俱来,而是经过持之以恒的努力得来的,这是一个为保证其持续性而相当灵活的语系。前几年,我花了不少时间苦苦思索:此时此地作为一个文化工作者,这对我有什么意义。我曾怀疑过这种文化工作是否能够富有成效,或者是否能够存续长久。

在我们自己的传记中,或多或少反映了一种跨国主义的合作。李欧旎和史书美,前者是毛里求斯法裔法语语系学者,后者是出生在韩国的华裔华语语系及亚美研究学者,他们合编的《弱势族群跨国主义》I 一书以下面这样一段共同撰写的文字开头,鼓励人们在关于离散的诸多话题中,把注意力转移到文化邂逅:

“回溯既往,我们意识到我们的斗争总是局限在垂直的框架中,我们忘记了转眸侧视,去看一眼并非那么显眼的横向网络… 主流已然被奉为,甚至被其抵制者承认是一股强大而无所不在的力量,文化的特殊性不是被其抹杀就是最终被其吸纳。”

转眸侧视需要努力。您的 “唐人街”ii对于巴黎来说没错,而这里是纽约。怎么可能脱离赋予这些地名和塑造了这些地方的殖民历史呢。

转眸侧视不费力气。在谈话和翻译中,离散是一种已然混合的说法。正如您告诉我的那样,

« témoin lumineux » 是一盏信号灯,表示说: “我们还在这里”。

那么“我们”是谁呢?

在《东方主义》一书序言中,爱德华 · 扎伊尔德引用了葛兰西《狱中札记》里的一段话:“批判性阐述的起点是对自我的真正意识,以及‘了解自己’是历史过程迄今为止的产物,在您身上沉淀了无穷无尽的痕迹而无从盘点。因此必须打一开始就编制一份盘点清单。”

能够将一个族群称为“我们”自有其用处,尤其是当“我们”被错综复杂的殖民化、离散、流亡和抹灭搞得扑朔迷离、难以捉摸的时候。正如您所知,您的母系祖先名称”娘惹”。其含义随着其使用的情境而不同。它可以指人,也可以指地点, 即“某某后裔”或“某地出生”,但是我更倾向于接受“本地出生但非土著”和“混合种族”的说法。最近我还得知,“离散”一词系源于对父系犹太祖先的说法。

您作品中的树脂也始终是一种提示,见证我们时代的材料和技术,将您的忍让和善良精神汇聚到留给后人的清单中去。我认为这件作品属于恒久文化的娘惹语系,一种在演化过程中融汇了地理、时期,以及随着与目标、规范和实践的关系而转移的语系。李欧旎和史书美还提到了“回收的政治”这是一种姿态,通过这种姿态,离散者验明正身,透过同化来回归前已疏远的文化。我们 – 您和我,作为离散文化工作者、弱势群体跨国主义者,竭尽我们的能力工作,我们的参与可能是朝着中心前进,但却继续因压力、直觉、经人指点要避开别处的障碍而走偏。

我选择用书信体的方式来对 “permacultutre” 一词作出回应。因为这种写法只是在无数次文化邂逅过程中的临时应对之举。我想到弗莱德 · 莫顿所著《黑色与模糊》一书中的一句话,描述“将写作的概念重新构建为写作和记录在实际铭文中的交汇”iii。通信就跟您的定制复合材料一样,是一种特别的铭文,也许能够更好地揭示正文与所写词语的交汇,颠覆制作人和作品的刻板理解。

我知道,对您来说最要紧的从来不只是制作目标那么简单,而是要产生一个其目标多少令人难以捉摸的系统。如果做到了创造一个实现更多横向文化邂逅的机会,即使它们令人感到不适,我认为文化已经尽到责任,达成了它的使命。

一如既往,我在这里盼望着能得到您的侧向一瞥。

安娜

i Lionnet, Françoise., and Shumei Shi. Minor Transnationalism, Duke University Press, 2005

ii 在美国会话语境中,我提到金在巴黎生活的小区是那里的两个“唐人街”之一。尽管传统上在法语中“唐人街”并没有一个专有名称,而是采用了文字描述:《les quartiers chinois》或 《les quartiers asiatiques》。一场发起重新命名巴黎唐人街的运动正在进行中。从我自己有幸身在洛杉矶的观点来看,我不确定应将这场运动是看作离散唐人街文化的自我肯定行动,还是应将其视为仕绅化的一种手段。也许两者兼而有之。

iii Moten, Fred. Black and Blur, Duke University Press, 2017