The shot of a red light dangling in the art forger’s SoHo studio, the first indelible image of Wim Wenders’ 1977 neo-noir The American Friend, announces the appearance of a series of conspicuously red things: the red of the professional grifter’s sateen bedding, the thin red column separating the ordinary man from the criminal operative, the lingering shots of red seating of the Paris Metro after the first successful assassination, and, finally, the red Volkswagen, the getaway car, careening toward the highway’s embankment as its driver succumbs to his blood disorder. This red – primary red, Coke bottle red – marks moments of stylistic disruption within an otherwise naturalized unfolding of events. The late theorist Jean Louis Shefer called red arbitrary, “without reference to or legitimation in the natural: red things don’t exist.” Red things intrude on the image, articulating through artifice the surreality of the situation; the frame is red.

With The American Friend, an adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s 1974 thriller Ripley’s Game, Wenders anticipated the stylistic turn auteurist cinema in Europe would take over the course of the following decade, resulting in cinéma du look, although resonant with aestheticism of the period more broadly. (Leos Carax’s Mauvais Sang and Pedro Almodóvar’s Matador, both 1986, for instance, each take up Wenders’ thematic red). Yet, in shifting the action of the novel from Fontainebleau to Hamburg, and the site of conflict from class to culture, Wenders does more with his source material than usher in a new era of aesthetic possibility: he constructs an elaborate treatise on the exchange between Hollywood and auteurist European cinema, one that masquerades as an inverted Jamesian narrative of corruption. The premise in which the con artist Tom Ripley, in this iteration an American dealer of forged artworks living in Hamburg, covertly enlists a local picture framer to carry out hits for an illicit porn ring, locates its metaphor in the introduction of New Hollywood filmmaking techniques and tropes to the gentler realism of 1970s cinema in Europe. The appearance of Nicholas Ray and Samuel Fuller, as an art forger and mob boss, respectively, confirms the metanarrative; both directors, refigured by the film as criminals, received more admiration belatedly, from the Cahiers du Cinéma set, than they did stateside at the height of their careers. Centrally, the charming, nouveau-riche chameleon of Highsmith’s novel is substituted for a tonally discordant, urban cowboy played by Dennis Hopper, flown in from SoHo, yet also New Hollywood. (Highsmith hated Hopper’s Ripley before she loved him.) But if this displaced Ripley now stands in somewhat cynically for the global art dealer (Ripley’s answer to the question of his occupation – “I make money and I travel a lot.” – certainly rings with familiarity), it’s his mark, the framer Jonathan Zimmerman, the creative class precariat, who receives the more nuanced depiction. Whereas Ripley ensnares the novel’s framer owing to a social slight, his reason in the film stems more from Zimmerman’s visual acumen – the art worker’s ability to spot a fake at auction – coupled by a healthy skepticism of the market, a naive desire to stay above the fray. “I don’t like people who buy paintings as an investment,” Zimmerman demurs halfway through the film, too late. Framing, which is to say recontextualizing, extant material, navigating a nebulously-defined international trade, and questioning one’s own agency within that system: could there be a better analogue for the artist working today?

So, The American Friend, the inaugural exhibition at Downs & Ross’ new location in SoHo, proceeds from an insider’s joke connecting the complex power dynamics of the film to the New York art market’s enduring import of artists based in Germany, starting perhaps with those centered around Cologne in the 1990s, or, more pointedly, to the emergence of Berlin’s American expat scene in the 2010s, of which several of the exhibiting practices belonged. Yet in presenting works by these artists in particular, by Darja Bajagić, Gretchen Bender, Eliza Douglas, Nina Hartmann, Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff, Dani Leder, Kate Mosher Hall, Rute Merk, and Heji Shin, the exhibition simultaneously surveys modes of artistic production within a global image economy that has paradoxically supplanted and expanded the role of the contemporary artist.

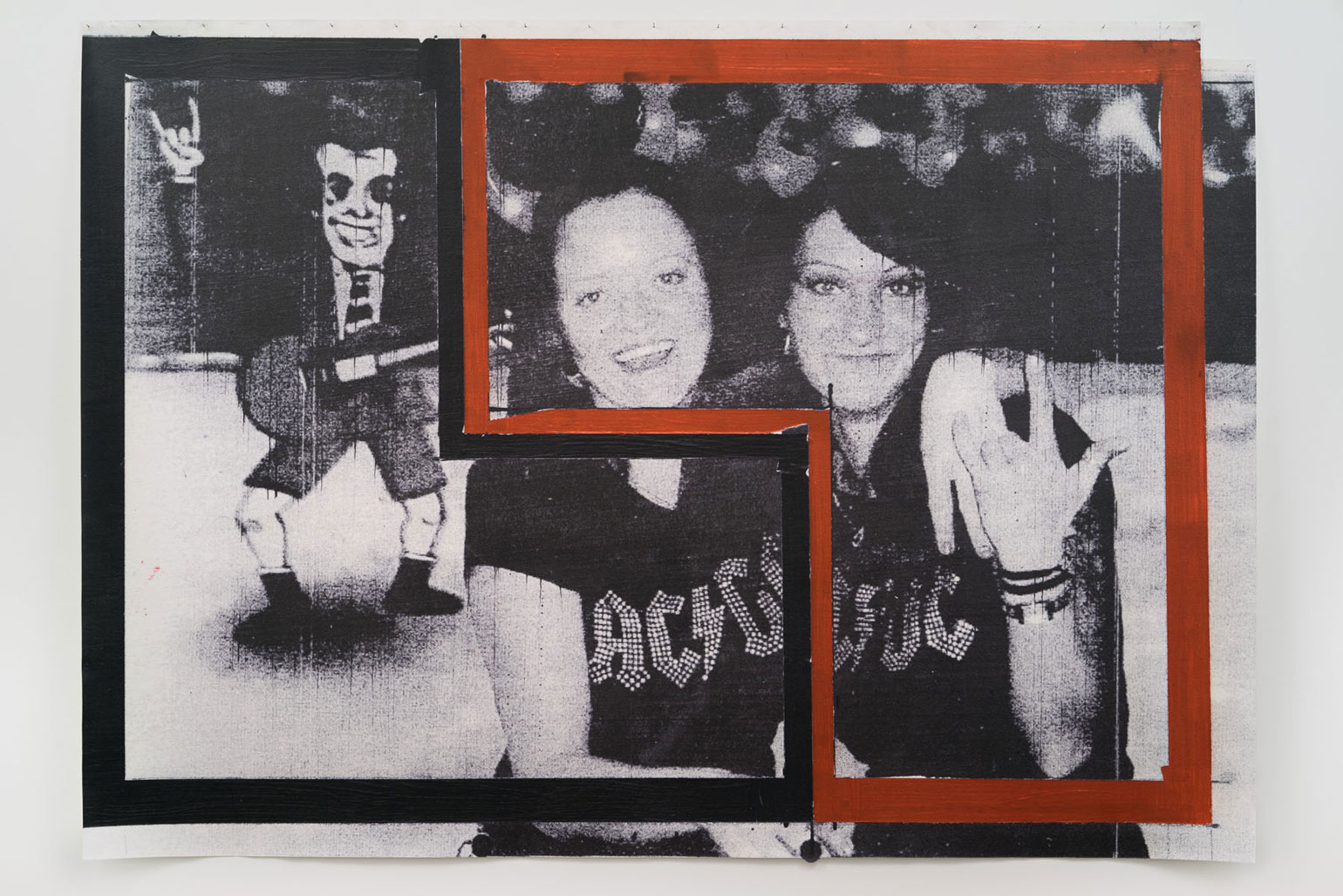

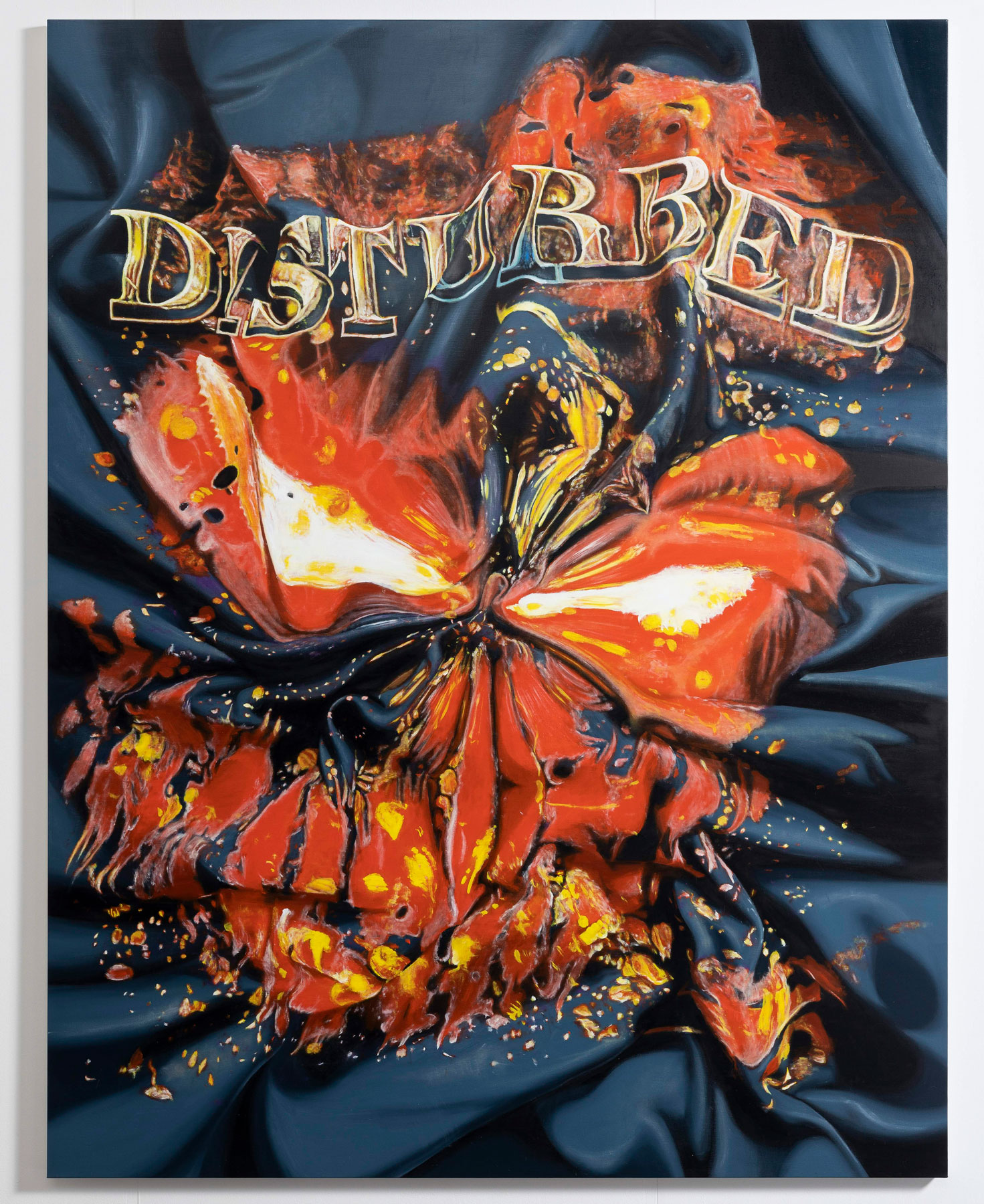

Delineating the initial shift in the 1987 essay “From Work to Frame,” the late critic Craig Owens borrows a phrase once used by Robert Smithson to define the frame, the subject of much work contemporaneous to him – “the apparatus the artist is threaded through.” As with the plot of a Highsmith thriller, with its singular emphasis on character, the apparatus is subject to the contingencies of individual actors, those who eschew conventional modes of authorship and embroil themselves in alternative means of employment. These strategies “shift attention away from the work and its producer and onto its frame – the first, by focusing on the location in which the work of art is encountered; the second by insisting on the social nature of artistic production and reception.” What remains useful from this analysis is Owens’ insistence that this turn reflects a general condition of cultural production, not limited to early projects of institutional critique. Just as well, Owens’ notion of “containment,” with the term’s geopolitical implications intact, returns as a reassertion of authorial control, animating a number of works in the exhibition. Does the institution contain the artwork or does the artwork contain the institution? Darja Bajagić’s works on view, initially produced for a controversially canceled exhibition in 2018, implicate the viewer in strands of political discourse preferably ignored, emergent forms of regressive nationalism that have arisen, although often left unsaid, from both local and global economic crises. the stony-faced nymphomaniac powerfreak, projecting an aura of normality with Susann, 2018, is exemplary in its address of these issues, drawing associations to both the Western canon and far-right nationalist organizations like the Golden Dawn, reminding us that the frame is neither neutral nor benevolent. These works contain that frame.

The pleasure of reading certain texts by Owens’ contemporaries – Douglas Crimp’s “Pictures,” for instance, or Barbara Kruger’s late 1980s television column for Artforum, or George WS Trow’s book-length essay “Within the Context of No Context” today, derives, at least in part, from the quaintness of the collective analysis, the failure to foretell things to come. Entropy produces a certain nostalgia for a period in which the term “media apparatus” simply stood in for an appliance, referred to television. Through time, subtle distinctions dissolve and demand renewed interrogation. Flash Art, 1987, one of two works on view by the late artist Gretchen Bender, centers a single-channel video screen into a compositional matrix of appropriated imagery, surrounding its hour-long video stream – contemporaneous music videos by Dolly Parton, Janet Jackson, among others – with reproductions of works by the painter David Salle, the art star of the moment. The red frame returns bearing a question: Are we having fun yet?

Diverging from the appropriative strategies of closely associated artists like Kruger and Sherrie Levine, Bender borrowed from sources already medial, already in mass circulation through reproduction – images produced by products: the market artist, the pop singer, the news anchor. It is not the contrast of high and low that animates Flash Art, but a recognition of the annexed images’ inherent sameness. “To think of Bender’s work in this way as a new union of ‘fragments’ is to misunderstand what she is describing – the potential technological reduction of all images to a single digital code,” Jonathan Crary wrote earlier, in a 1984 issue of Art in America. “The role she assumes is not one who makes, quotes, or binds together images, but one who regulates flows and channels currents on a homogenous surface of pure data.”

Within the context of an exhibition rife with appropriative gestures, it feels apt to keep the realization of Crary’s premonition in mind. Acting as a cultural sieve or modem, the contemporary artist produces new images, novel relations, from the depths of pure data. In Kate Mosher Hall’s Take Hold, 2022, for instance, an image of a placeless landscape sets the stage for a play between digital manipulation and material manifestation; the image’s refraction and degradation through silkscreen reproduction takes precedence over the content of the image itself. The circulating image sets the work into optical and referential motion, serving as the catalyst for other concerns.

The outsized role of the United States in cultural production reemerges from these concerns as well, drawing us back to the film from which the exhibition gathers its name. The media theorist Maeve Connolly, in the 2009 study The Place of Artists’ Cinema: Space, Site, and Screen, proposes, through an engagement with the earlier writing of German film historian Thomas Elsaesser, that The American Friend elucidates two differing notions of the United States’ late 20th century influence on Europe: the first “associated with exploitation and imperialism,” the second centering around the US’s perceived “friendship and egalitarianism,” an association nearly upended by the film’s focus on malevolent manifestations of friendship, by “the figures of the double and the vampire.” The latter – the vampire – may be particularly relevant here as a figure of colonization, one in which the victim seeks out the vampire in order to “find in him the image of his own desire.”

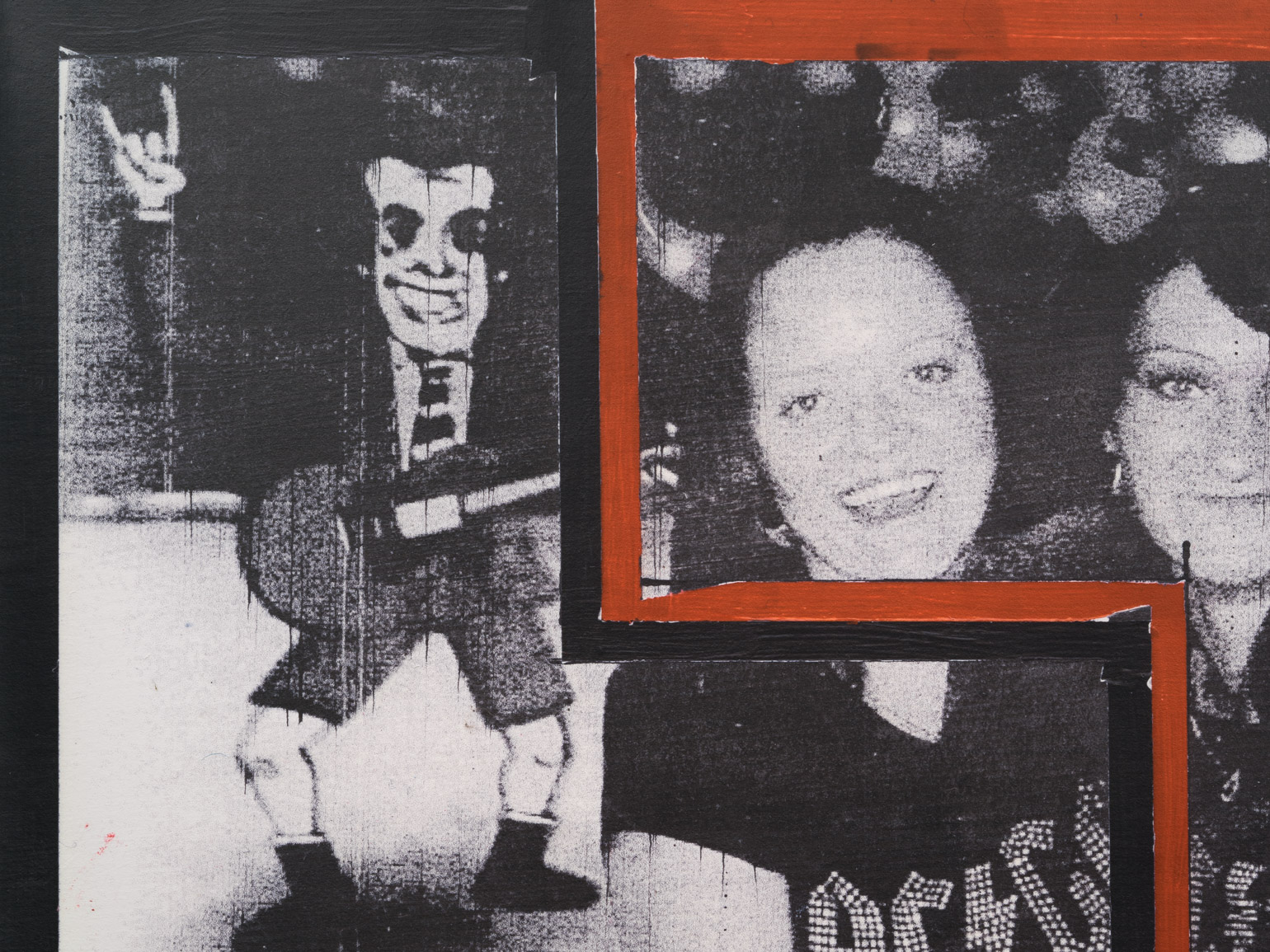

Returning to this throughline, two ambitious works on view complicate the notion of cultural exchange through a series of strategic displacements. The first, Heji Shin’s Operation Phantom Fury, 2020, draws from a series of works in which the artist photographed Ukrainian live-action roleplayers simulating the American war in Iraq. The correspondence between the mediated spectacle of war and its roleplay reenactment is complicated further by the specter of actual conflicts in Ukraine, both in 2014 and again this year. The stark black-and-white of the image draws the scene closer to the film still, incongruously revealing correlations between the conventions of war photography and cinema. Placing herself temporarily in the role of a photojournalist, Shin uncovers a dense network of nodes situated between photographic representation, historical reenactment, and geopolitics, while offering, finally, darker hegemonic possibilities for the arrival of the American friend.

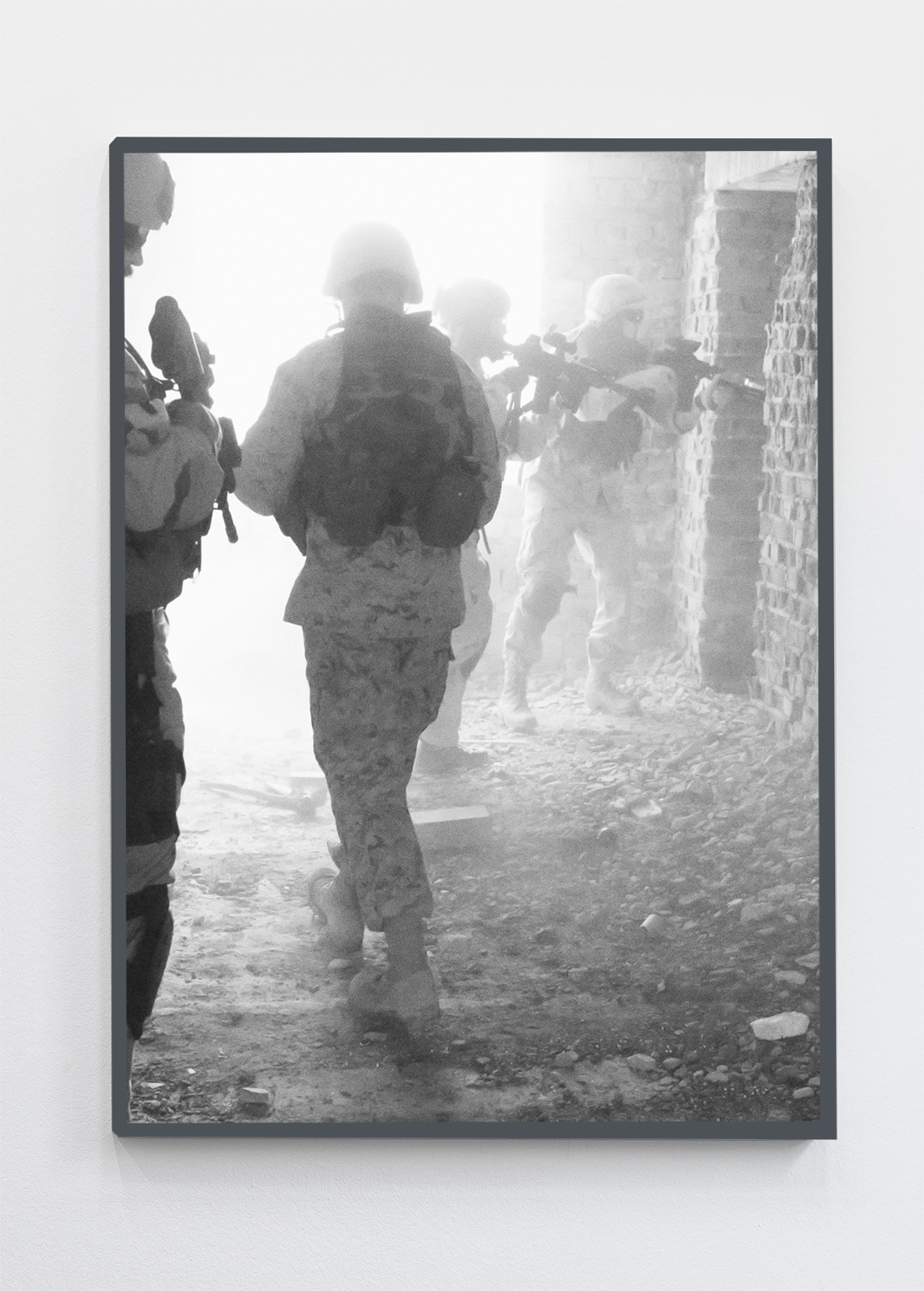

Elsewhere, a restaging of Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff’s installation presented at the 2016 Berlin Biennale, documents the US ambassador’s residence in Berlin-Pariser Platz. Among the relatively austere spaces of the ambassador’s residence – the symmetrically composed living area, the symbolically staged dining room – production lighting and equipment infringe peripherally, effectively refiguring the domestic space as a film or stage set. Deploying previously developed methods of documentation, and utilizing equipment from their performance-based work as New Theater, Henkel and Pitegoff draw this site of diplomacy into their broader project. In doing so, the artists elucidate a correlation between the activities of the US ambassador and their own collaboration as American expats based in Berlin, a relationship between nations that has driven their professional and delicately communal endeavors. Yet the social implications of these photographs are ultimately subsumed by their site-relational installation, which is to say, the work’s frame. While this work, initially installed in a space used as a set for the television show Homeland, once implicated government buildings in its mirrored surface, at the exhibition, the work’s wall of tiled mirrors reflects a changed context: the crowded intersection of Canal and Broadway central to New York’s newly located art world.