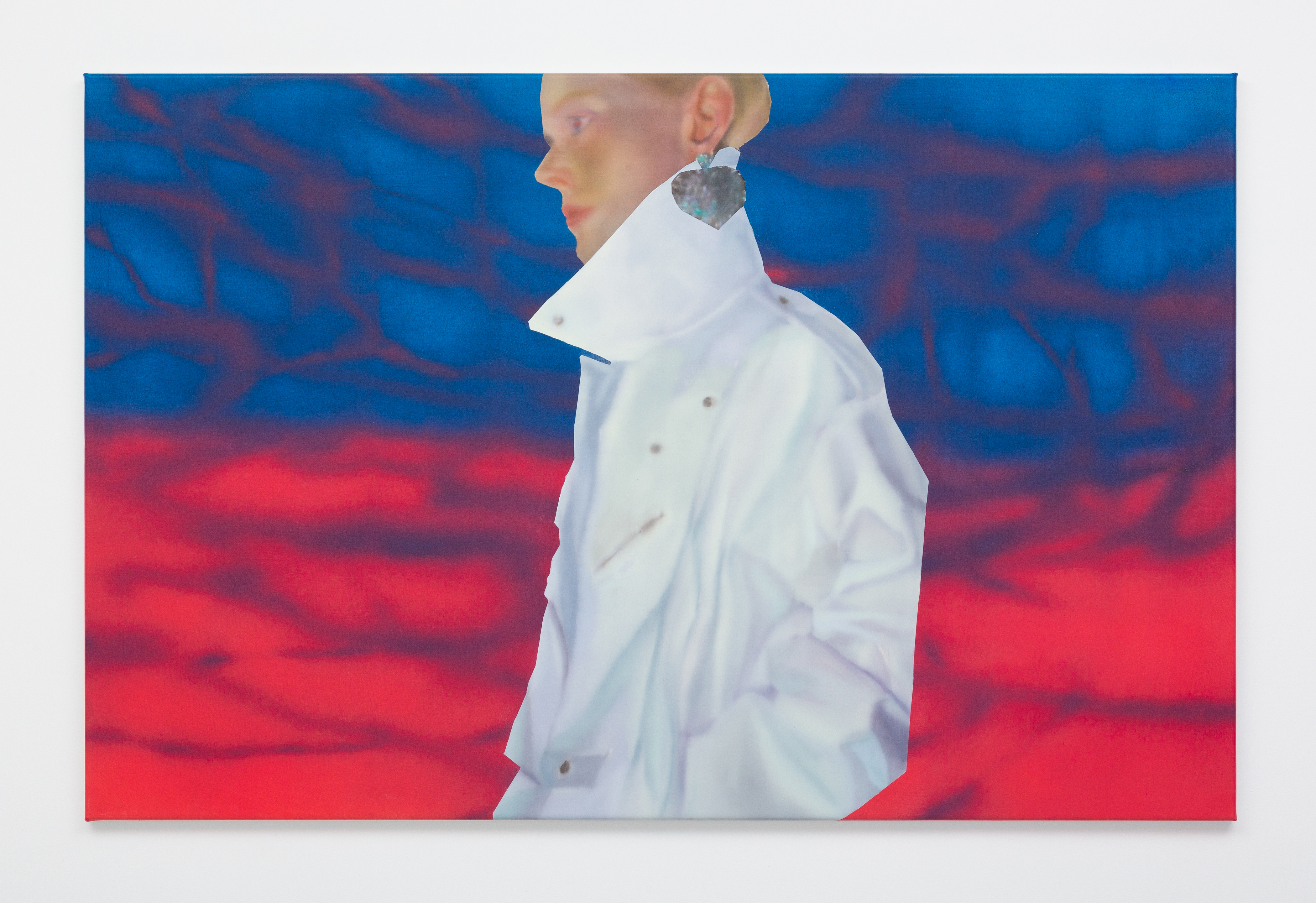

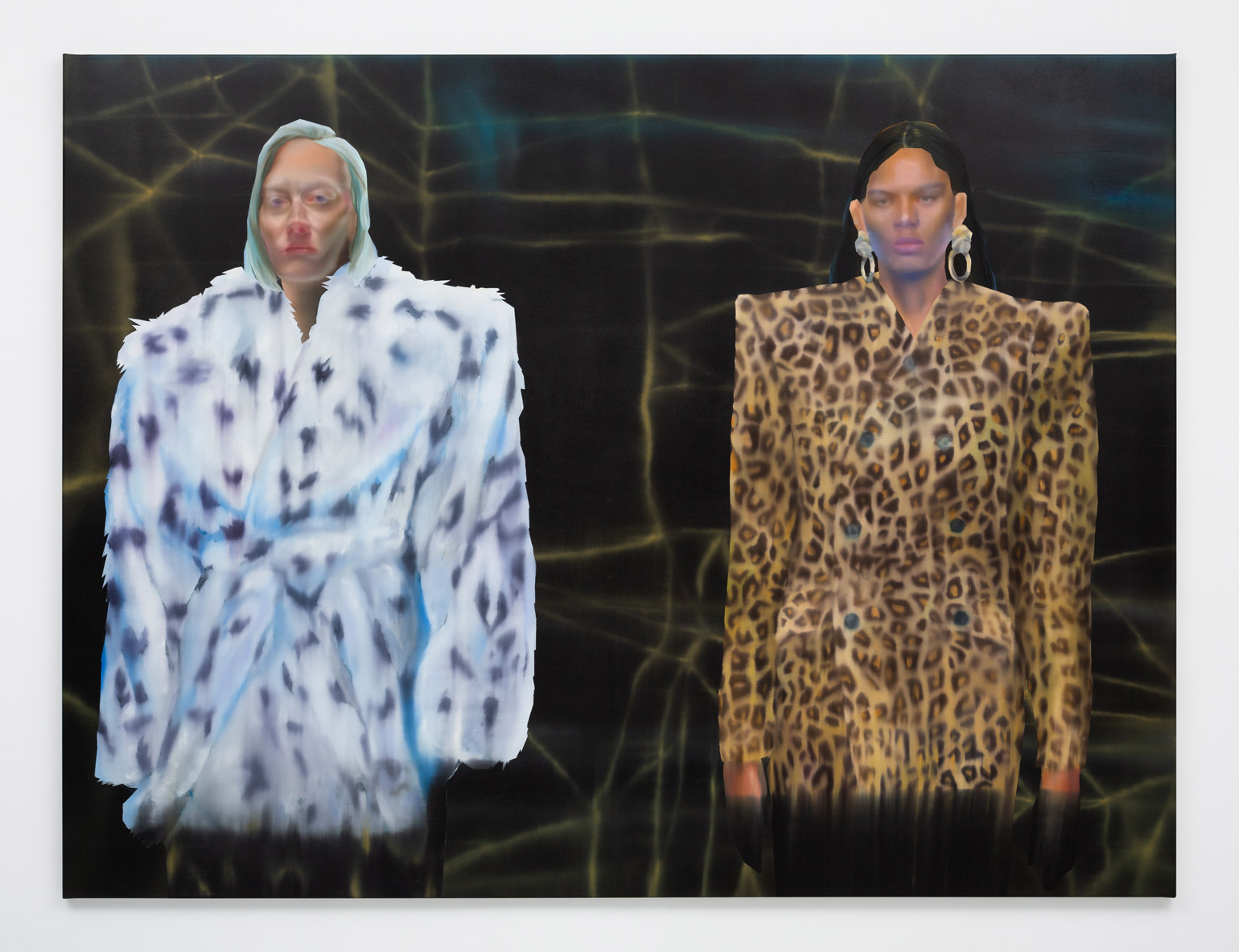

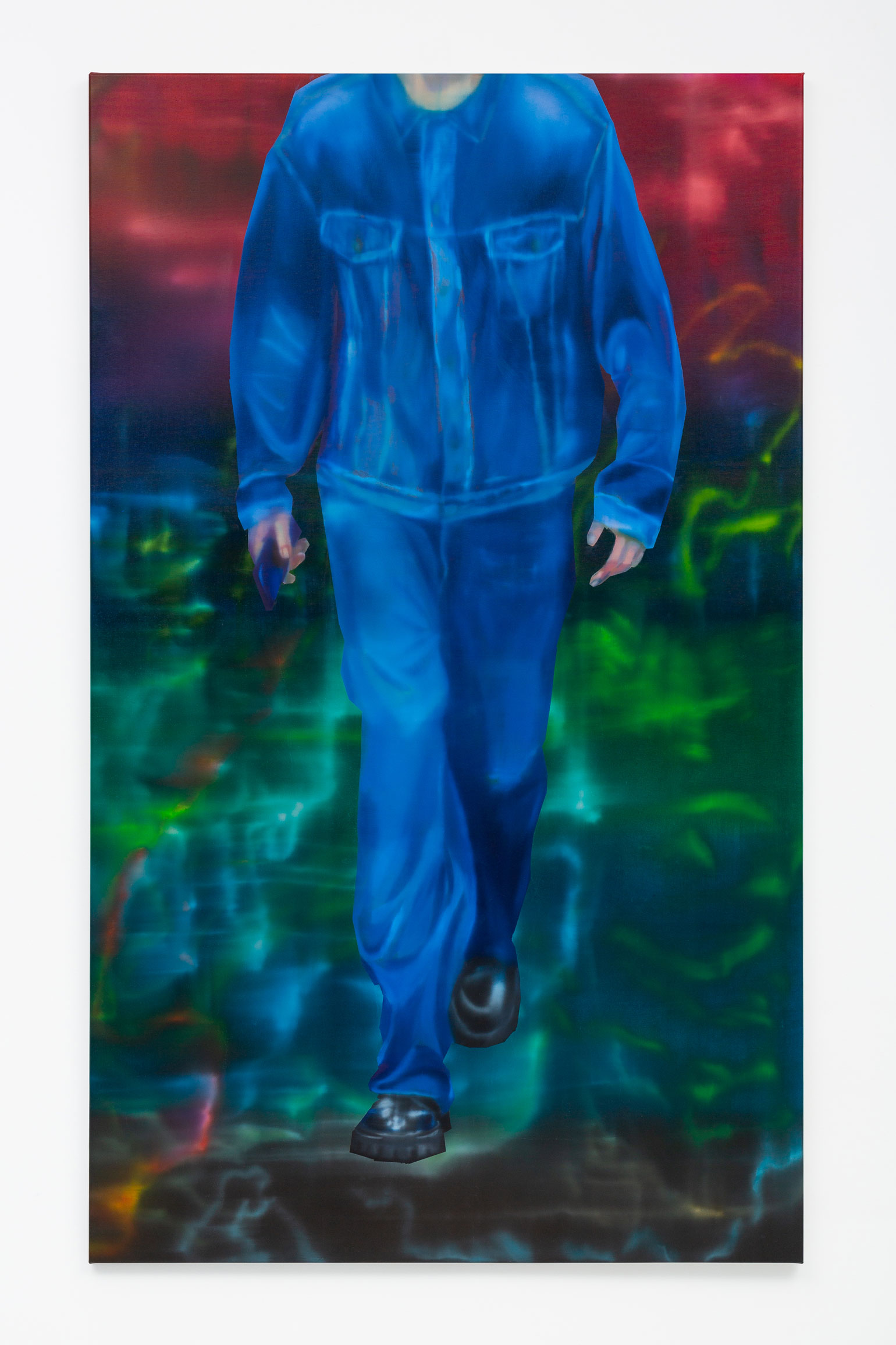

I got up. I went to work in the morning. New York Fashion Week was still being held, but on a smaller scale. Designers sent models down the runway in face masks, gloves, and even scrubs, many branded with designer logos. The accessories industry exploded. The last show of Fashion Week was Marc Jacobs, whose spring collection eschewed obvious references to Shen Fever and aimed for something more subtle. Held at the Lexington Avenue Armory, the show featured the drop-waist, boxy dress silhouettes of 1920s flappers, rendered in muted shades of stone, black, baby blue, the gentlest seafoam. If these were party outfits, they were for the most somber party.

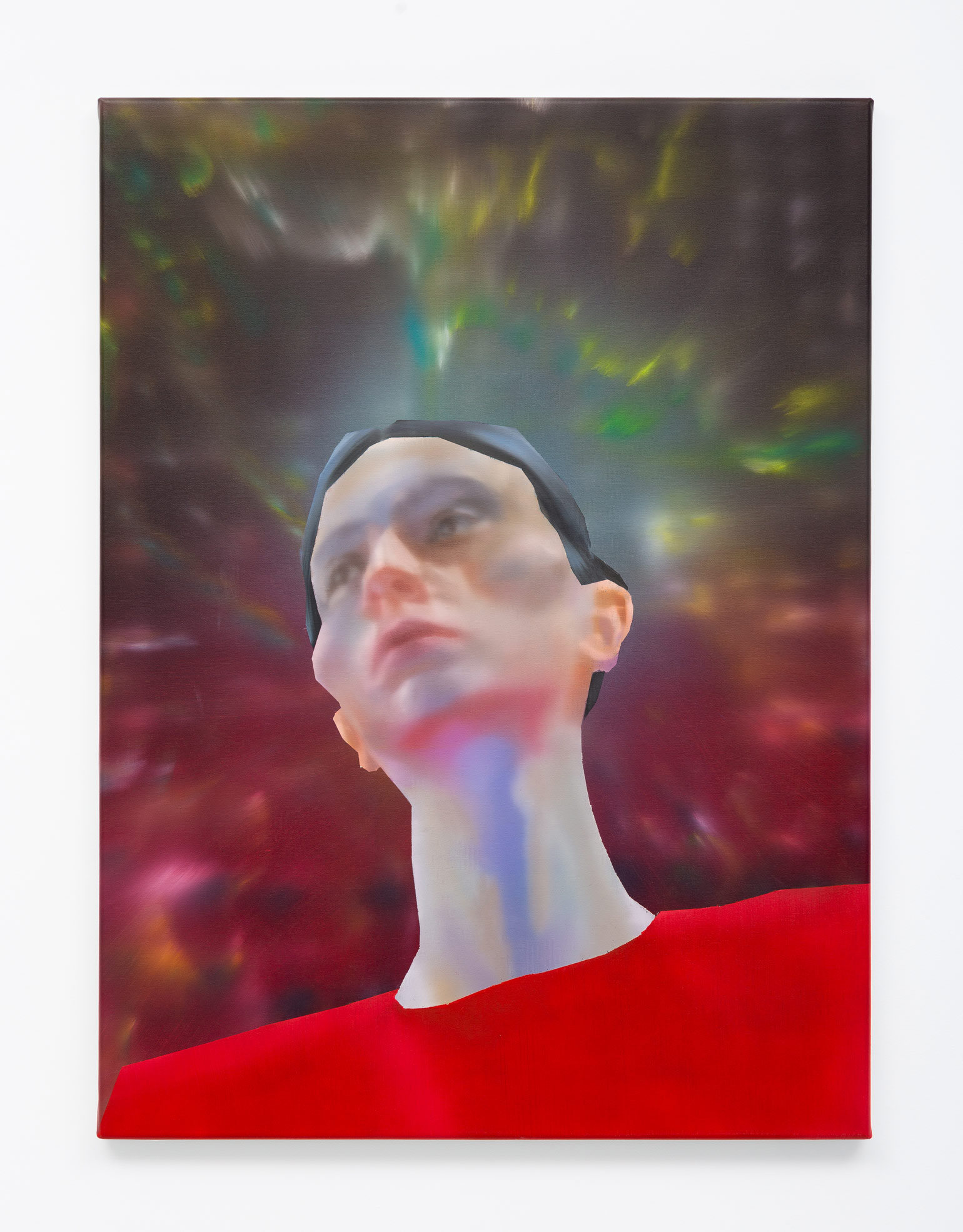

Most noticeably, the clothes incorporated translucent materials, from the cellophane organza of the tiered skirts to the see-through plastic of the boots and pumps, which left parts of the models’ bodies, incongruously, uncomfortably exposed. Reviewers commented on how the transparent features highlighted the way that we had all begun assessing each other’s bodies, in fruitless attempts to detect Shen Fever. Fashion was beside the point. We didn’t look at a woman to appreciate her outfit, we looked at her to evaluate her potential sickness.

At my desk on an especially uneventful afternoon (production jobs placed at Spectra were slowly drying up), I watched a video of a backstage interview. He spoke in his low, characteristic drawl: I didn’t want it to feel real.