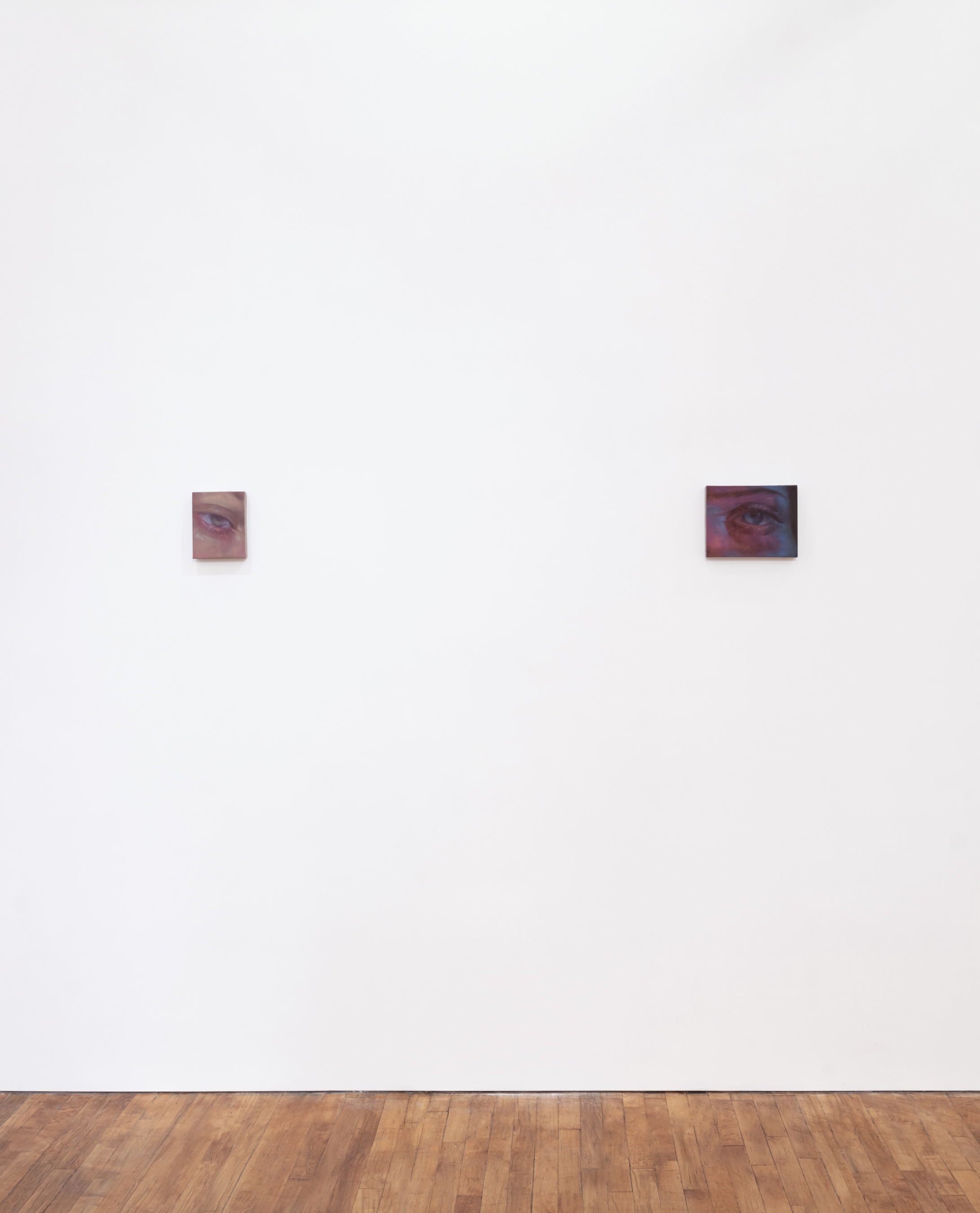

Tara Downs is pleased to present Mute the first solo exhibition by Pei Wang in the United States. In Wang’s intimate paintings, the filmic close-up and the fragment comprise the formal devices through which the artist produces photorealistic representations of the human form, conjures moments of narrative suspense, and constructs elaborate correspondences with the history of painting.

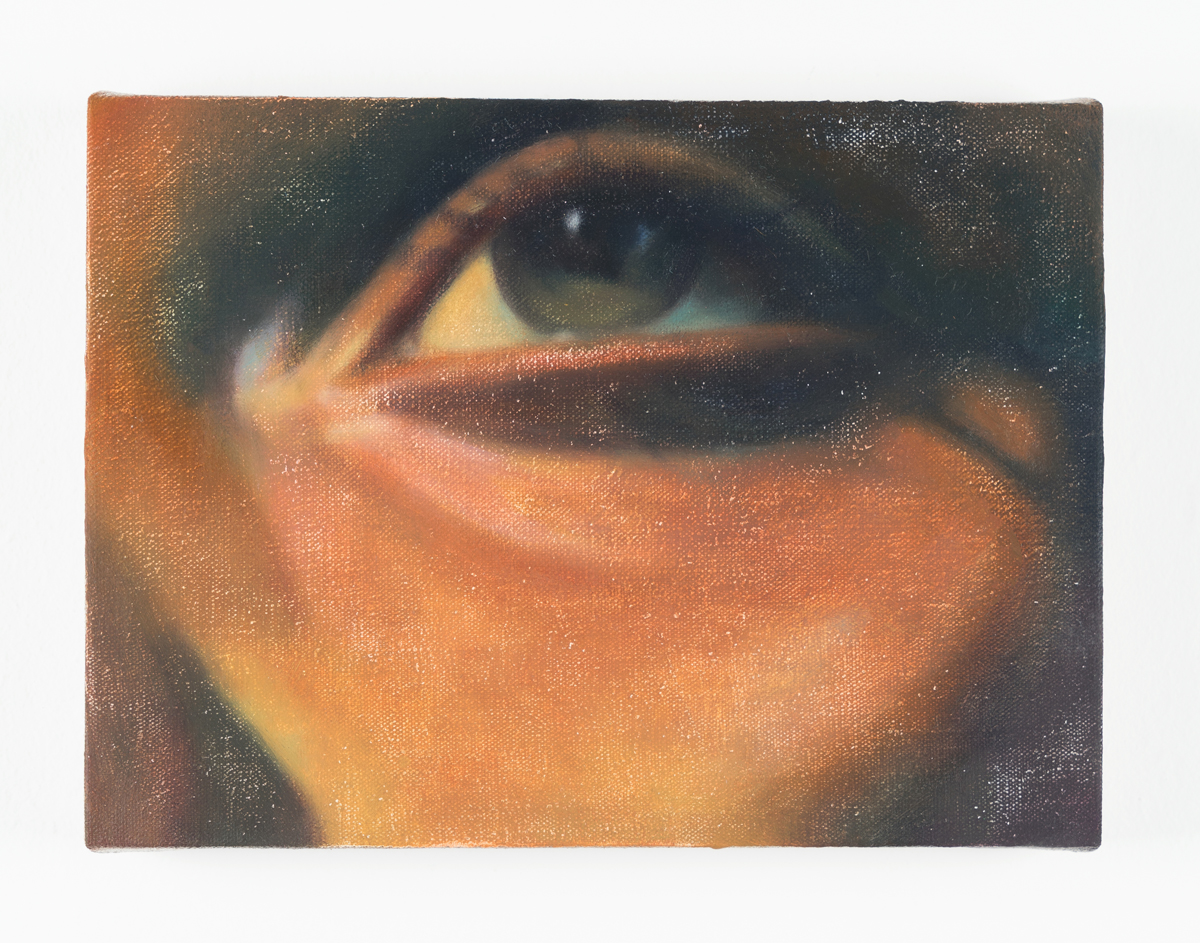

Like the artists of the Beaux Arts system, Wang began his painting practice by copying the Old Masters, and now draws upon more arcane material – film stills, found images, personal cellphone photos – to undergird his staging of contemporary affect. In these paintings, cultural memory and personal history intertwine, not only with one another, but also with techniques and materials drawn from the long tradition of painting. Borrowing a sense of light from the Baroque period or underpainting with casein, a material often used in ancient mural painting, the artist gestures toward a more expansive understanding of temporality than initially suggested. Just as the early modernists turned toward ancient or understudied cultures, rather than the classical, as sources of inspiration, particularly for figuration, Wang, too, takes on the role of the archeologist or anthropologist, collecting documentation of unexpected objects, and layering them upon somewhat unplaceable images culled from media culture.

As a scholar of medieval art, Wang has traveled across the Mediterranean – Greece, Cyprus, Algeria, Egypt – to inform his research, and this research has in turn altered his parallel work as an artist. The collision of disparate cultures, the development of art through its networked distribution, and the sense of hybridity engendered by their objects, are all themes of current medieval studies that resonate with the global character of contemporary art and culture. It makes sense here, too, that Wang looks to the respective studio methodologies of Zao Wou-Ki and Alberto Giacometti, and their cross-cultural friendship, as guide posts for his own activities. While many artists concerned with the global may submit themselves to prescribed understandings of contemporaneity, or succumb to illustrating current trends in critical theory, Wang works more closely in the lineage of these earlier figures, transcending any set notions surrounding cultural specificity through a broader array of study, and granting close attention to less obvious objects of scholarship. Indeed, such works function as compressive feats of aesthetics histories as much as they as operate as beguiling, technically-accomplished oil paintings. In this sense, The Fragment 02, 2023, may be emblematic, combining a sort of surreal take on the post-Impressionist ideal with the distortive, seemingly impossible figurative photography of Edward Weston.

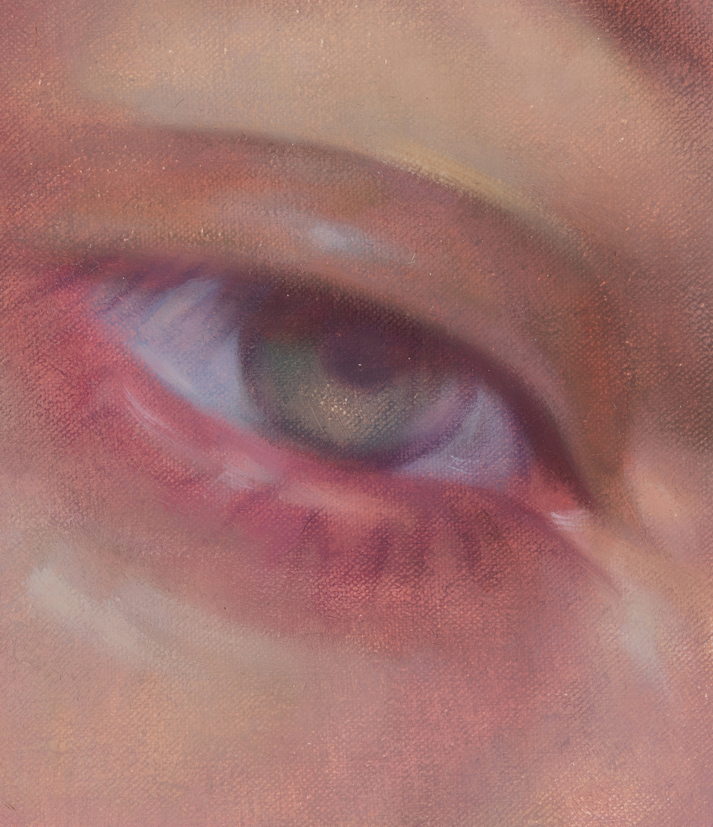

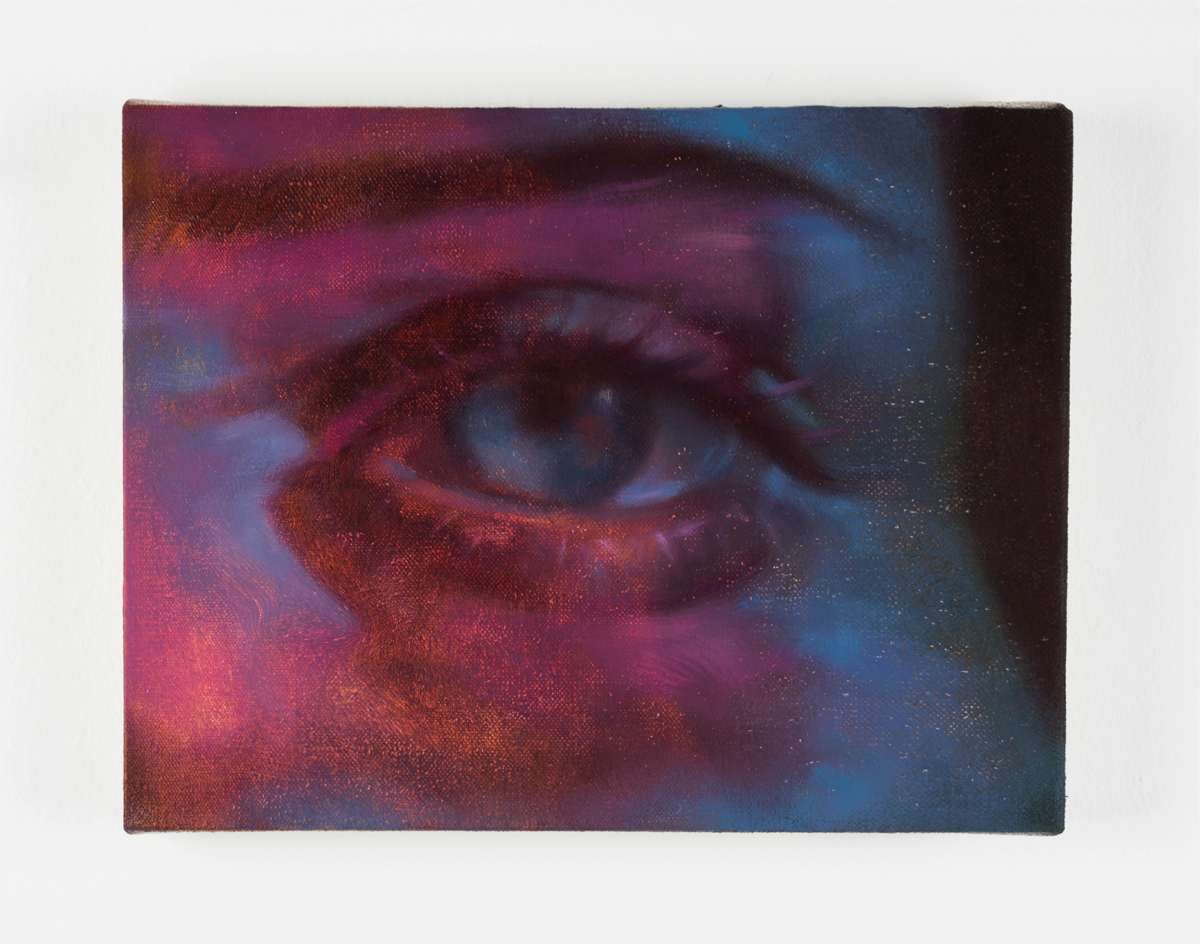

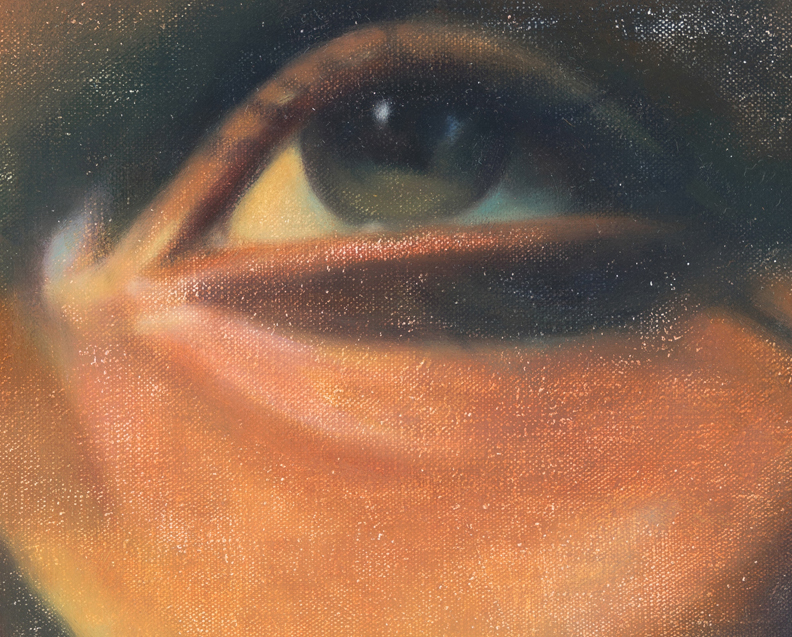

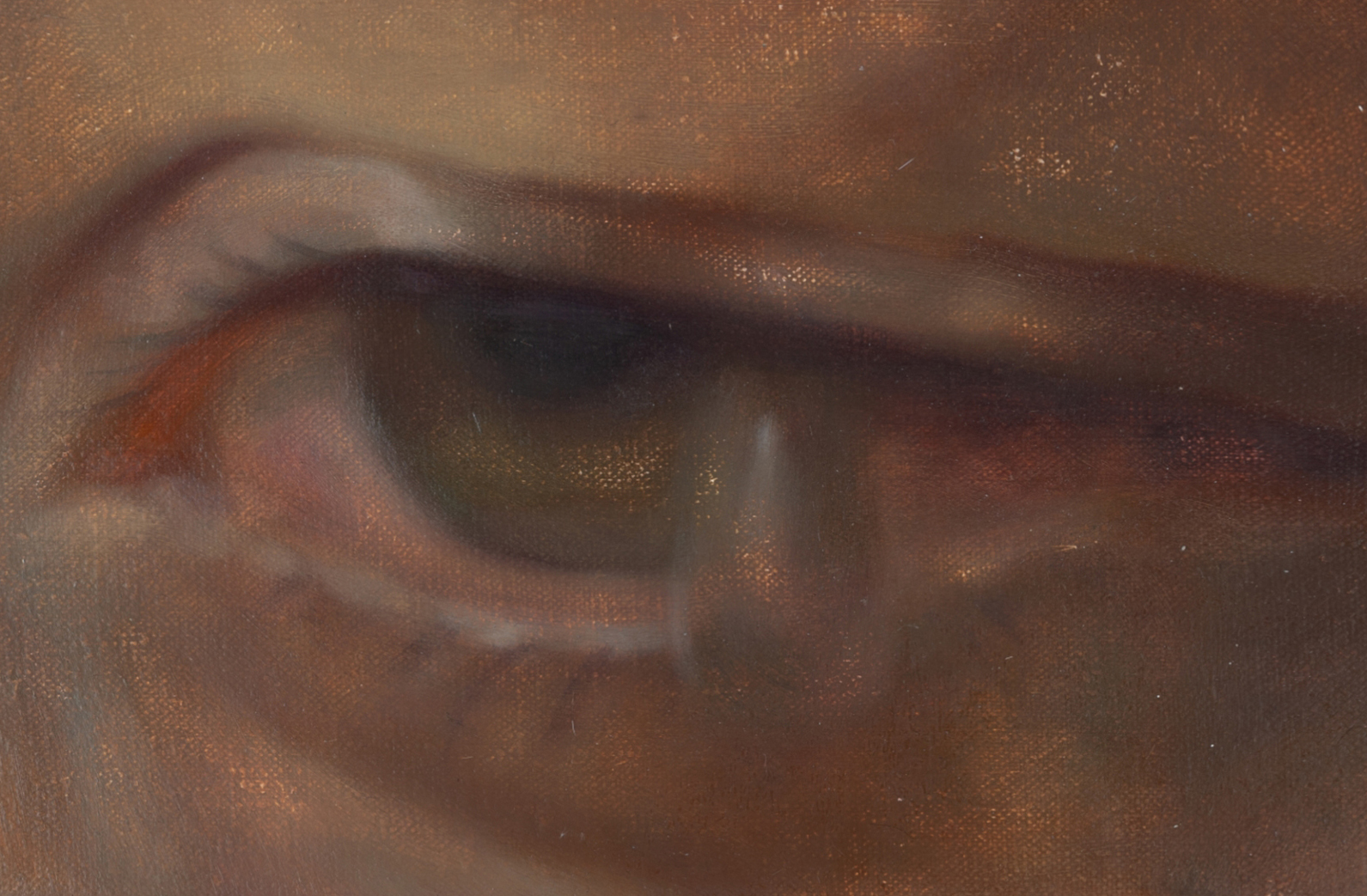

Elsewhere, the recurrent motif of the eye, and its implicit, attendant literature relating to the gaze, brings us back to Wang’s use of photographic source imagery. Against the gleefully oppositional sense of appropriation that has marked the last half-century of artistic production, Wang works in a more subtle register, accurately recognizing culture as a far broader process of accumulation and cross-pollination. One would not immediately assume, for instance, that works such as Mute 30 an oil painting of a figure’s teary eye fastidiously rendered in extreme close-up, were derived from Man Ray’s photographic series of the same subject, Larmes de Verre, 1930–1932. The flat uncanniness of Man Ray’s image is exchanged for a more ambient sense of unease, although the compositional ambiguity, the logic of the fragment, remains. To interpret this act of translation as predominantly a shift in tonality may be to note the unexpected, propulsive contemporaneity of Mute 30 and other oil paintings by Wang much like it. For all their appeals to the past, these paintings ultimately operate in the present-tense, incisively embodying the emotive interiority of the artist today.