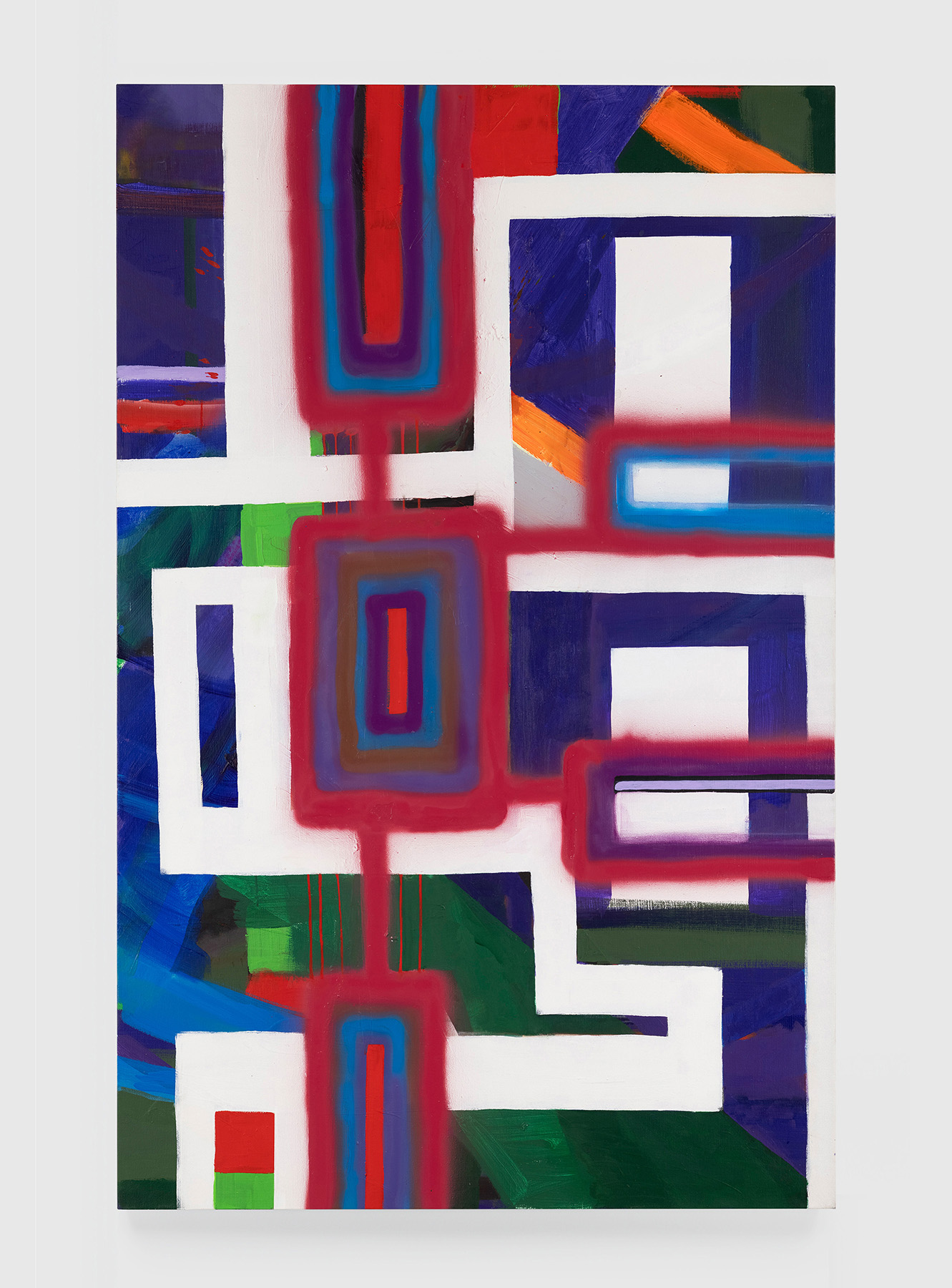

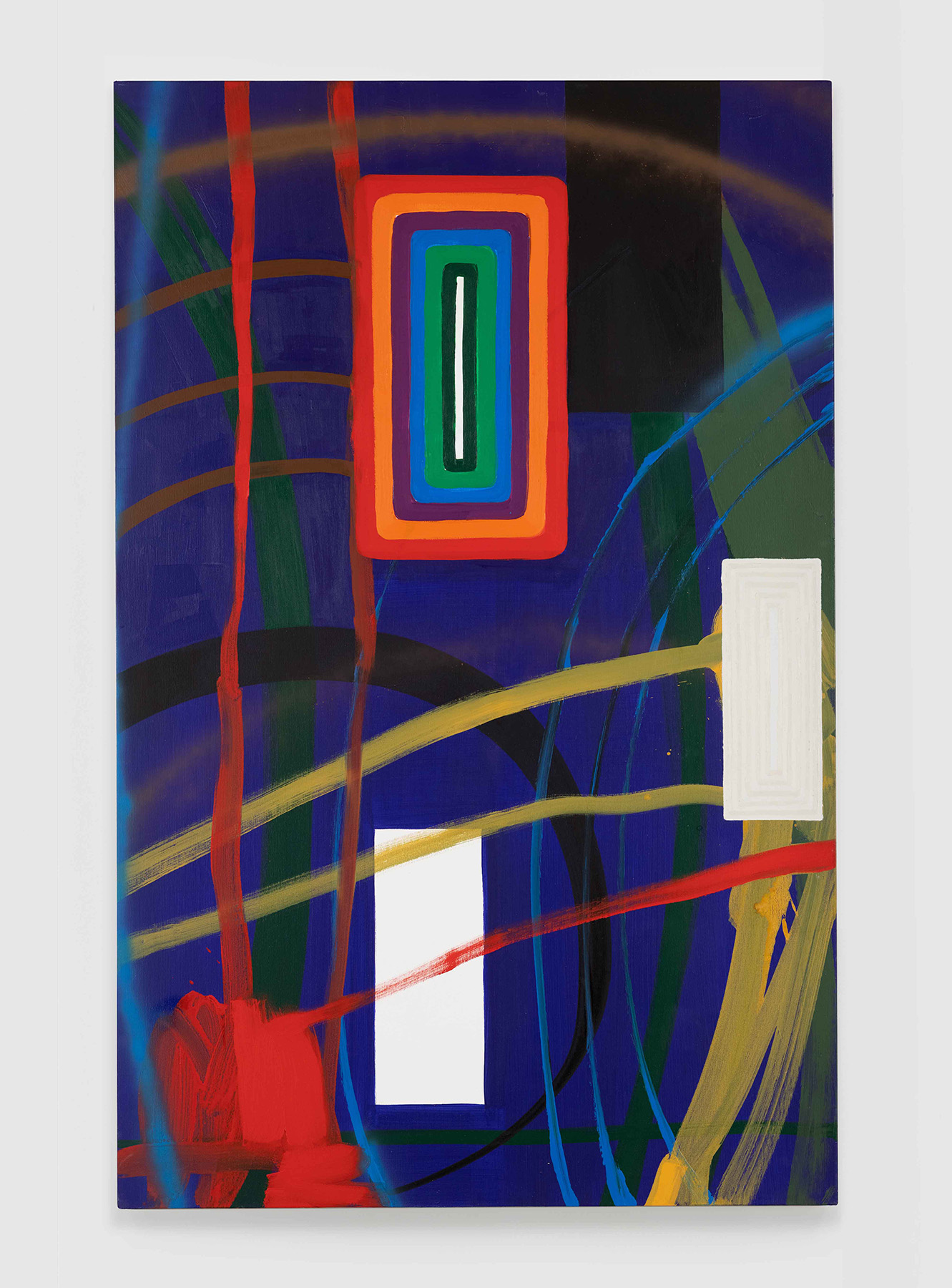

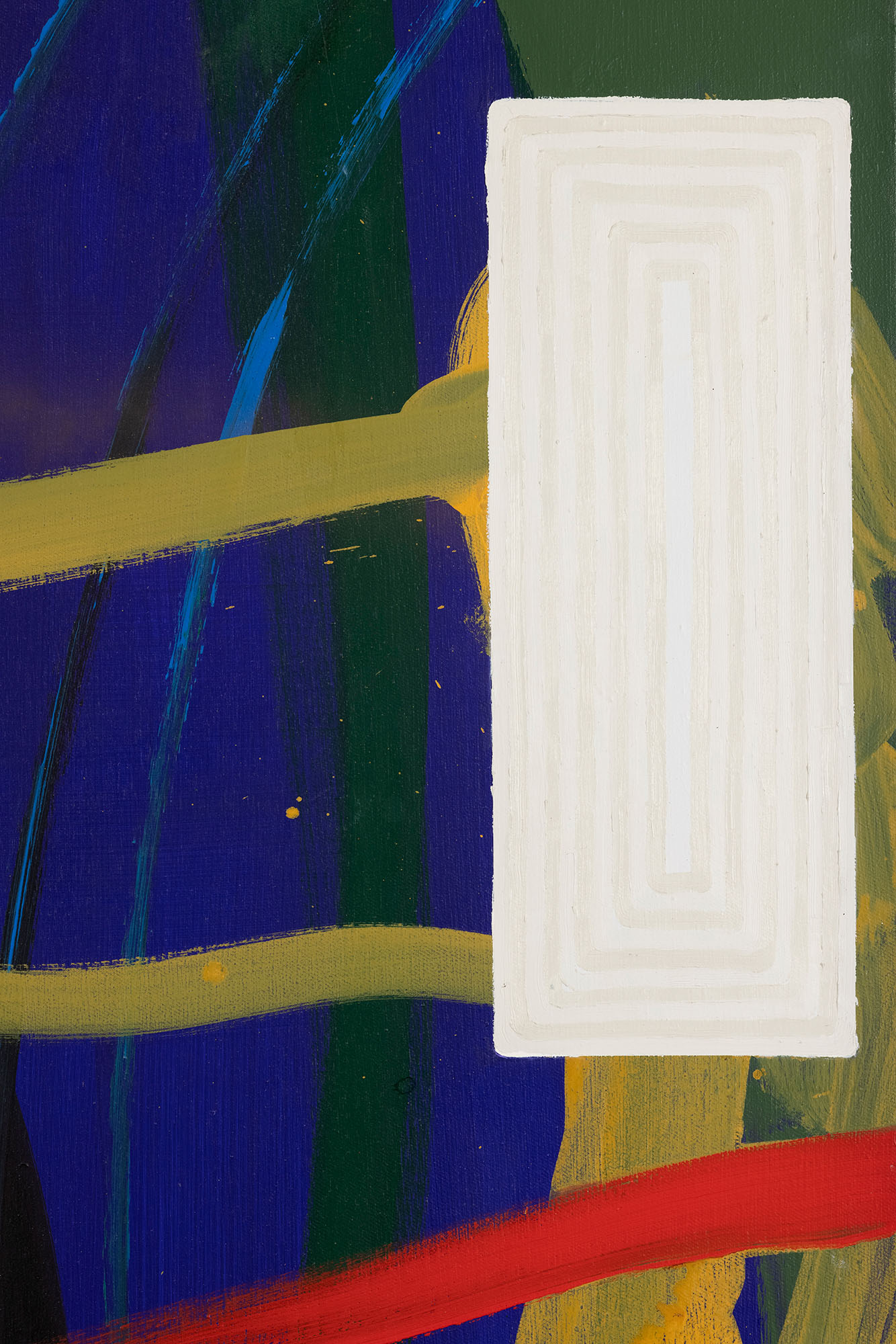

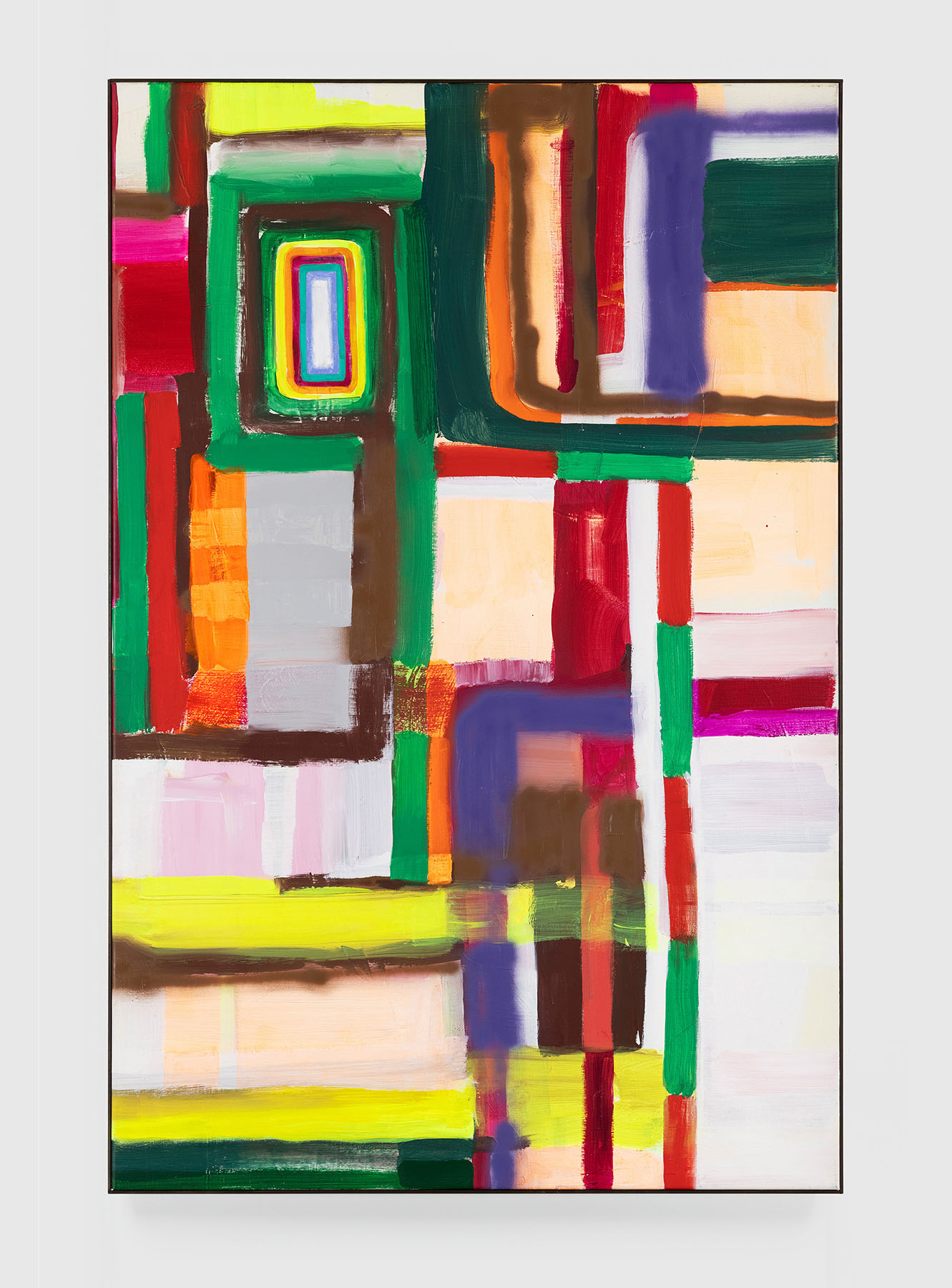

Paths of vibrant color in red, orange, violet, blue, and green wind symmetrically around a centerpoint, forming concentric rectangles that glide in a web of gestural lines. They suck the viewing eye in, “like a snail crawling into its shell and away from man” (Kandinsky). Here one encounters generics of popular painterly, optical “tricks” that have been tried throughout history—in Abstract Expressionism, kinetic Op Art, or simply below the perceptual threshold of the ordinary.

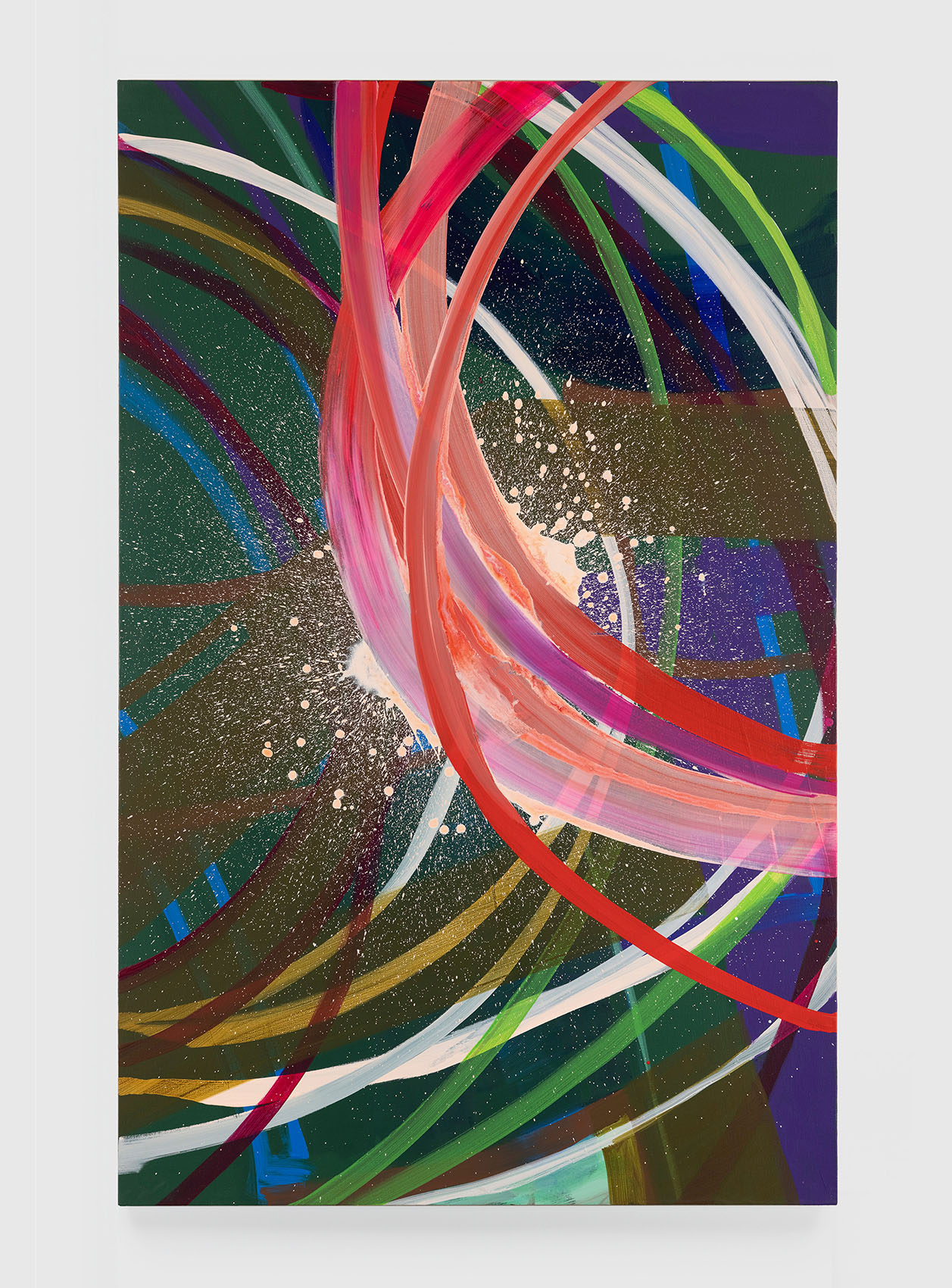

At the beginning of a trick, there is the desire to be deceived, it is said. Klein’s painterly tricks are, in fact, not tricks intended to mislead; on the contrary, what is at stake here is de-ideologized stimulation, indeed, the sharpening of one’s vision and senses. Here it may happen that a patterned line in yellow and black, akin to caution tape, populates the picture plane in defiance of any “golden rules” of composition. The shape appears to be in movement, meandering like Nokia’s coded serpent in the 2005 cell phone game Snake. In the absence of sophisticated renderings, this game employed a simple figure-ground “trick:” Steering the serpent at right angles through a limitless “habitat” while attempting to not run into—or rather be devoured by—its own elongated body. Here, “vital forms” make up self-organizing systems that not only “feed on order” but also have “disruptions on the menu” (Heinz von Foerster) until they move into the next habitat, the next canvas. The same applies to the colored lines that the artist sprayed from above onto canvases lying on the floor (all of Klein’s works are predominantly painted flat on the floor)—the move from floor to wall creates a constant shift in perspective between “top” and “bottom.”

These potent territorial markings in bulky, pipe-like, or filigreed lines let caprice and lawlessness rule over the edges of the pictorial space: they are veritable system wanderers (if not subverters). From time to time, it even seems as if colored lines would cross over from the canvas into public space, vandalize it with bright warning colors, and finally almost threateningly burst into a higher universe. The repetitive ecstasy of blasted pipelines, exploding fleshy myofibrils spurting milky bodily juice or sparking glaringly white fields of color, and the size of the painting—slightly bigger than the artist’s own body—culminate in sheer omnipotence. And still, this hint of megalomania comes across with a wink but “zero cynical, zero ironic” (Klein)—rather, it doubts universal dictums, the view from above: how do we actually represent worlds?

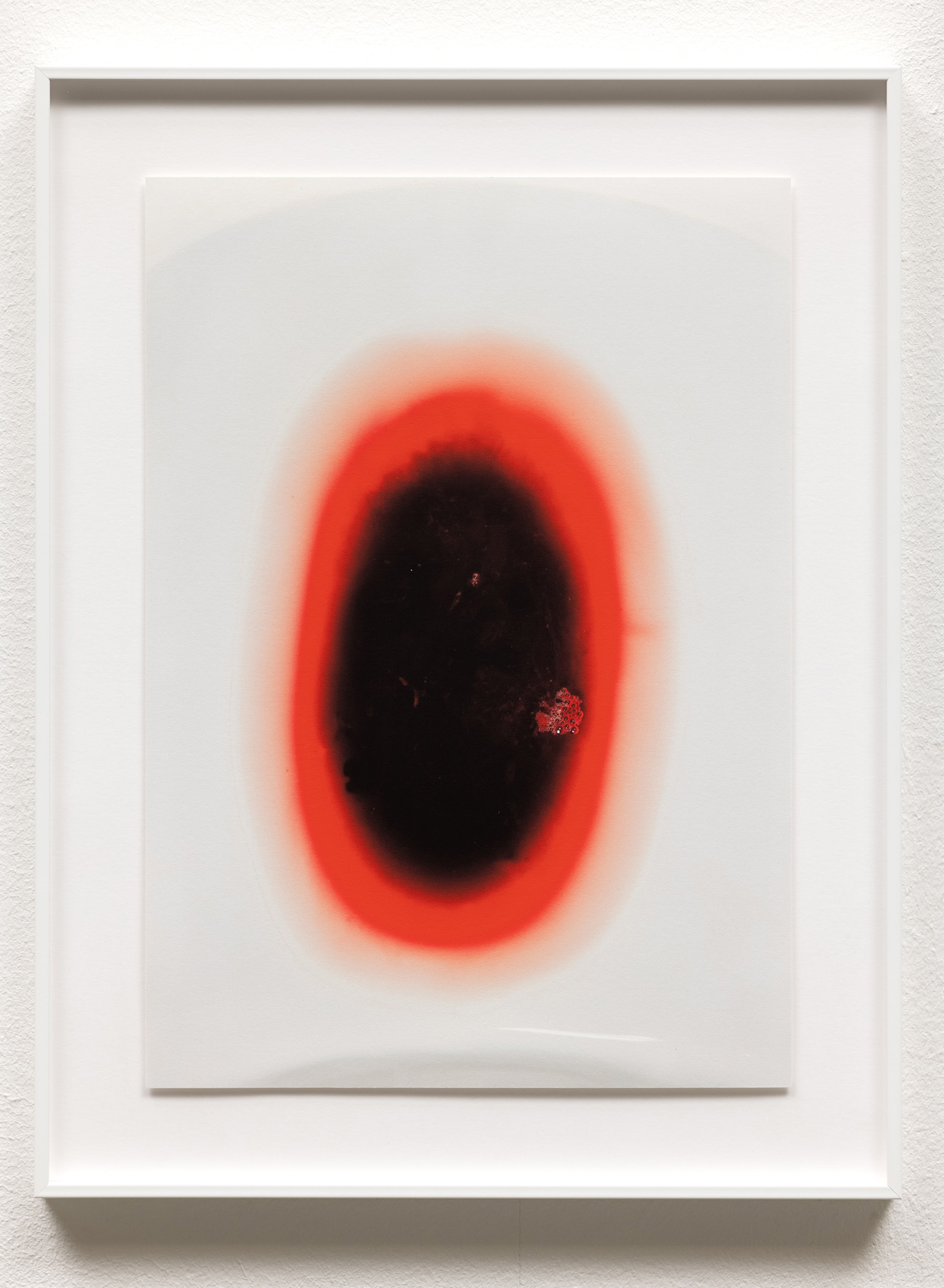

The paintings in the exhibition do not trick: they “situate knowledge” and debunk the “god trick” (Donna Haraway). Such a trick is always performed when knowledge presents itself as detached from the world in which it is integrated, when it denies its own situatedness and thus blocks the joining of partial views into a collective subjective position: namely, one that generates other visibilities, other forms of becoming perceivable and thinkable. This is the case in a framed photograph of a concentric oval circle. From outside to inside, its orbits blend from white into salmon and radiant red centering around an ever-expanding black hole—like an iris opening up a pupil to let in more light. Another look at the photograph reveals a bird’s eye view into a pool of blood with tiny bubbles in a white ceramic toilet bowl. Such a partial view must remain visible.