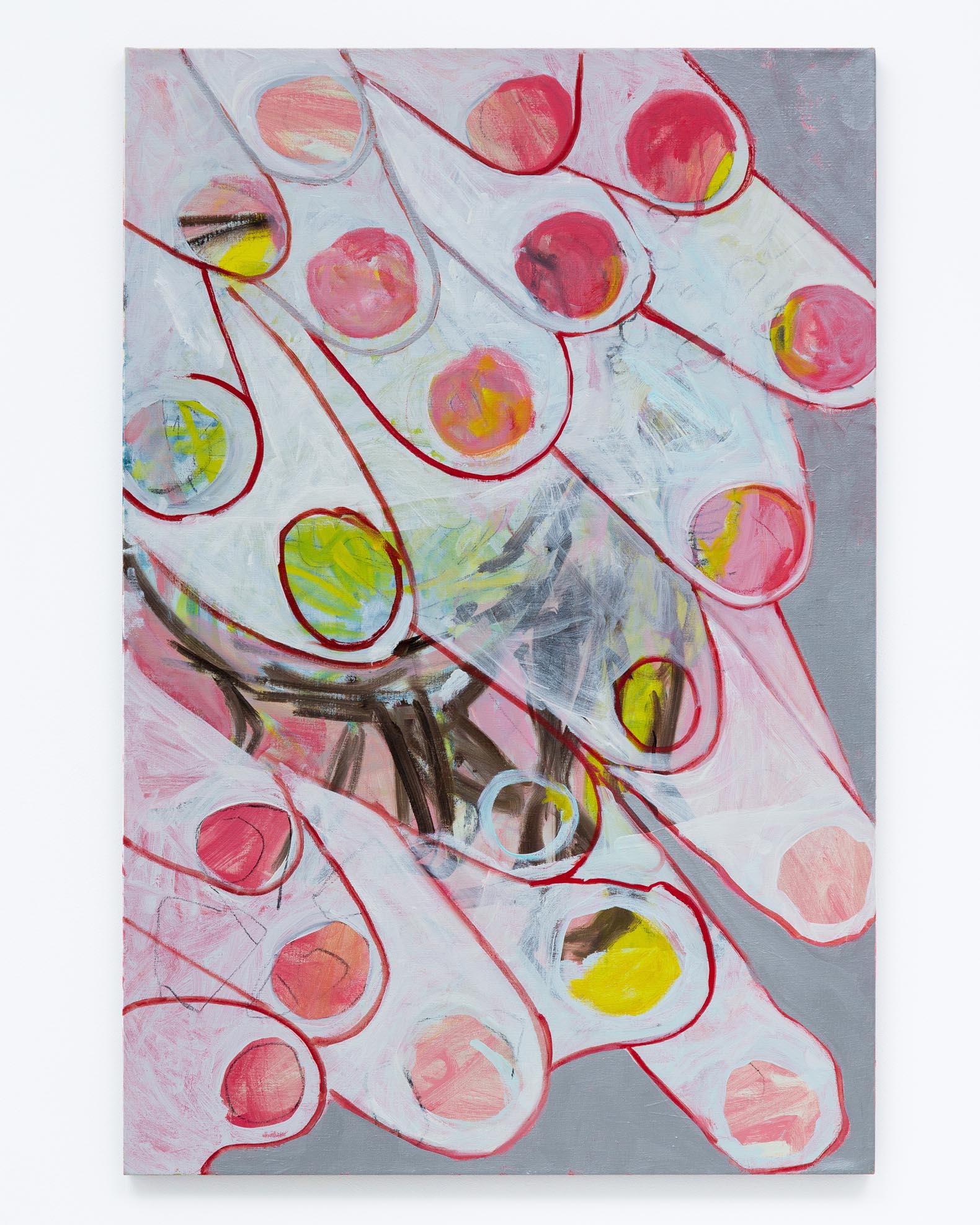

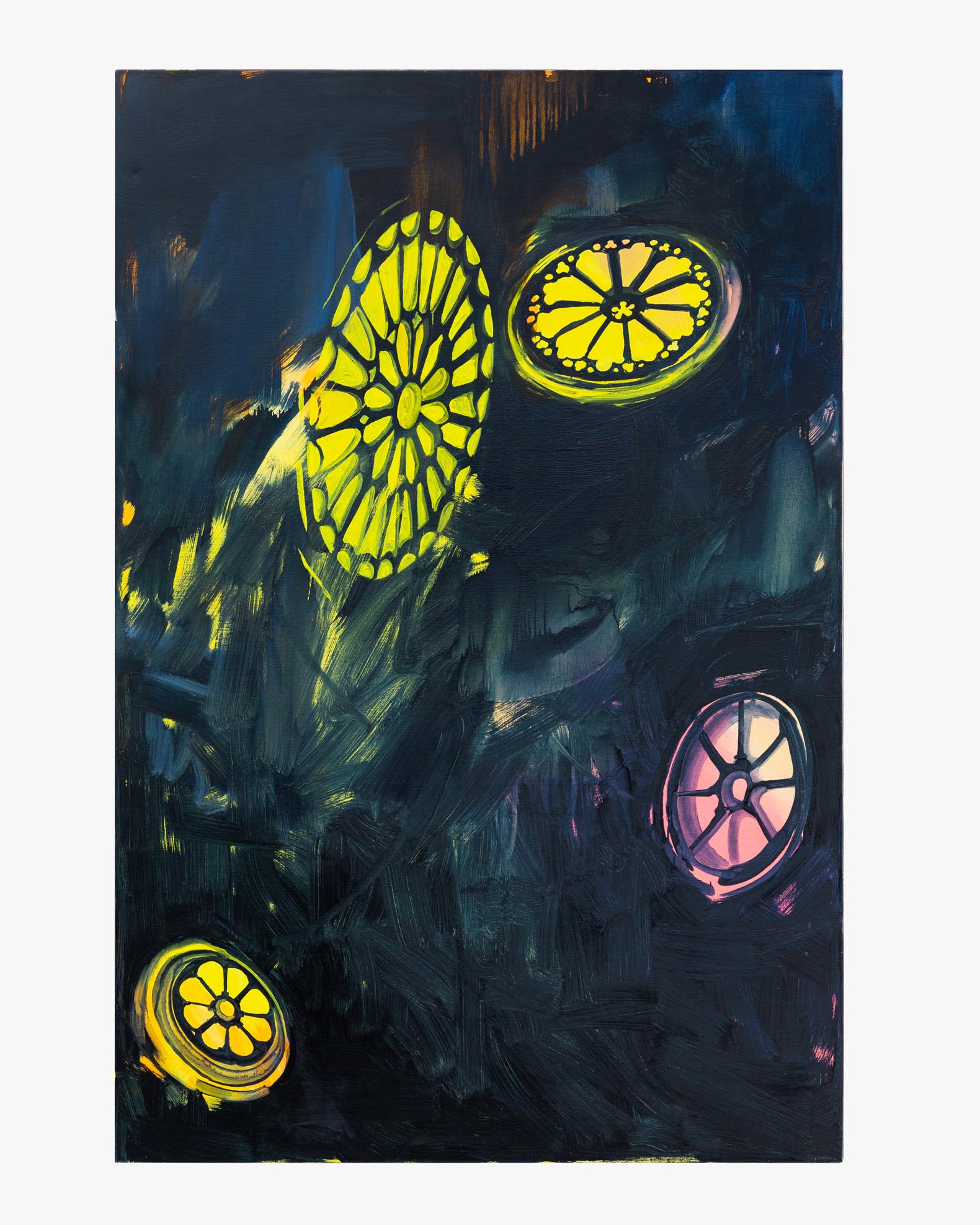

Susanna is a study in anachronisms. Ecclesiastical images from the early Renaissance, inflected through Modernism, are reoriented in the paintings. A disorienting velvety darkness is punctuated by neon rosettes with figures from apocryphal parables scratched into the surface. Seen as interiors, the pictures register as a deeply distorted spaces where rosette windows look out (or down, or sideways) into Prussian blue, organic coffee brown, fluorescent orange, and Diox purple atmospheres. The techniques and elements represent distinct moments in an architectural narrative. The scattered spatial arrangements are oblique, evoking a feeling of suspension. They punctuate the white, transparent, and orthogonal world of the Modulightor building.

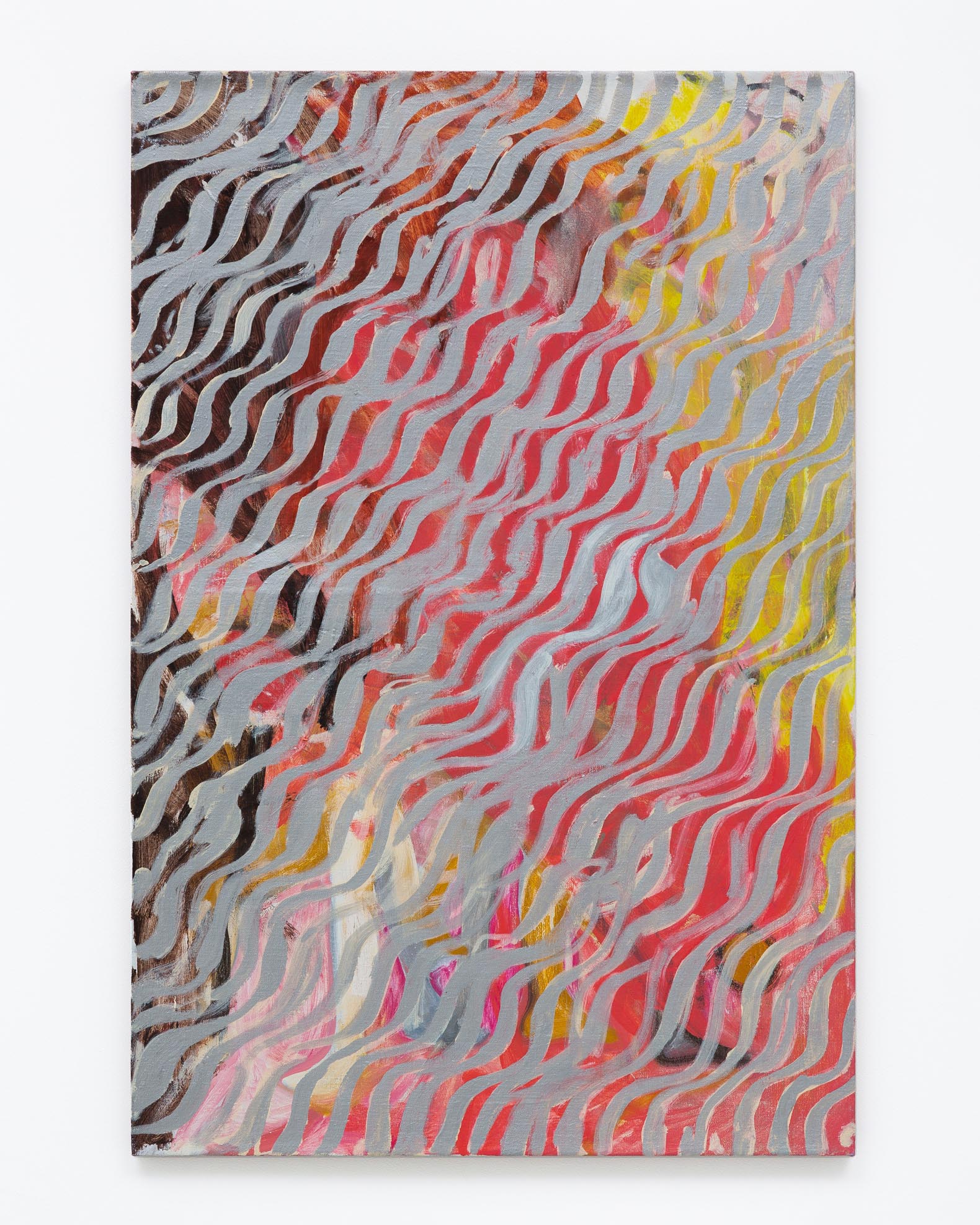

Emma McMillan first encountered Susanna in the margins of Paul Rudolph’s archive. Susanna is the footnote to a mural he produced in 1966 for 101 East 63rd Street, a townhouse designed for Sonny Turner and Alexander Hirsch. The residence was “a world of its own, inward looking and secretive,”[1] an ingenious spatial solution to the exigencies of living a closeted life in the 1960s. It had an austere public face, but an exuberant interior – a sky-lit, multi-story atrium with a lounge, library, bedroom, stairs, and catwalks vertiginously perched on cantilevered steel platforms. To formally and symbolically anchor the space, Paul Rudolph painted a mural depicting men throwing stones amidst an abstract landscape of hills, trees, and streams. This was copied from a wedding chest, illustrated with the apocryphal story of Susanna, painted by Domenico di Michelino in the fifteenth century. An abbreviated version of the story goes: Susanna was a young woman who was falsely accused of infidelity after two old judges harassed and blackmail her. She was saved from execution by Daniel, whose divinely inspired cross-examination of the elders exposed perjury. The men who had prepared to kill Susanna about-faced and stoned the corrupt judges. Rudolph isolated the image of the male jury from a wedding chest—namely the allegory of fidelity and packaging of her dowry—as the decorative centerpiece in the home of a same-sex couple. The house was sold to Halston, who liked his environments “white and sparse” and “wanted to take out some things that were just decorative.”[2] The mural was destroyed. In this later chapter, the house became a hub for disco in New York City and a sanctuary for a new elite queer culture. The atrium, the original site of the mural, hosted parties where guests would dance on the platforms and catwalks. The second iteration’s frantic and whirling tone contrasted the ecclesiastical themes of 101’s previous interior. McMillan’s pictures are layered with the iconography of these phases.

Susanna takes its cues from this history. Gothic forms attest to the confluence of spatial awe and morality, a quality Rudolph achieved in his own architecture. The characters excluded from the narrative are represented in either sgraffito, as grotesques subsumed in aqueous fields of color, or engulfed in a white that seems to bleed in from the environment. Susanna’s contemporary position in McMillan’s paintings is like that of a specter. She haunts another Rudolph building. In her after life she is an interlocutor in the discourses on class, gender, and heteronormativity with which her story intersects.

By contextualizing Susanna within the Modulightor, the paintings echo the discord between Modernist ideology and contemporary art, apocrypha and popular culture. Located ten minutes from Rudolph’s iconic townhouse, 101 East 63rd, this exhibition considers how the form and content of McMillan’s works links the two spaces – calling attention to idiosyncratic and significant icons of architecture.

– Eduardo Alfonso

[1] Paul Rudolph, quoted in Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl, and Gerhard Schwab. The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. (New York: Praeger, 1970). 80

[2] Goldberger, Paul. “Halston’s Hideaway,” The New York Times, July 24, 1977.

Emma McMillan (b. 1989, Atlanta; lives and works in New York) gained her BFA from the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 2012. Solo exhibitions: Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, New York; Atlanta Contemporary, Atlanta; Édouard Montassut, Paris; Lomex, New York; Bad Reputation, Los Angeles; Selected group exhibitions: Peter Freeman Gallery, New York (presented by Alex Katz); Praterstrasse 32/308, Vienna; Alyssa Davis Gallery, New York; Swiss Institute, Rome; Lomex New York. The artist’s work has been the subject of extensive media coverage in Artforum, Flash Art International, Guernica, and Mousse, among numerous other publications. Her work is included in the permanent collections of Museum fur Moderner Kunst Vienna and the Albertina Museum.

The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, a preservation and 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is based in New York City. Founded by friends and colleagues of Mr. Rudolph in 2002, its mission has been to facilitate the preservation and maintenance of the remaining structures designed by Paul Rudolph through education, advocacy, preservation easements and technical services.

Visitors must present ID along with proof of vaccination for entry. Proof of vaccination may include a CDC Vaccination Card (or photo), NYC COVID Safe app, New York State Excelsior Pass, NYC Vaccination Record, or an official immunization record from outside NYC or the U.S. (these vaccines are accepted: AstraZeneca/SK Bioscience, Serum Institute of India/COVISHIELD and Vaxzevria, Sinopharm, or Sinovac). Read more about the NYC vaccine mandate at https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-vaccines-keytonyc.page. We appreciate your patience and understanding as we work to keep you safe.

This exhibition is produced in collaboration between the artist, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, and Downs & Ross, New York.