“All phenomena of symptom-formation can be fairly described as ‘the return of the repressed.’ The distinctive character of them, however, lies in the extensive distortion the returning elements have undergone, compared with their original form.”

Sep 08 – Oct 14, 2023

Bad Girls Club

Catherine Mulligan

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

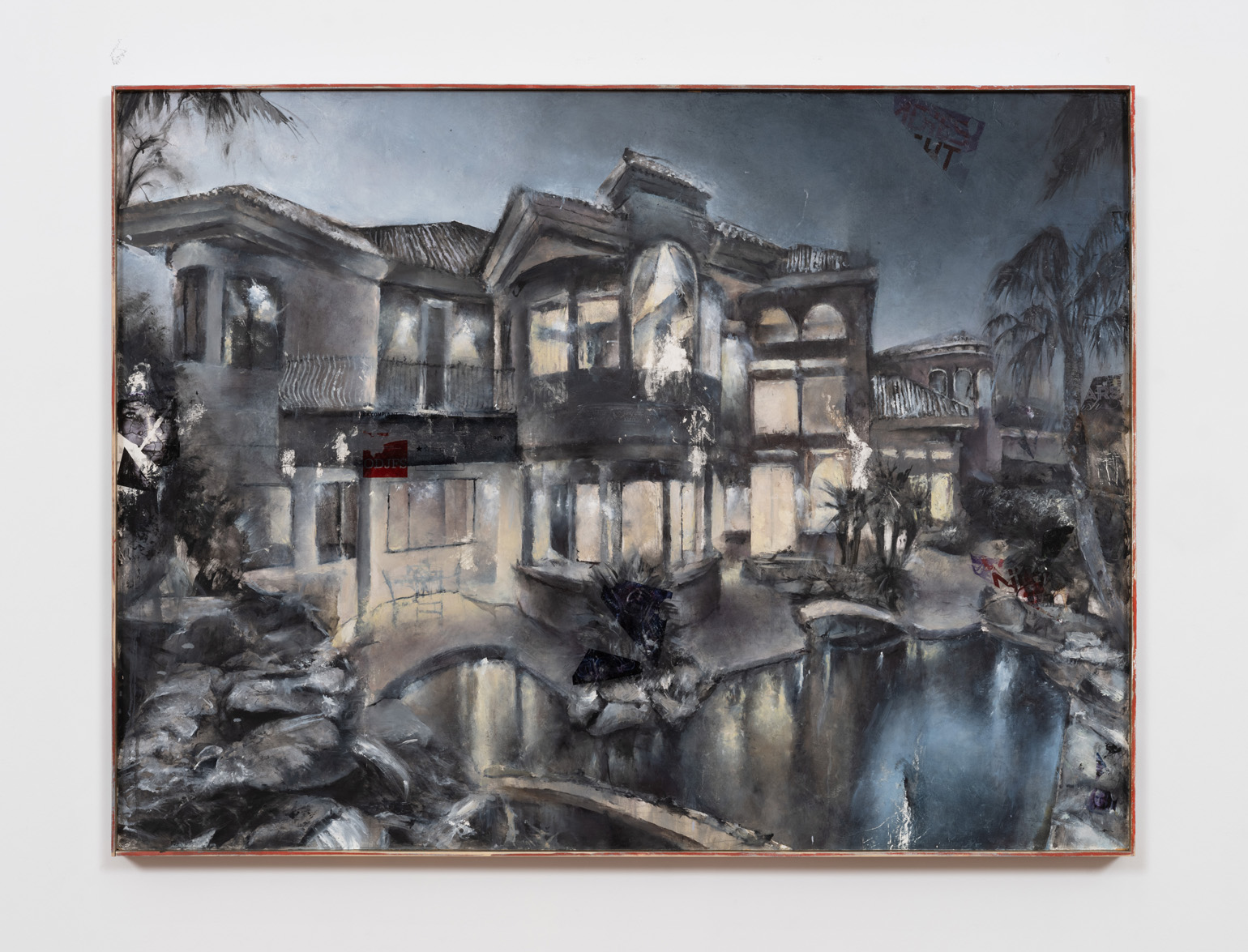

Catherine Mulligan, Las Vegas Mansion , 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 48 1/2 in / 92,7 × 123,2 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Las Vegas Mansion , 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 48 1/2 in / 92,7 × 123,2 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Ass, 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 24 1/2 × 30 1/2 in / 62,2 × 77,5 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Ass, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 24 1/2 × 30 1/2 in / 62,2 × 77,5 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

Catherine Mulligan, Interior , 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 48 1/2 in / 92,7 × 123,2 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Interior , 2023 (alternate view). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 48 1/2 in / 92,7 × 123,2 cm

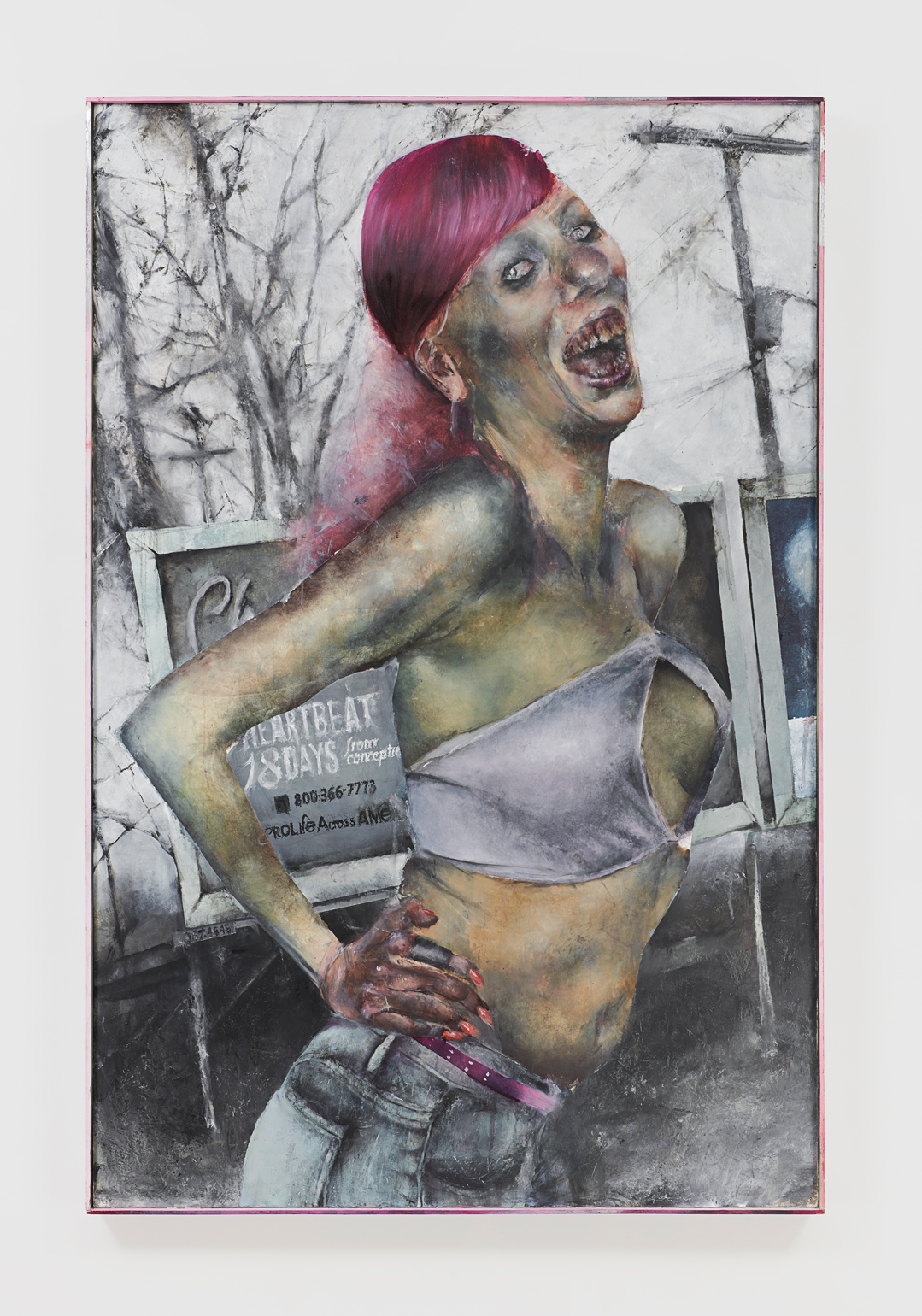

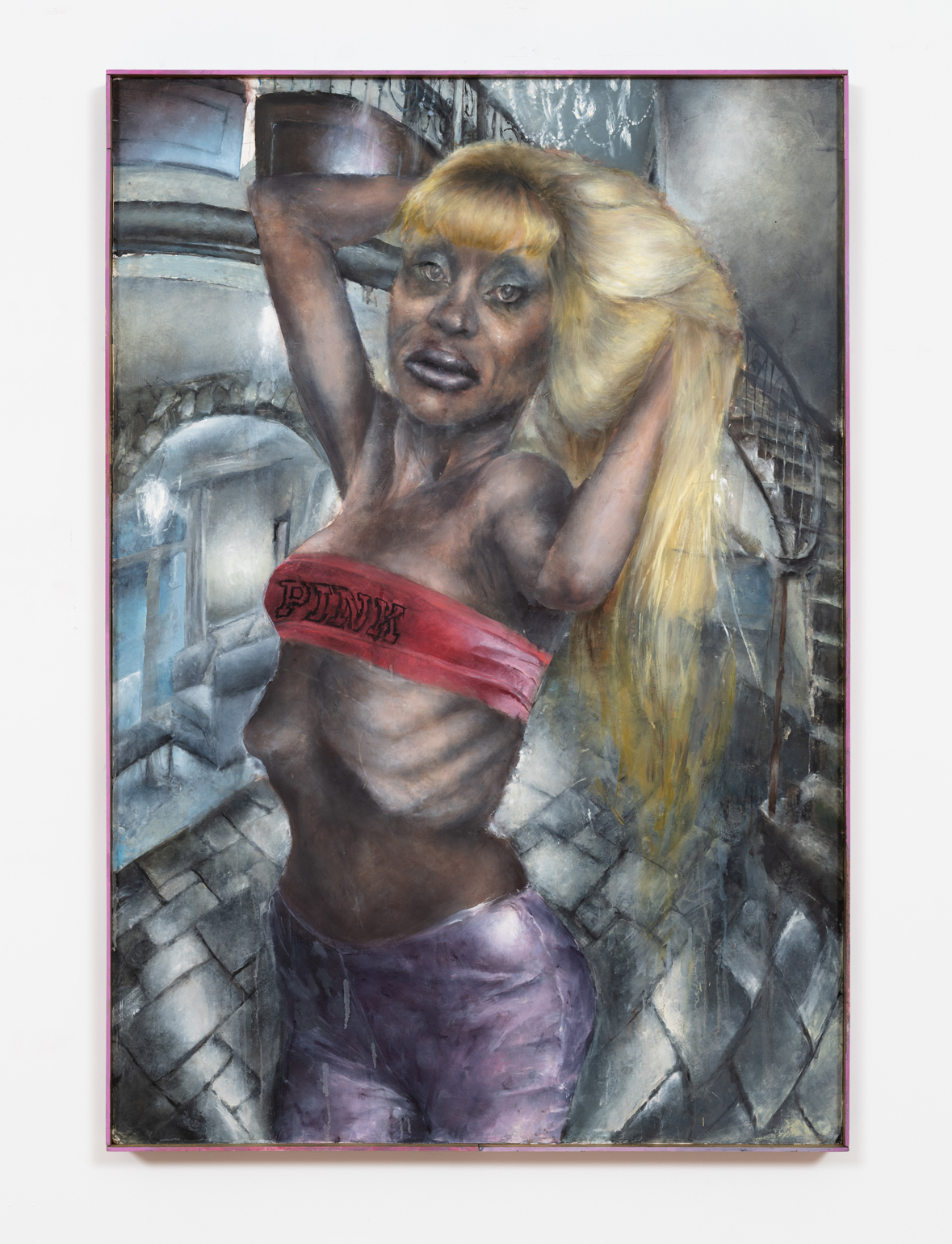

Catherine Mulligan, Hitchhiker, 2023. Oil on canvas with custom frame, 55 1/2 × 36 1/2 × 2 3/4 in / 141 × 92,7 × 7 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Hitchhiker, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with custom frame, 55 1/2 × 36 1/2 in / 141 × 92,7 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

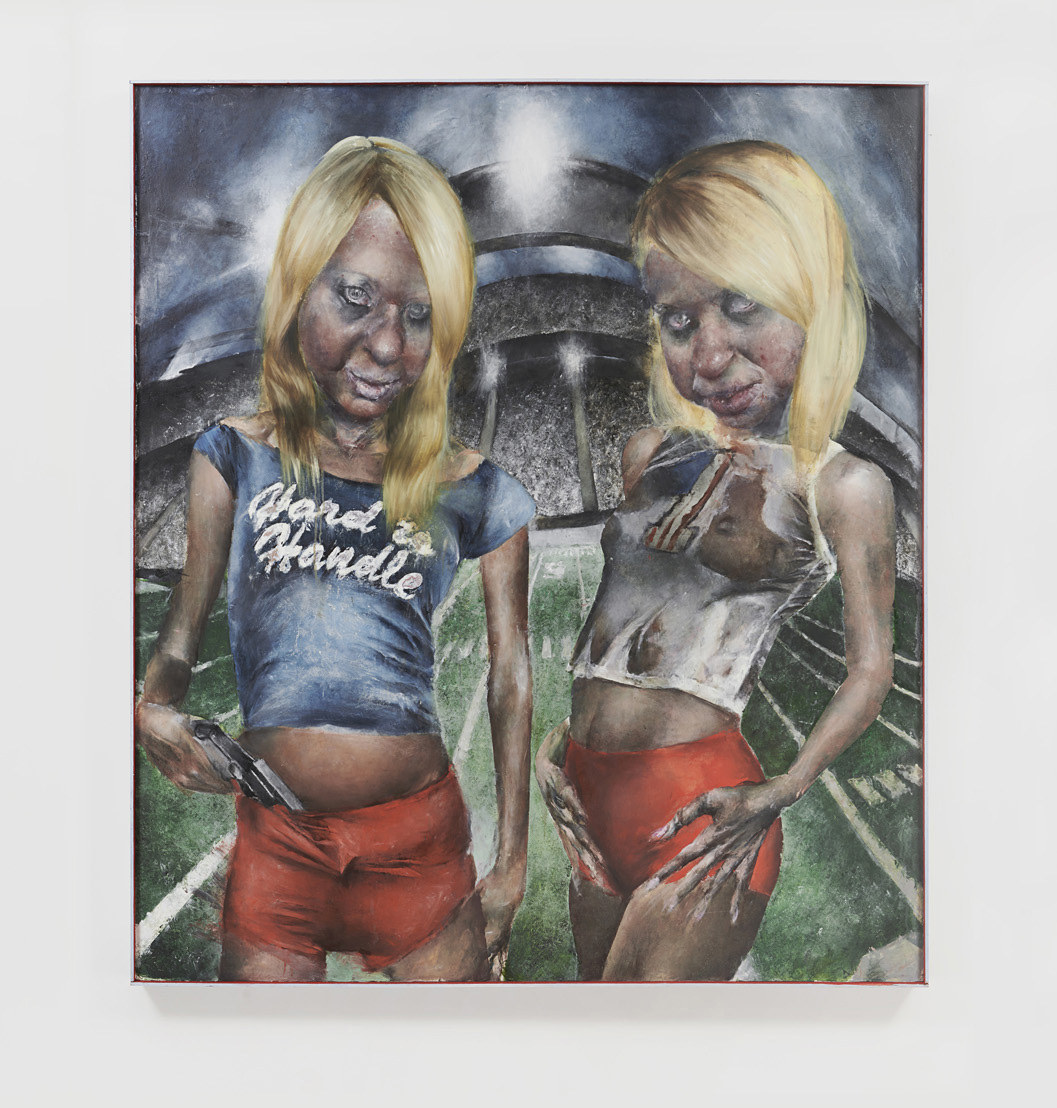

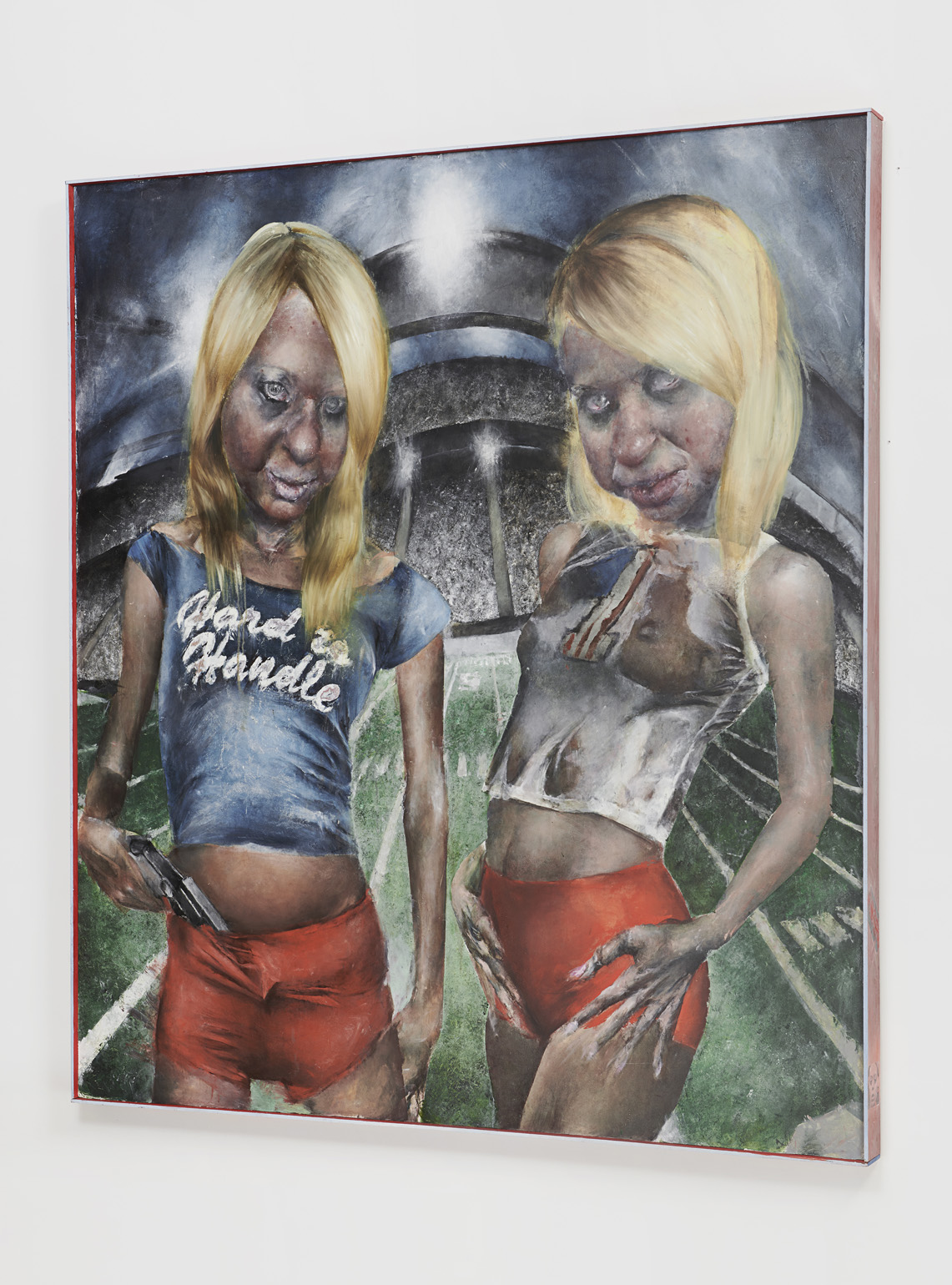

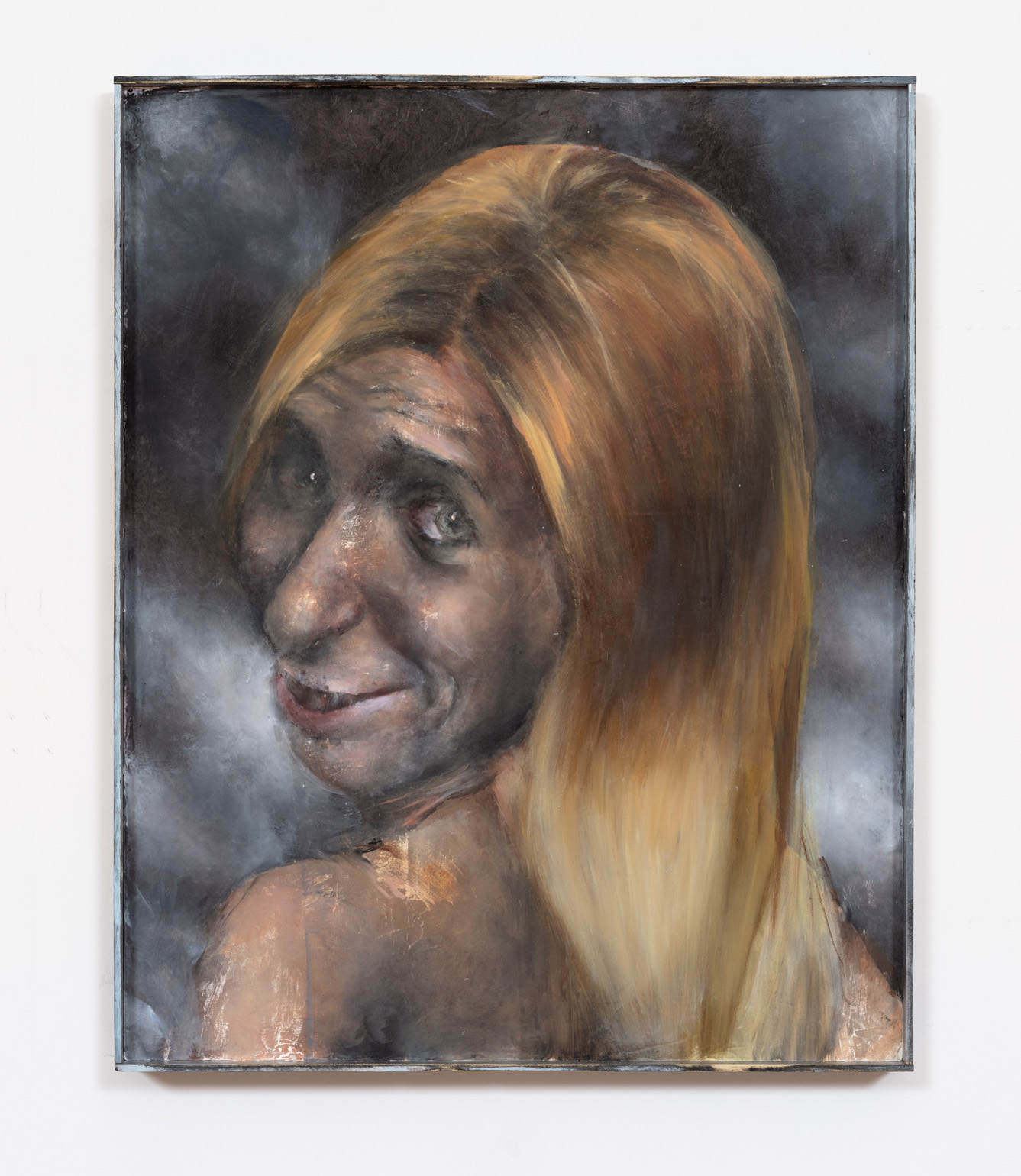

Catherine Mulligan, Blondes, 2023. Oil on canvas with custom frame, 57 1/2 × 50 3/8 / 146 × 127,9 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Blondes, 2023 (alternate view). Oil on canvas with custom frame, 57 1/2 × 50 3/8 / 146 × 127,9 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Blondes, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with custom frame, 57 1/2 × 50 3/8 in / 146 × 127,9 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

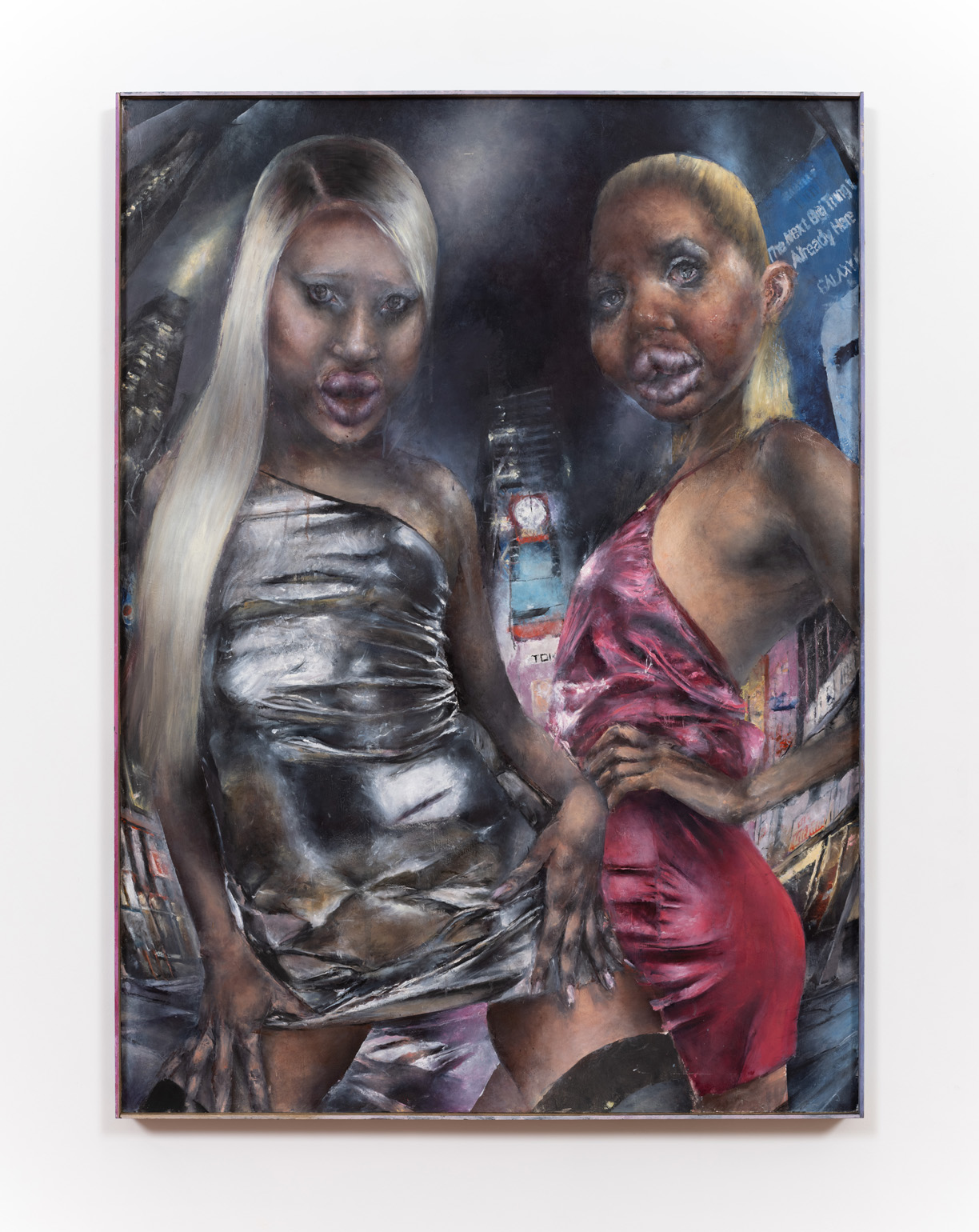

Catherine Mulligan, Nouveau Riche , 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 × 40 in / 139,7 × 101,6 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Nouveau Riche , 2023 (alternate view). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 × 40 in / 139,7 × 101,6 cm

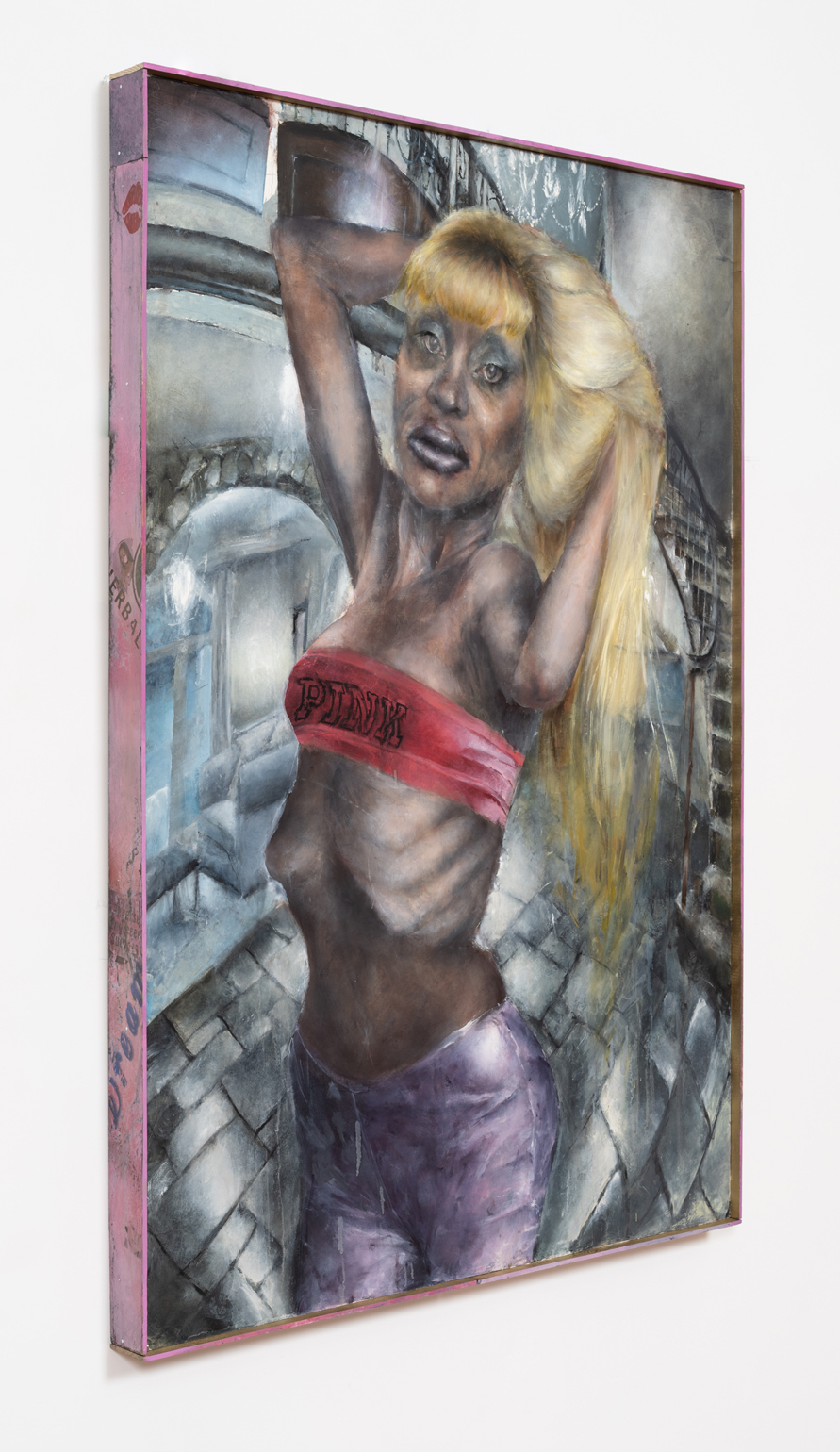

Catherine Mulligan, Nocturne 2, 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 30 1/2 × 24 1/2 in / 77,5 × 62,2 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Nocturne 2, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 30 1/2 × 24 1/2 in / 77,5 × 62,2 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

Catherine Mulligan, Ass 2, 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 24 1/2 × 30 1/2 in / 62,2 × 77,5 cm

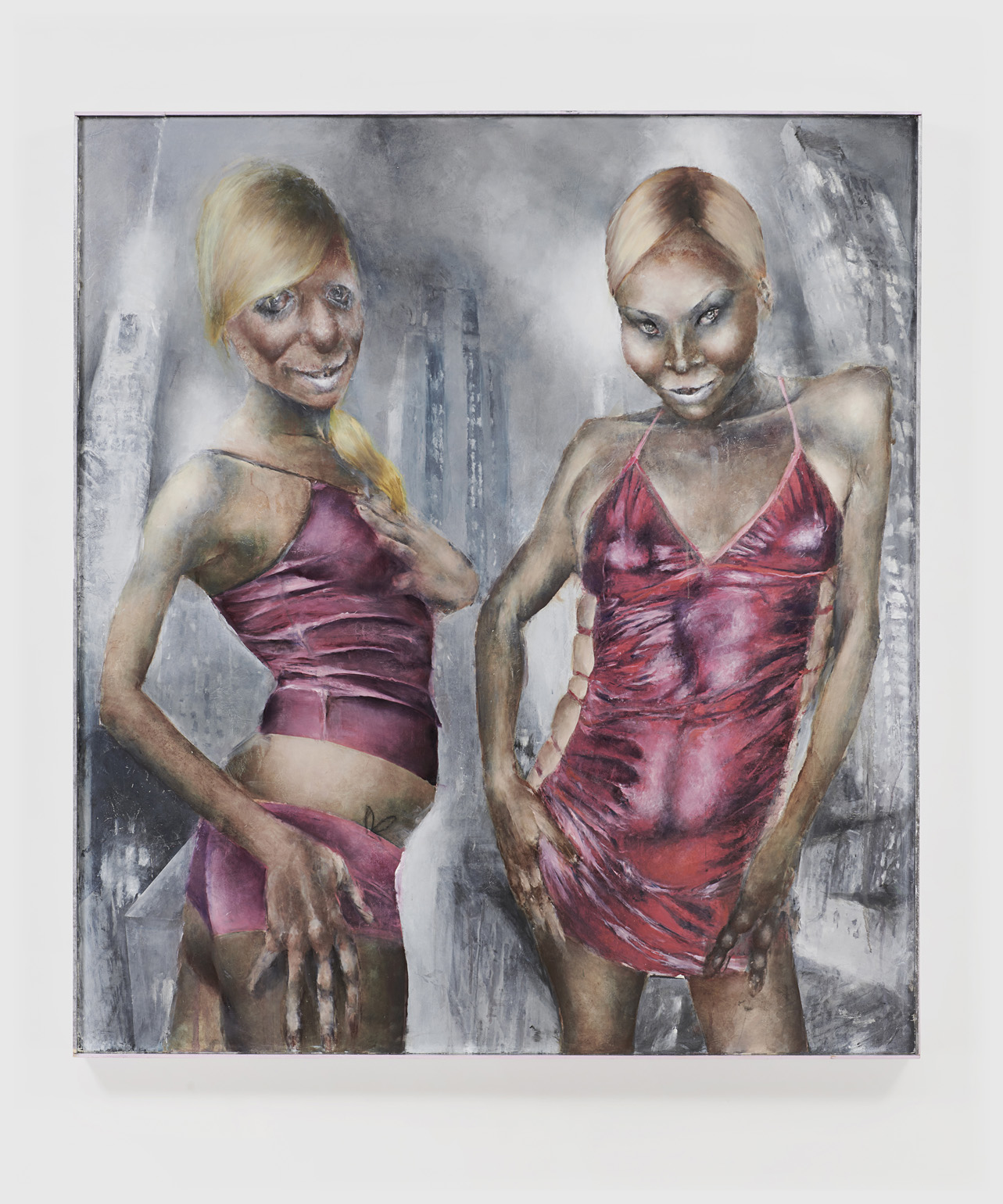

Catherine Mulligan, Clubbers 2, 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 1/2 × 49 1/2 in / 141 × 125,7 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Clubbers 2, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 1/2 × 49 1/2 in / 141 × 125,7 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

Catherine Mulligan, Bridge and Tunnel, , 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 1/2 × 40 1/2 in / 141 × 102,9 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Bridge and Tunnel, , 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 55 1/2 × 40 1/2 in / 141 × 102,9 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Big Brother House (Pool), , 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 30 1/2 × 40 1/2 in / 77,5 × 102,9 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

Catherine Mulligan, Sisters, 2023. Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 32 1/2 in / 92,7 × 82,5 cm

Catherine Mulligan, Sisters, 2023 (detail). Oil on canvas with unique frame, 36 1/2 × 32 1/2 in / 92,7 × 82,5 cm

Exhibition view of Bad Girls Club. Tara Downs, New York, 2023.

– Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, p. 201

As the hot weather season, proclaimed in this year’s parlance as “Rat Girl Summer” by a cadre of content creators on TikTok, draws to its natural conclusion, as another tide of IP-driven blockbusters (come on, Barbie, let’s go party) slowly recedes from America’s dwindling multiplexes, as yet another reboot of the culture wars, inevitably staged on the battlefield of electoral politics, resumes its sordid formation, it makes some sense that a new body of Catherine Mulligan’s patently grotesque paintings would manifest, capstonelike, in downtown New York, where such recurrent indicators of the everchanging national mood reliably generate new dispositions, novel ways of posing and positioning oneself within the disorienting smog of contemporaneity.

With Bad Girls Club, the artist’s first solo exhibition at Tara Downs, Mulligan retrieves us from the current malaise, the implacable mundanity of the Biden era, and returns us to the tomorrow once promised to us, the future that never quite arrived. Framing this regressive moment through the lens of young adulthood, Mulligan populates her works with latter-day demimondes, figures whom almost always arrive equipped with suburban signifiers or bridge-andtunnel accoutrements, regardless of whether they organically inhabit their roles or merely play at them. In one of the works on view, Blondes, 2023, two bobbling figures of Bratz-doll proportions, dressed in Hooters shorts and distressed graphic tees, pose in front of a kind of Futurist rendition of an American football stadium. Together, the twins announce the violent ebullience of the exhibition, and not only because one of them is stashing a handgun. As the exhibition’s eponymous bad girls, they in turn allude to the ones we once saw on TV, living and partying with one another, but mostly fighting. If this particular mid-2000’s reference appears somewhat foggy, therein lies the point. Lamenting the demise of monoculture, the sort of consensus required to render the artist’s pop references immediately legible, Mulligan’s strange paintings propose a return to the precise moment of mass media’s disintegration, as a form of hauntological survey, or, more directly, as a homecoming.

For a certain set of Millennial viewers, such works perfectly recall the staid, anemic visual culture of the second Bush years, the fratty films and television shows and fashion editorials that cluttered and stalked our adolescence and arrested us there. They begin to resemble the sort of images gleaned from the activities that marked the short durée of our collective aesthetic awakening: the hours spent perusing periodicals at Borders, the unhurried days spent in front of television sets and laptops at our parents’ hastily constructed McMansions. They exhume the corpse of Marissa Cooper (1988-2006), the teen-soap heroine of The OC, who inexplicably seemed to sulk into every frame from beyond the veil, even before she fatally careened off-screen. They remind us of the nepo-babies Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie, clad in bedazzled Juicy tracksuits and bug-eyed sunglasses, tormenting certain desolate corners of the American landscape. Or, instead, they recapitulate the unheimlich quality of that perennially viral image of Chloë Sevigny and Maggie Gyllenhaal, two prominent actresses and It girls of the early aughts, mugging languorously in sporty Chanel and Lacoste ensembles at the 2004 opening of – yes, that’s correct – the Atlantic-Barclays Target. Comparable step-and-repeat photos, alongside vintage Steve Madden ads, Dipset-era mixtape covers, and botched before-and-after cosmetic surgery pics, constitute the foundation of the artist’s endlessly recursive, high-low regime. It is as if Mulligan stumbled upon a sizable cache of such half-remembered evocations – vestiges of a bygone cultural moment – sequestered in Dorian Gray’s attic for the past twenty years, and gleefully set about transcribing the results.

Hers are paintings that reanimate the undead and deploy them in service of a singularly lugubrious vision, a transgressive fairytale reimagining of the recent past, or, perhaps, a comically literal take on the often pejorative term “zombie figuration.” While Mulligan’s past paintings in oil depicted similar stock characters – models who bore some semblance to the second-rate stars of tabloid and reality TV – the disjunctive backdrops of her recent works have become more intrinsic to their meaning, more pointedly tethered to current events and their consequential debasements. In Hitchhiker, 2023, the livingdead subject of the painting bends and snaps against a grisaille landscape, an autumnal scene punctured by a yard sign advertising the anti-abortion services of ProLife Across America, legible between the crook of the main character’s posed body and bent arm. Elsewhere, Mulligan abandons her signature figures entirely, preferring instead to present vacant architectural scenes redolent of the establishing shots of long-running reality TV shows like Big Brother and, indeed, Bad Girls Club, where the improvised, real-time construction of the program’s narrative is mirrored by the ad-hoc staginess of the set.

A small wonder resides in Mulligan’s confluence of these low genre tropes and the highly amalgamated artistic lineage she has constructed for herself, which a propensity for bawdy figuration quite distinct from the minor genre’s leading proponents, a group that would invariably include major contemporary artists like John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage. Like those two, Mulligan is ultimately a painter’s painter, pressing firmly at the medium’s pictorial boundaries, even as she rests well within its established parameters. Unlike them, however, Mulligan’s seems to locate her raison d’être in the allegorical possibilities of cultural types rather than the pleasures and repulsions of the body itself. And what better form for stripping away the pink, plastic veneer of American life than that of the jeune fille, who is always centrally involved in cultural signification anyway, even if, and especially when, we wish it weren’t so. Channeling the return of the repressed? Bad girls do it well.

– Jeremy Gloster

Catherine Mulligan (b. 1987 in Nutley, NJ) lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She gained her BFA from University of Pennsylvania in 2010 and her MFA from Indiana University Bloomington, in 2019. Her work has been exhibited at "Bad Girls Club," Tara Downs, New York, US (2023); "Vanitas," Queer Thoughts, New York, US (2022); "Legally Blonde," Tara Downs, New York, US (2022); "Security," M+B Gallery, Los Angeles, US (2021); "Jahresgaben 2021," Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, DE (2021); "Nightcore," Envy6011, Wellington, NZ (2021); "Fade Into You," A.D. Gallery, New York, US (2020); "VOX XII Annual Juried Exhibition," Vox Populi, Philadelphia, US (2016); and "Keeping It Real: Recent Acquisitions of Narrative and Realist Art," Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, US (2015), among other venues. Mulligan has been the recipient of two Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grants. Her work is included in the permanent collections of the Woodmere Art Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.