A fixture of New York’s Cedar Tavern during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, and a regular contributor to Artforum in the decade following, Budd Hopkins (1931–2011) cultivated a close proximity to the shifting centers of New York’s art world. Working alongside AbEx – indeed, personally alongside artists like Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell – but never succumbing to the dogmatic conversation surrounding it, Hopkins dedicated himself, in both writing and artistic practice, to a reconsideration of painting’s place in the American century. He leaves behind a dualistic body of work that is both buoyant and solemn, gestural and rigorously formal, opening up the often hermetic character of mid-century abstraction to a multitude of associations.

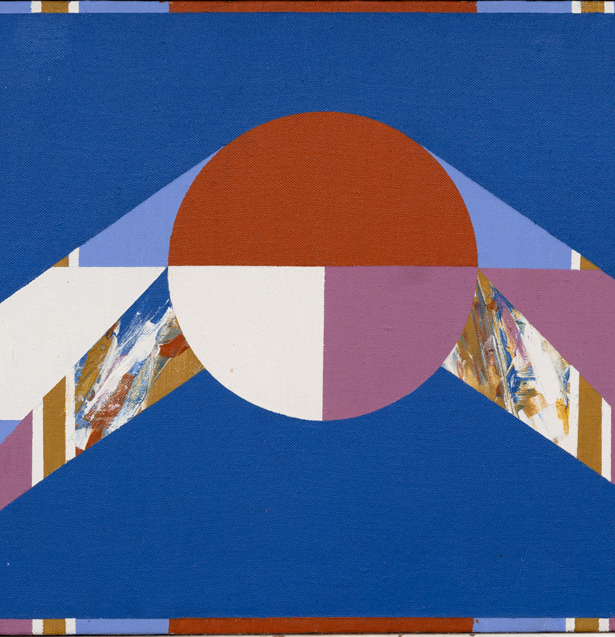

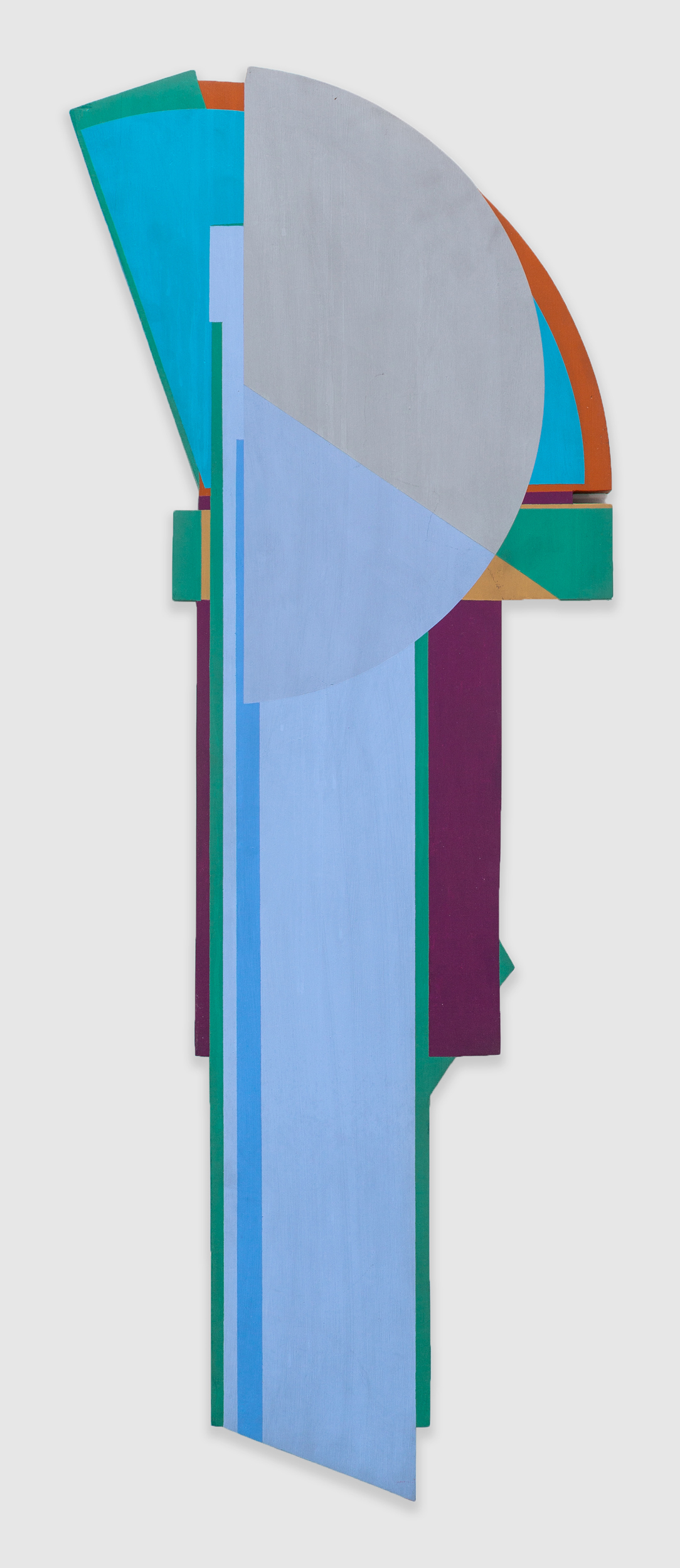

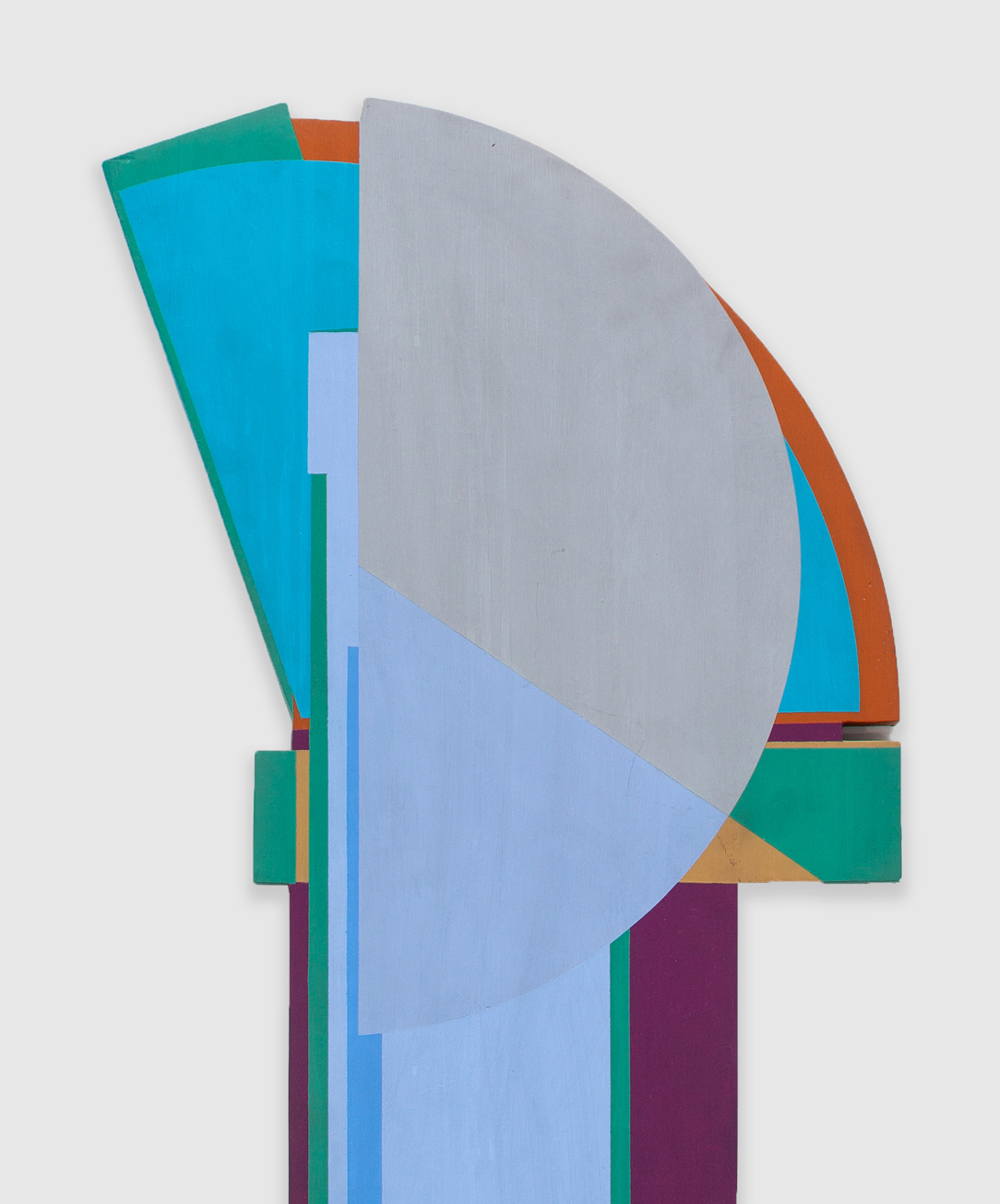

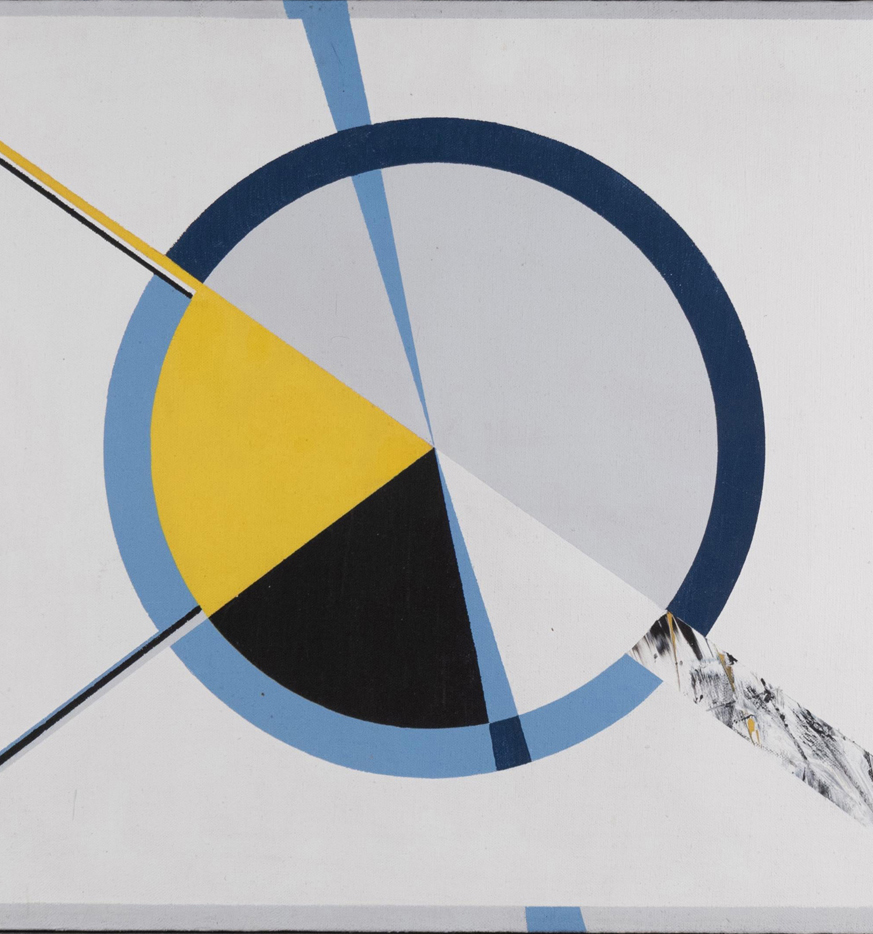

Guardian borrows its title from a series of paintings Hopkins began in the late 1970s and revisited periodically for the remainder of his life. Abandoning the discrete rectilinear panels by which he produced his “assembled paintings” earlier in the decade, Hopkins began painting in oil on custom-made panels, drawing the works closer to the vernacular of architecture, and closer toward objecthood, away from purely pictorial considerations. These works have occasionally been seen to mark the end of Hopkins’ engagements with AbEx, an engagement most evident in early works such as Untitled Tondo, 1963. Such moments of painterly expression became increasingly compartmentalized within the artist’s program of geometric abstraction throughout the second half of the 1960s and the better part of the 1970s, culminating finally in the Guardian series. Yet demonstrating the recursive nature of Hopkins’ practice, and its aforementioned dualism, another Guardian, 1981, finds the artist both returning the geometric forms of the earlier Guardian works to the conventional canvas and reverting to an expressionistic mode of production, in this case betraying the conspicuous influence of Franz Kline. From our current vantage, the privilege to survey the work in total, this sort of self-reflexive reconsideration of the past would become characteristic to Hopkins’ oeuvre. Indeed, Guardian anticipates Hopkins’ prolonged return to his distinct form of expressionism in the late 1990s.

By the time of Guardian’s initial appearance, Hopkins had already published, in the Village Voice, his first investigation into the phenomenon of alien abduction, establishing a field of scientific study and launching a second career as a ufologist. Although Hopkins assiduously denied any correlation between his artistic practice and his subsequent research in ufology, for which he is often remembered today, we might instead note that sensory information – certain discoveries of the concealed, intangible, or unrepresentable facets of experience – motivated his work in abstraction from the beginning. Moving from West Virginia via Oberlin College in the mid-1950s, the foreign rhythms of city life and its strange geometries provided the experiential, emotive terrain upon which Hopkins could distinguish his burgeoning practice from the formative milieu in which he situated himself. “Abstract Expressionism was winding down, and though I was, in my own work, looking for something cooler, more stable, more orderly, I was reluctant to give up the fervid New York energy that quivered in every Kline and Pollock and de Kooning,” the artist wrote later, in 1976.

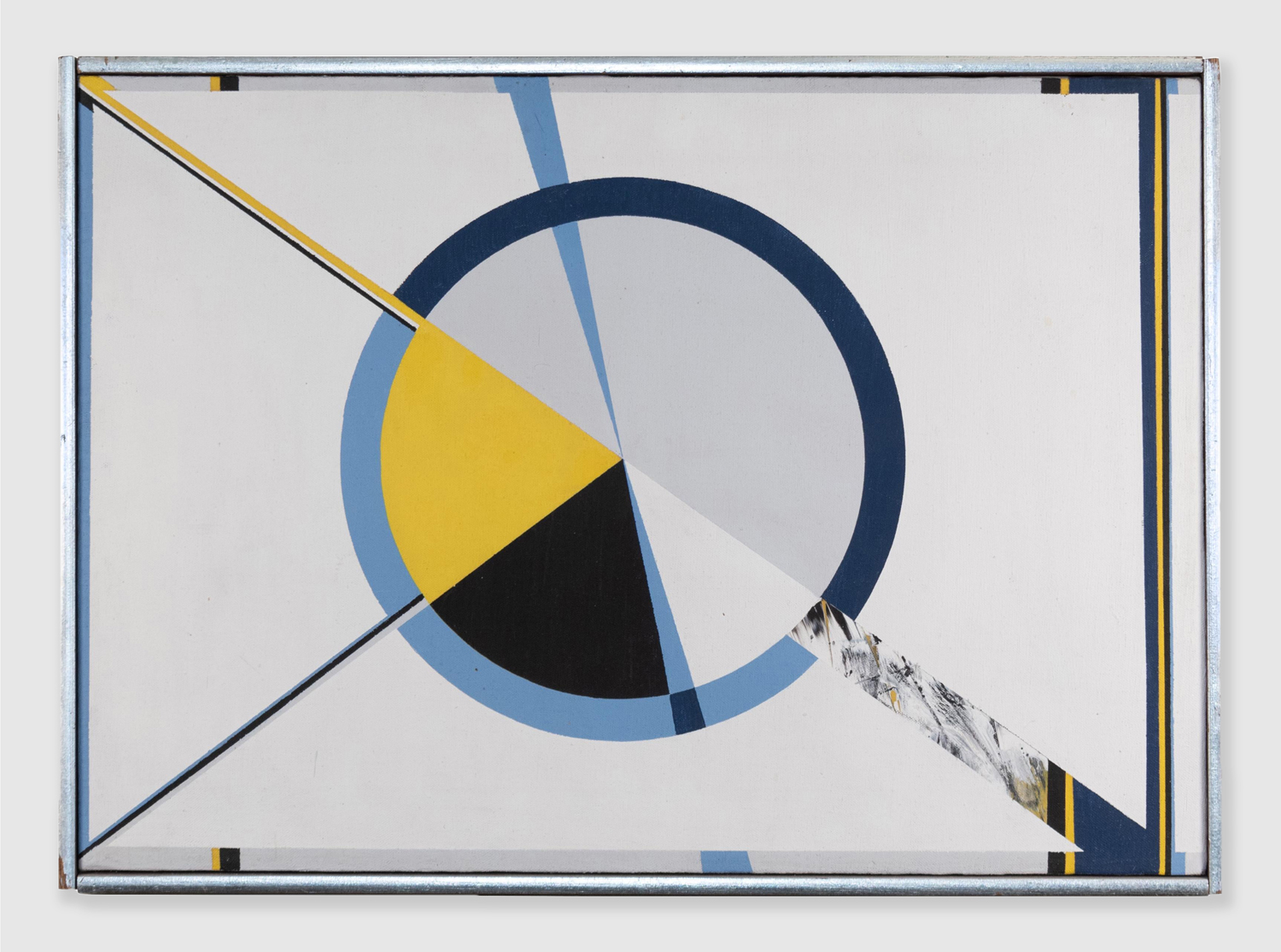

Kline and Pollock and de Kooning – these are among the names who inform Hopkins’ highly combinatory practice. To this list we might add Mondrian, whose sense of geometric abstraction lend Hopkins’ paintings their structuring force, and Matisse, who often inspired these works’ brilliant sense of color. With City Slant, 1974, the “fervid energy” of urban life becomes the subject of the work itself: washes of stone, marble, and cement grey intrude on the characteristic array of primary reds, blues, and yellows, and the arrangements of form begin to suggest a mechanical process we cannot quite grasp. Although the work transcends its influences, it remains willfully inscribed in them. At the time, the critic Roberta Smith wrote that, “once you start thinking about the parts of these paintings on their own, it’s obvious that Hopkins is merely combining other people’s styles without adding enough of himself, despite his color and his craftsmanship.” Yet what was once read as mere pastiche now appears prescient, a harbinger of post-conceptual painting practices, particularly that of Peter Halley, emergent in the second half of the 1980s. Early on, these works on view demonstrated the means and strategies by which painting could sustain itself, indeed convincingly address itself to the public, once the scaffolding of formalist modernism and its attendant discourses had been disassembled. The logic of collage, the practice of juxtaposition, and the construction of multiple, co-existent systems within a single work all provided Hopkins with passageways of escape from the totalizing impulse of the artists he admired, those who directly preceded him.

Tropaz, 1969, the exhibition’s monumental centerpiece, evinces the disjunctive logic animating Hopkins’ practice. Crystallizing collagist experiments into a unified field, Topaz pairs flat, interwoven planes of color that seem to conceal another, more expressionist work beneath. All are subsumed by the central, often recurrent, motif of the dominating solar form. We begin to name the appropriate references – Frank Stella, Jackson Pollock, Josef Albers – and then such associations begin to fade. The cosmology of forms overtakes us and we find ourselves in an alternate landscape, composed of flat surfaces rendered in dusty pink and purple navy, cool shades of turquoise and emerald green. Relinquishing ourselves temporarily in front of Tropaz, we begin to glean what Hopkins intended when he disavowed a purely aesthetic interpretation of his work – that each painting holds its own evocative tentativeness, a unique emotive tenor, and, finally, within it, “a sense of arrival.”