“All these calculations yes explanations yes the whole story from beginning to end yes completely false yes” proclaims the mud-bound narrator of Samuel Beckett’s 1961 novel How It Is as he reckons with the inscrutable bounds of interiority, the arrival of form from formlessness, the way time functions within and without us. The novel is entirely without punctuation; it shirks off any responsibility to exclusive meaning.

The totemic work of Budd Hopkins (1931–2011) arrived in this spirit—his paintings and sculptures seem to evade punctuation, insisting yes and…

You might know Hopkins the abstract expressionist or Hopkins the ufologist—and if you are familiar with both, you might know the artist disavowed any connection between these two investments. Hopkins was a mainstay of New York’s Cedar Bar in the 1950s and 60s alongside Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Franz Kline. He was a regular contributor to Artforum from 1975 to 1979 and he forged a rigorous body of criticism dedicated to the status of painting. But in 1976, the artist became something of a cult figure in the investigation of alien abduction when he began publishing on the subject in the Village Voice. He eventually wrote four books on extraterrestrial invasion, and pundits in the field Whitley Strieber and Harvard psychiatrist John Mack credit him with sparking their interest in the phenomenon. In Third Street Red at Downs & Ross, as the gallery’s inaugural solo exhibition of works from the Budd Hopkins estate, a presentation of six paintings and two mobiles spanning 1969 to 1978 offers a reckoning with the artist’s practice on its own terms.

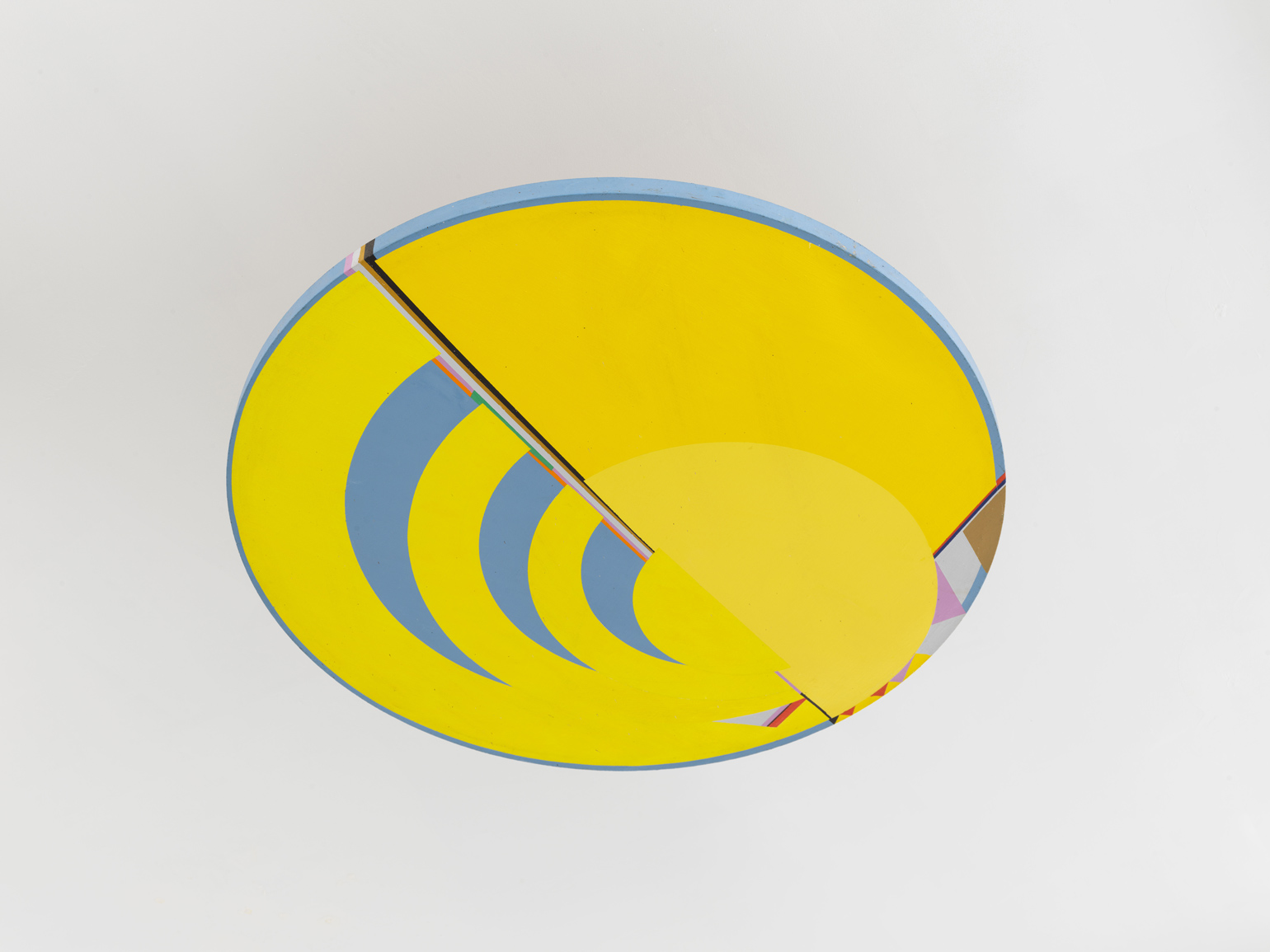

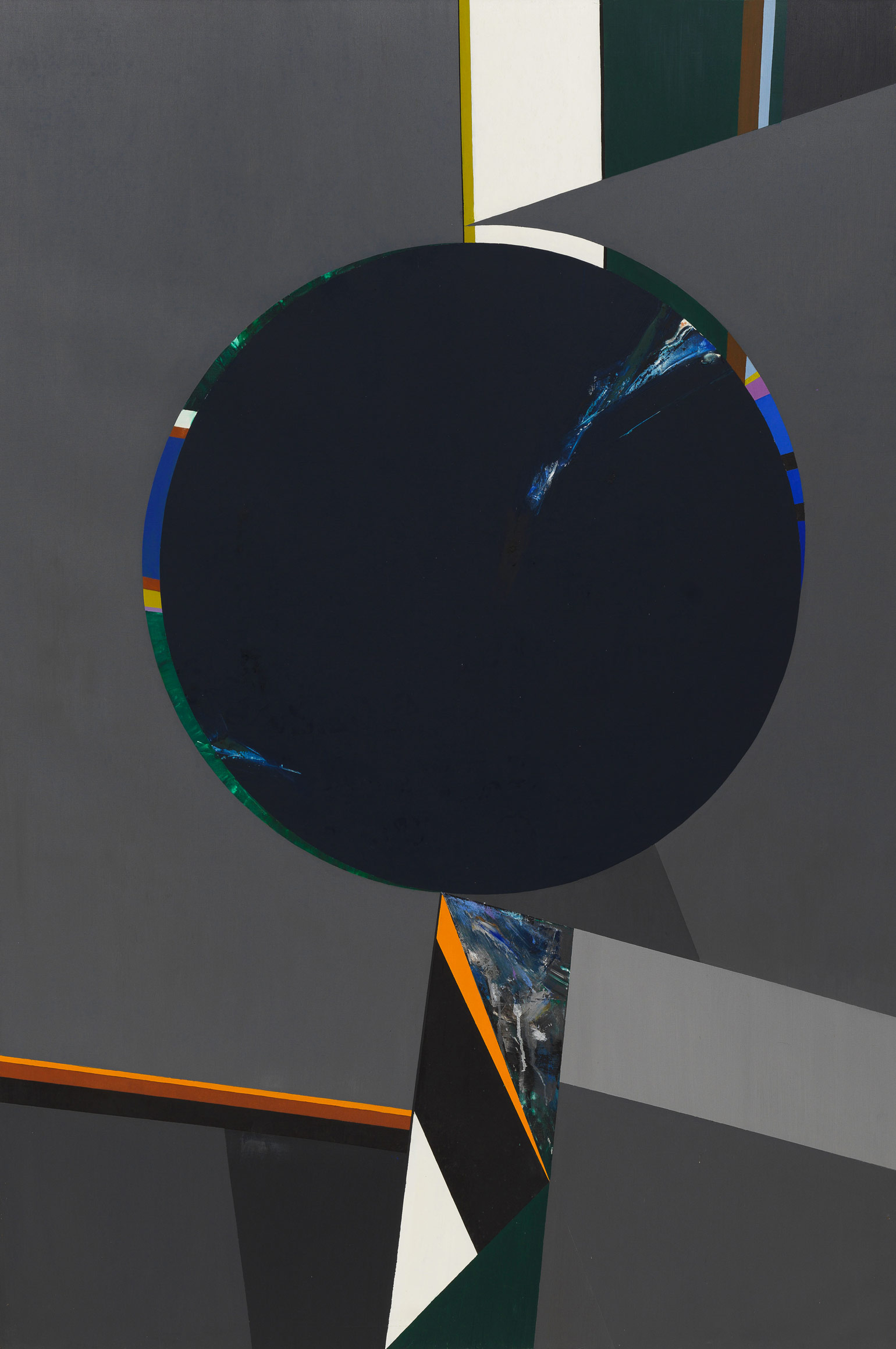

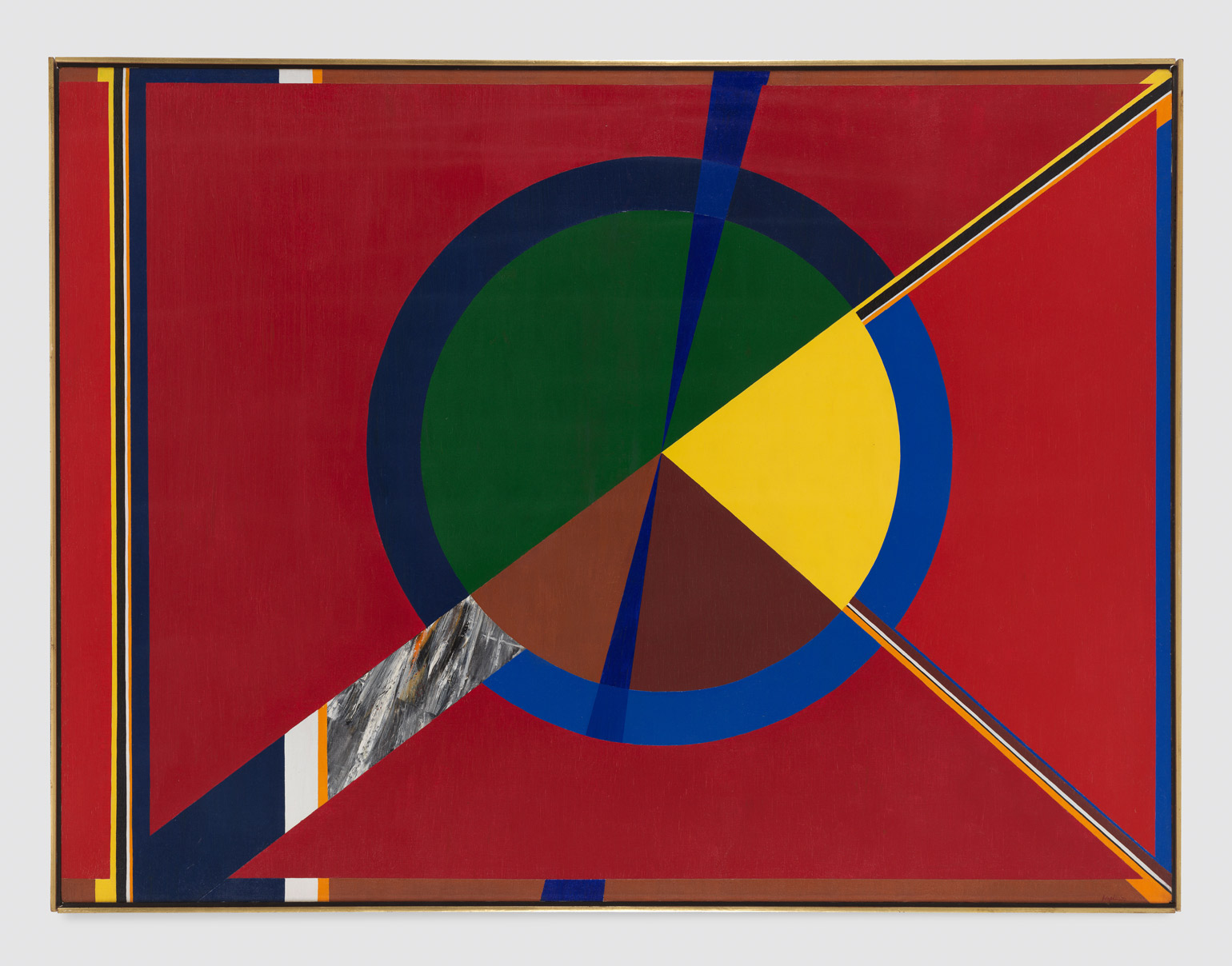

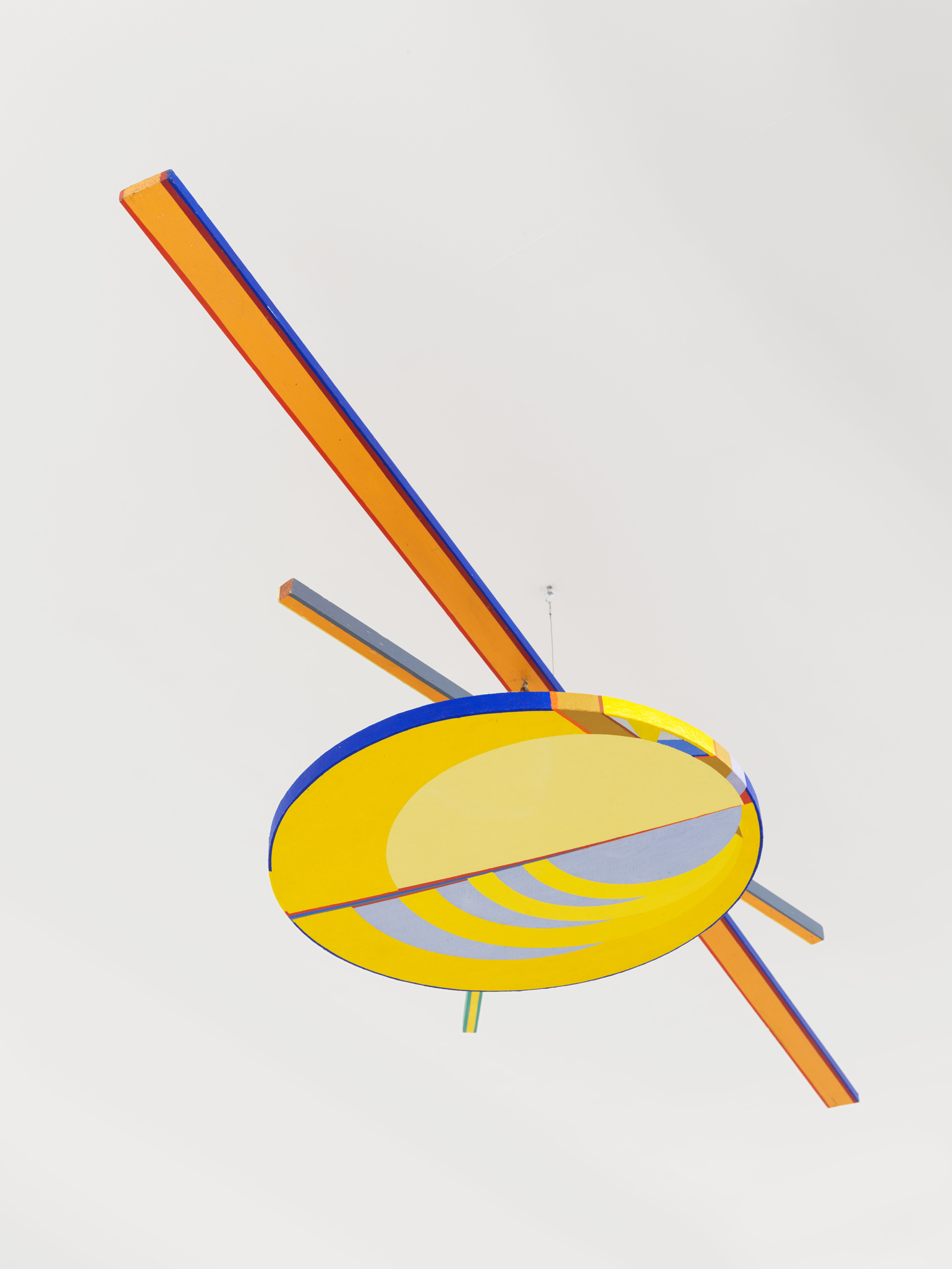

Indeed, there is a superficial dualism built into Hopkins’s identity and his work alike. His mature paintings arrived in the early 1960s with the combinatory impulses of late-modernism, via Fernand Leger’s Cubism, El Lissitzky’s prouns, and Kenneth Noland’s flatbed targets. But they aren’t ahistorical pastiches. His canvases—in southwestern or Memphis design-like palettes of bold primary colors augmented by muted hues—feature hard-edged geometric compositions interrupted by searing passages of gestural abstraction. The latter moments are rendered such that they appear to inhabit a plane under that of the flatly painted forms, which themselves create optical illusions. In Tropaz, 1969, for example, a central lavender circle shares a plane with a fractured mauve ground, which is bifurcated just below the painting’s center horizon. Each resulting half is painted so that a slightly uneven border with the canvas’ edge reveals planes of forest green and turquoise underneath. These verdant planes are subsequently partitioned by stripes of yellow, orange, and umber. None of these geometries align—the eye is perpetually thrown off mark. Just below the central circle, the mauve breaks into tooth-like shapes to make way for a view to brushy white impasto. In one of the painting’s suggested dimensions, an “all-over” lurks. Hopkins’s pictorial spaces assemble and then contradict and unravel the very internal logic of the assemblage. And in this way, the viewer is foreclosed from registering any one gestalt.

One might liken the hybrid logic of these paintings—nearly sculptural in their approach to space—to Frank Stella’s efforts of the late ’50s, but unlike Stella’s impassive pictures-as-objects, Hopkins maintained a hierarchical orientation and a sense of scale in his work. Although his shapes are at times motivated by the format of the canvas, at others, they undermine that very logic, creating a strong figure-ground opposition that in turn is disrupted by yet other suggested dimensions. These sleights shuttle the viewer between central and fringe passages, provoking an appraisal of what is prioritized in perception.

Hopkins’s hard-edged forms are unpretentious in their materiality—passages are stained with domestic paint, revealing the grain of the canvas below, or sections of chalky acrylic flatly admit the brushwork that composed them. But the areas of expressive gesture often have the additional effect of trompe l’oeil, mimicking in oil paint the fractured surface of marble. If Hopkins meant to make reference to this classical material in the marginal under-passages of his paintings, it may have been to suggest that, in the background of all our design is the urge toward reason.

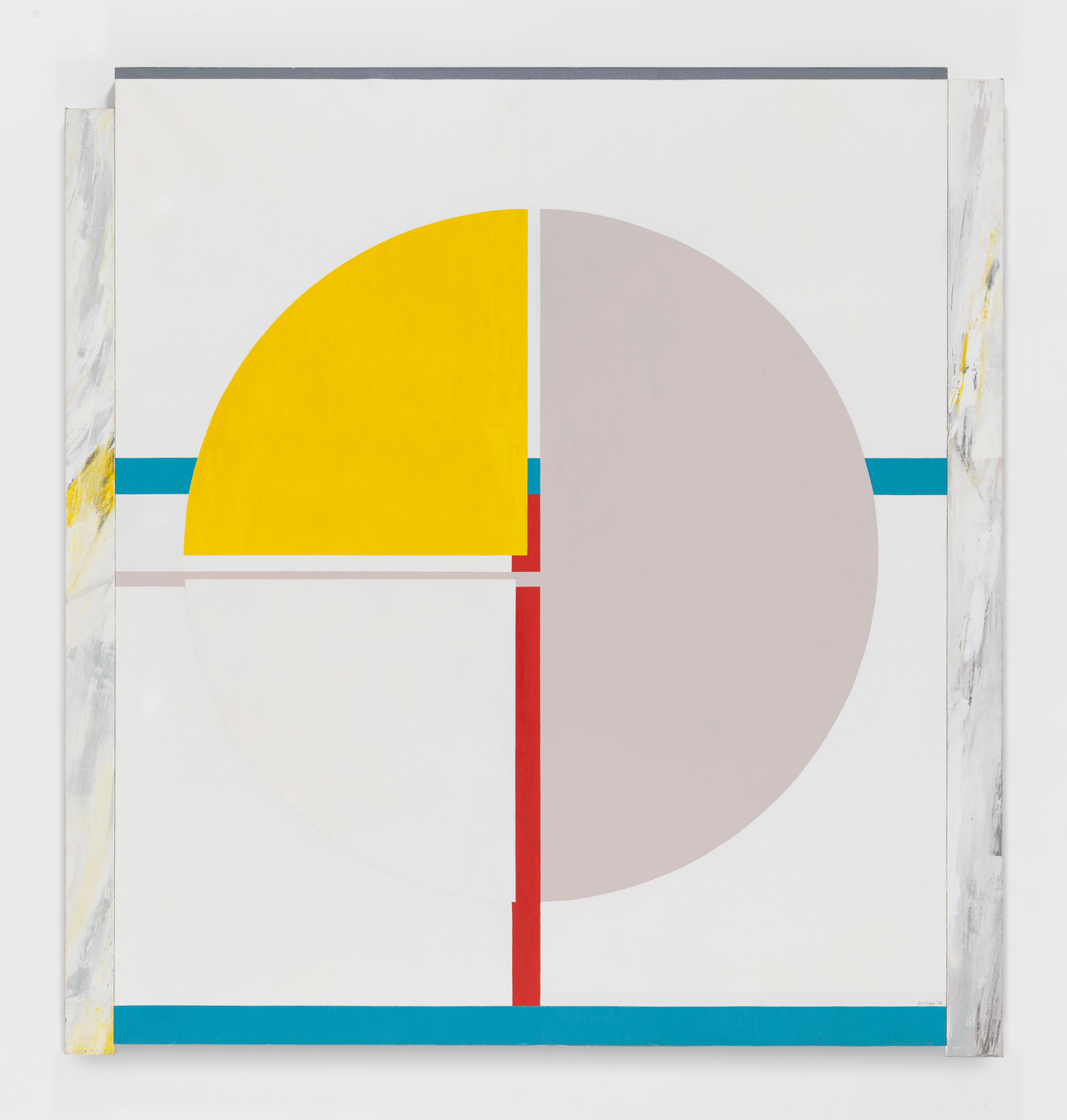

In the early ’70s, Hopkins expanded the disjunctive rhetoric of his paintings by incorporating several discrete canvases into single works. White City Wall, 1974, comprises a square flatly-painted canvas, white with an intervening gray and yellow circle, flanked by two narrow, gestural canvases that are mounted to its sides. Mondrian-like lines of cyan and red divide the central canvas, and a thin horizontal grey line is painted at its top, suggesting an improbable shadow and creating a register at which the top of the right columnar canvas begins—the top edges of these conjoined canvases do not level with the central one by significant margins. As is also made explicit in the five-canvas construction Hera’s Wall Temple, 1978—in which painted lines of varying weights obscure the actual seams between canvases—this body of work takes the structural exploration of Mondrian and makes it architectural.

Hopkins owed a great deal to Mondrian’s neoplasticism; he wrote of his admiration for the Dutch painter’s implication of many coincident systems, and the way he “plays almost perversely with one’s expectations...[involving] the appearance of a grid (suggesting regularity, evenness, etc.) and the actual arbitrary, unpredictable placement of lines.” In most of his paintings, Hopkins sites, just off-center, a predominant circle around which he generates his compositions, testing the ways in which the viewer’s perception of the shape would change according to its surroundings. If Mondrian’s lozenges employed a similar methodology to exhaust the semantic possibilities of a reduced vocabulary of pictorial elements, Hopkins aimed to hold all of these possibilities together at once. “Logic and illogic had to hold their own in the same field,” he wrote in 1973, “the supporting conceptual overview had to be reconstituted in the viewer’s mind.” In this way, he found resolution in dissonance.

The cohabitation of logic and illogic are certainly manifest in Hopkins’s central sphere. In 1964, the artist witnessed, for three minutes, a flat, silver, cryptic object hovering in the skyline of Cape Cod. “When you see something like that,” he wrote “you realize that there's some factor in the world that you had previously been unaware of.” This factor would become the eternally elusive object of his fixation, and it would come to dominate his orientation toward form. After this sighting, Hopkins brought the circle into his work as its primary element.

I read Hopkins’s circle as an after-image—that impression of a sensation that remains after a stimulus or exposure has ceased; the dim area that floats before one’s vision after looking into a light. The after-image has an internal contradiction—it is an obfuscation caused by illumination. It is this very contradiction that Hopkins sought to parse across his projects.

He once claimed that Rothko employed a rectangle in his paintings because of a childhood memory in which his family describes a Czarist pogrom that required victims to dig their own grave. “Rothko said he pictured that square grave in the woods so vividly that he wasn’t sure that the massacre hadn’t happened in his lifetime. He said he’s always been haunted by the image of that grave, and that in some profound way it was locked into his painting…our response to his painting, on some subliminal level, involves our sensing his feelings about that rectangle.” Likewise, Hopkins’s glyph itself may well resemble a saucer, though it could be argued that the circle doesn’t represent a morphological resonance with UFOs, but a functional one; perhaps one on the level of meaning. One of Hopkins’s significant contributions to ufology was the theory of missing time, of temporary amnesia—moments in which the subject suffers an inexplicable lapse in spatialized time that the brain recalls as durationally continuous. In this light, we might see the circle as horological, and the compositions that surround it as attempts to rebuild a missing moment.

In 1977, the critic Carter Ratcliff wrote that “the actualities of Hopkins’s works are ultimately inseparable from the possibilities they exemplify—possibilities for self-consciousness, for the reconciliation of disparities, for the preservation of specific, localized values.” Indeed, these possibilities are still exigent; Hopkins’s work asks us to balance speculation with obdurate fact, and to produce the conditions for heterogeneous realities to coexist.