Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased, the second never totally completed; they are like palimpsests on which the scrambled game of identity and relations is ceaselessly rewritten.”

– Marc Auge, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, p. 79

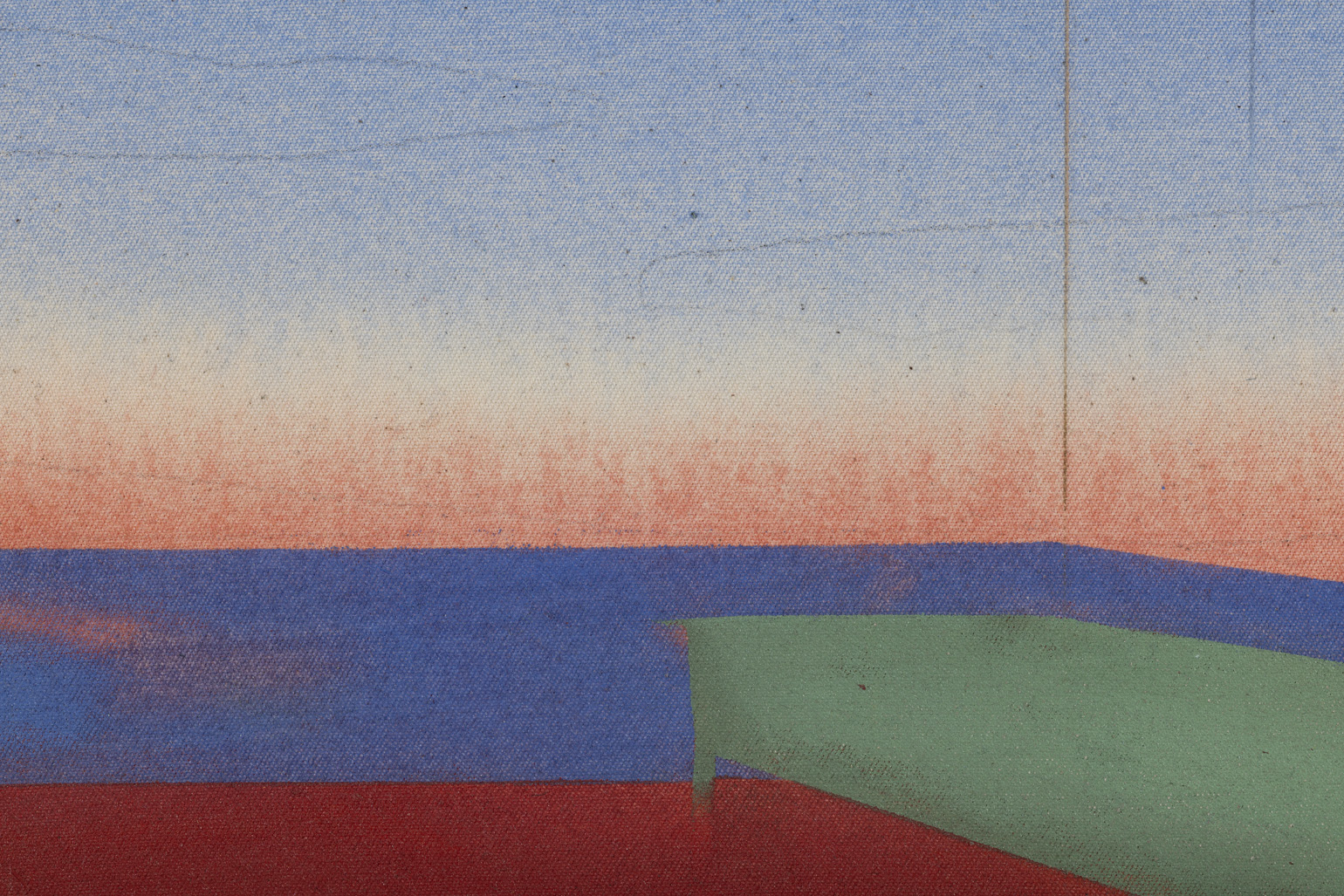

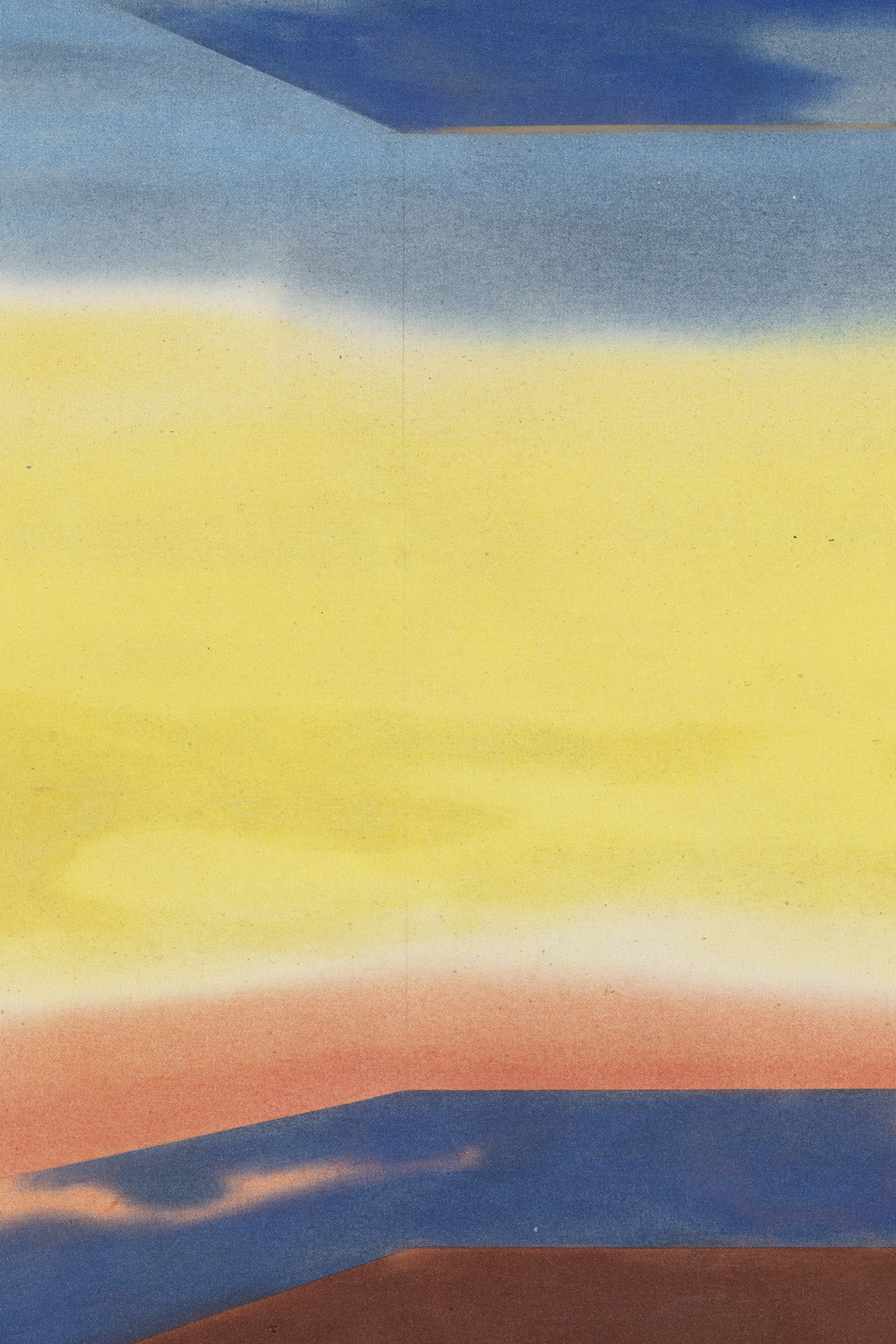

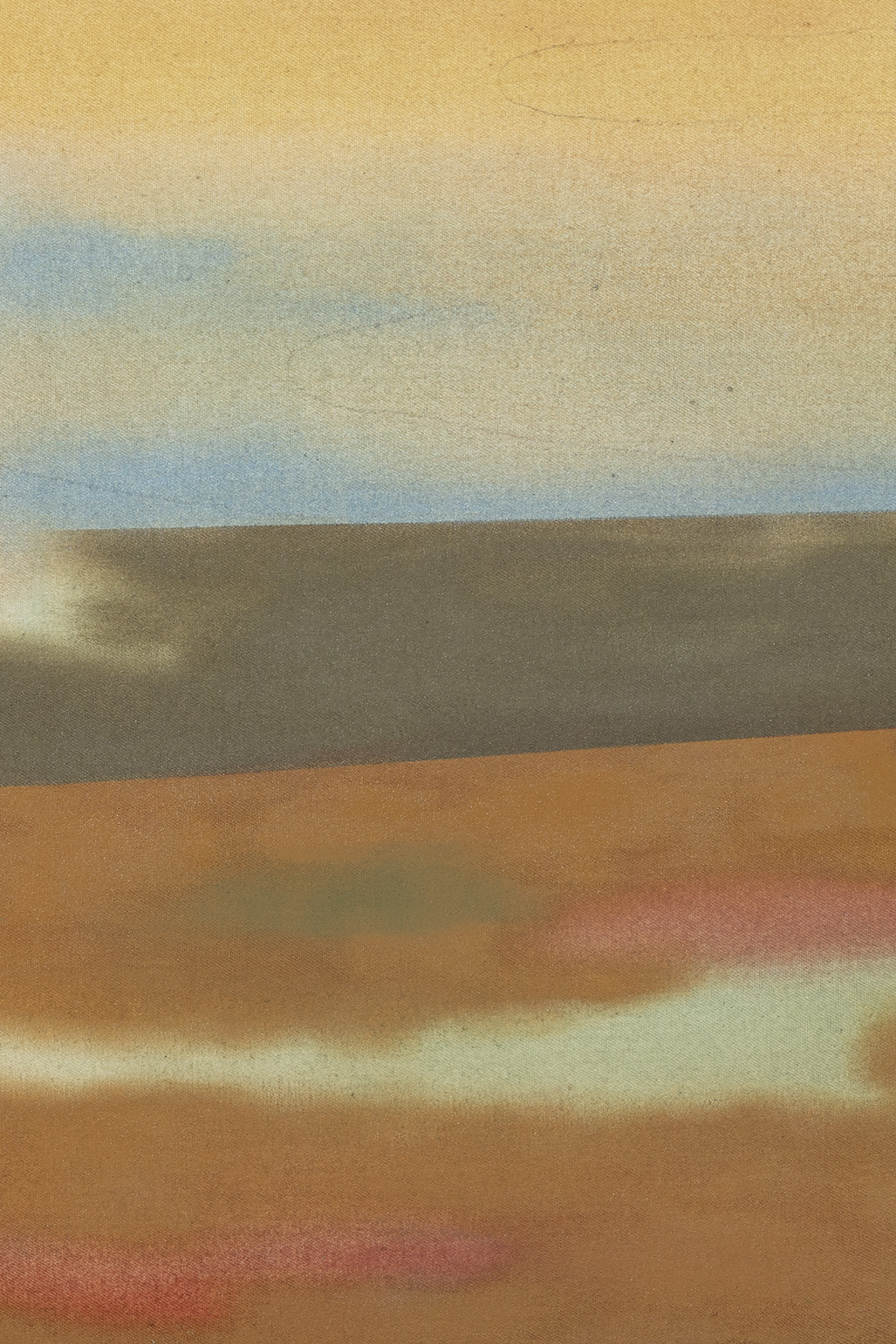

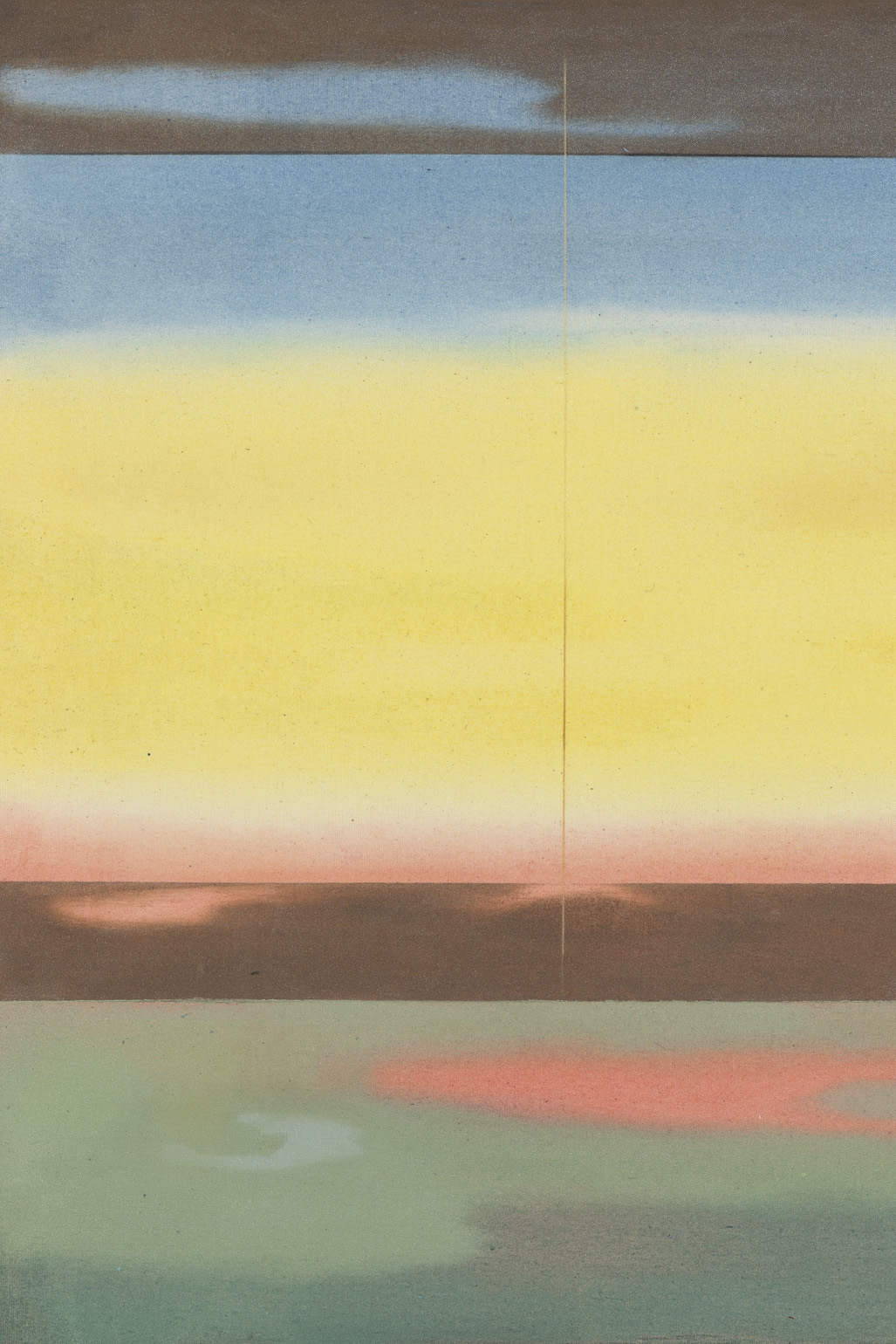

Annabell Häfner’s intimate paintings of architectural spaces emerge from hydrous washes of acrylic and delicate marks of chalk, rendering, draftsman-like, the more anonymous and liminal spaces of everyday life: the airport lounge, the corporate waiting room, or the hotel lobby. These are highly regulated spaces in which our sense of individualism begins to dissolve and render us anonymous, too; they are prone to induce boredom or impatience, but may also offer a brief respite, a moment of calm between contingent, consequential events.

a place to be, Häfner’s first solo exhibition in the United States, draws upon the anthropologist Marc Augé’s notion of “non-place,” the interstitial places – airports and hotels, metro stations and supermarkets – that have increasingly defined quotidian experience since the advent of modernity. Augé’s 1992 study from which the concept originates, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, coincided with the rise of the jet-set, exhibition-oriented, MacBook-toting artist, who found in Augé an apt description of the frenzied, paradoxically hyperconnected and isolated, lifestyle to which she submitted herself. But while such artists often reproduced the sleek sterility of non-places, what is novel and singular to Häfner is the affective register in which her works unfold: a narcotic, or even hypnagogic, dimension in which the dissociative potentialities of such sites come to the fore.

This dialectic is already apparent in the phrase “A Place to Be,” which suggests both a sort of distracted busyness (for instance, “can’t talk, I’ve got places to be”) as well as the more contemplative or existential associations conjured by the elemental verb “to be.” It’s in the shift from “non-place” to “place to be” where Häfner’s paintings locate their raison d'être, a shift from a possibly reductive, illustrative approach to their source material to a deeply beguiling form of experiential mapping.

The works’ emotive uses of color – broad striations of pale green, marigold, and cherry-red – function both as admirably as painterly abstraction as they do replicate the “continuous temporality” of long-distance travel, the simultaneous sunrise and sunset experienced by the redeye passenger. Another pleasurable sort of ambiguity emerges from compositions such as place to be 57, which might contain a Magrittian inversion of sky and ground, or otherwise generates a conflation of inside and outside, but then also puts us in mind of the glass panes and infinity pools synecdochally related to luxury real estate. It speaks to Häfner’s remarkable economy of means that the artist is able to generate such associations, or elsewhere render suggestions of furniture – side tables, sofas, communal benches – from a few planar elements and structuring lines of chalk, producing sparse reconstructions of these sites that register in the collective memory. Depicting expansive, even excessive, fields of space at an approachable scale, Häfner produces an oddly moving, haptic encounter. These works draw us closer, in toward unexpectedly affective compositions, as if headed somewhere in advance of nowhere.